To understand the situation of today’s Middle East, it’s necessary to review a century of history. Indeed one has to go back to the aftermath of World War I to see the establishment of a large proportion of the geopolitical data that explains the multiplicity of the entanglement of current conflicts. One thing is certain, if the great powers have long influenced the course of events in a decisive manner, regional and local players have asserted themselves increasingly throughout the century. After France’s and Great Britain’s domination during the inter-war years, both Cold War superpowers took over. After the fall of the Berlin Wall opened the phase of American omnipotence which was called into question after 11 September 2001. The globalisation era saw the regional powers widening their autonomy, their independence of action, their influence, and saw the rivalries between them exacerbate. Let’s try to see a little clearer.

Link to others 2 parts:

From one world war to another (1/3)

From the end of the Cold War to the aftermath of the “Arab Spring” (3/3)

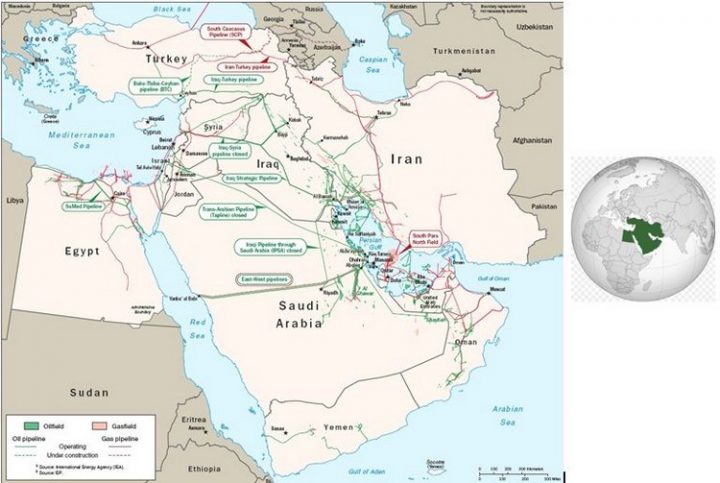

1945 saw the famous encounter between Roosevelt and Ibn Saud the Saudi ruler. It was the Quincy Agreement: US protection provided to the regime in return for a monopoly over Saudi oil. The traditional Franco-British rivalry, of which the Middle East was the theatre during the inter-war period, was substituted at the end of the Second World War by American-Soviet rivalry. It would mark the region for almost half a century. The Americans gradually took over the baton from the British. The French had to abandon Syria and Lebanon, partly under pressure from Arab nationalists and partly under the pressure of their Anglo-Saxon allies. Turkey joined NATO in 1952. Mossadegh, the Shah’s prime minister, tried to nationalise Iranian oil. He was overthrown in a coup orchestrated by the CIA. The Shah then owed his power to the Americans. The Baghdad pact, a kind of Middle-Eastern NATO, was created. It was the era of the Eisenhower doctrine, “containment”, which claimed to stem the influence of the USSR. It was clear that the Middle East, which contains the largest known hydrocarbon reserves, was a major issue of the Cold War. For the Western economies (USA, Europe, Japan), it must be remembered, it was the era of “peak-oil”. Low prices stimulated consumption, one of the pillars of economic growth in the post-war years.

The case of Israel, whose independence was proclaimed in 1948, was a special case since this state was the result of the partition of Palestine in November 1947, voted for by the General Assembly of the United Nations, at that time mainly composed of Western countries. Most Asian and African countries were indeed still under colonial tutelage. The refusal to share the Arab part of Palestine, supported by neighboring states, triggered the first Israeli-Arab war (1948-49) which ended in an Israeli victory. Three other wars (1956, 1967, 1973) ended with new victories for the Jewish state. In 1959 the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) was founded. It engaged in armed conflict against Israel, marked by guerilla action on its borders. In the aftermath of the 1967 war, the so-called “six-day war”, Israel occupied the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, that is, the Palestinian territories that remained Arab after the 1948-49 war. This was the beginning of what are known as the “Occupied Territories” in UN terminology. In 1982 the Israeli army invaded southern Lebanon to drive out PLO forces which had installed bases from where they could leed the guerrilla movement against Israel. The PLO was expelled, the Israeli occupation lasted 3 years. In the Occupied Territories of the West Bank and Gaza, a first Palestinian revolt, the Intifada, began in December 1987 and was broken by the occupier after several years of confrontation.

More generally, the confrontation with the Soviet camp directly impacted the entire region. Some Arab nationalist states rejecting Western interference approached Moscow. These were Syria, Egypt, and lastly Iraq. Nasserians and Baathists of pan-Arab, secular and socialist ideologies opposed the pro-Western monarchical regimes: those of the Gulf and that of Egypt overthrown in 1952, that of Iraq overthrown in 1958, that of Jordan, which resisted several attempted coup d’états. The Palestinian national movement, embodied by the PLO, of which Arafat took control in 1965, was also close to the countries of the East. The Middle East was thus on a level with the Cold War. The Peoples of the Middle East were confronted with censorship, a police state and repression everywhere.

In 1971, Great Britain granted independence to the small states of the southern shore of the Persian Gulf: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Members of OPEC (Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries established in 1960), they tended to align with the policy of the Saudi “big brother”. As petro-monarchies, they also benefitted from American protection and the solicitude of the West. The Shah of Iran became the regional policeman thanks to his oil and his army. Turkey, the south-western pillar of NATO, saw alternating civil and military regimes following coups d’états (1960, 1971, 1980) whenever the army considered that the country’s policy was moving too far from its Kemalist heritage.

1973 was a warning shot. Following the Yom Kippur war which saw Israel put in difficulty by the Arab armies before diverting the situation to its profit with American aid, the oil-producing countries decided the embargo and then the increase in crude oil prices. OPEC defended its interests. The Western economies were in crisis because of the renewed energy on which the growth of the post-war years was built, the famous “Trente Glorieuses”.

The shock of the Iranian revolution

A second oil shock, with the same consequences on Western economies as the first one, took place in 1979. This time, it was a consequence of a major political event. The Iranian revolution was indeed a real thunderclap. Before being reclaimed by the more conservative and authoritarian part of the Shiite clergy lined up behind the charismatic figure of the Ayatollah Khomeiny, this revolution was very popular and overthrew the Shah’s autocracy. It also reunited the traditional middle classes and the liberal bourgeoisie with the working classes and the Shiite clergy, or the far-left student movements and the communist party. In a matter of weeks, the administration and the army collapsed, refusing to serve any longer a regime discredited by its authoritarianism, its corruption, its megalomania and its alignment with the United States. The West was challenged as it had never been in the region. It then supported the Iraqi baathist regime of Saddam Hussein in an attempt to stem the revolutionary contagion: Iraq attacked Iran. The Gulf monarchies funded the Iraqis’ war effort. After a murderous war from 1980 to 1988, which claimed more than half a million deaths, an armistice was signed, without winners or losers.

Political Islam had meanwhile imposed itself as a major actor on the political, ideological and geopolitical scene of the Near and Middle East. Shiite political activism inspired by Tehran responded like an echo, half-rival, half-disciple to that of the Sunnites. The Sunnites Islamist movements, inspired by the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and Pakistan’s Jamat-i-Islami grew in the Arab and Muslim World. They challenged the order inherited from colonialism as much as the powers in place, whether republican or monarchical. They took over from the nationalist and Marxist currents that had lost their popularity following the military defeats against Israel, the relative economic failures of the regime in place, and finally, political repression. They took advantage of the Gulf monarchies’ money that had been flooding in since the enrichment following the increase in oil prices. The Saudi Wahhabis exported their interpretation of Islam wherever they could. But if the Islamists knew how to take advantage of the financial aid of the Gulf patrons, they nevertheless retained their critical attitude towards the alignment of the regimes on the West. In December 1979, the Soviet army intervened in Afghanistan to support the communist regime of Kabul which was prey to insurrection. Embroiled massively in the war against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the jihadists took an irreversible step. Funded by the Saudis, armed by the Americans, organised and formed by the Pakistanis, they contributed to the anti-Soviet jihad. It was nevertheless the Afghan “Mujahideen” who did most of the fighting. It was in this context that Al-Qaida was formed, an international organisation led by Bin Laden, the Saudi Islamist. It would acquire a sinister celebrity by perpetrating the attacks of 11 September 2001 against the Twin Towers of New York.

During the entire period the states of the region thus found themselves embroiled in major East-West confrontation. The Israeli-Arab conflict deviated in part from this configuration, given that Israel was more or less opposed to the hostility of all the Arab states of the region, whatever their allegiance, pro-American or pro-Soviet. The Iranian Islamic revolution revealed a new factor of upheaval: the politico-religious factor. The latter completely escaped the determinations arising from the Cold War. It prefigured the subsequent geopolitical evolutions as the next episode.

Translated from French by Julie Kieffer – Trommons.org