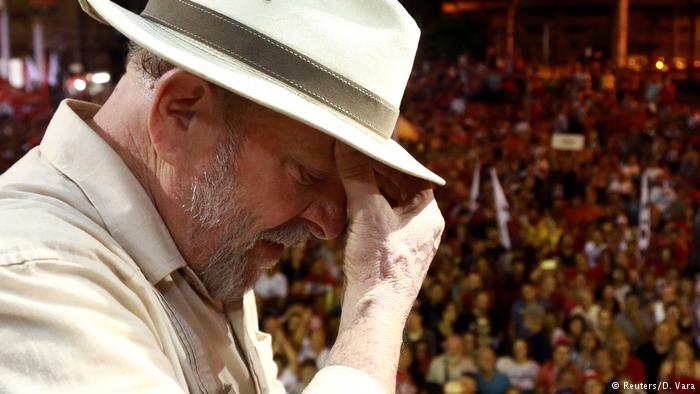

The decision of Brazil’s highest court of justice, rejecting Lula’s appeal against his 12-year sentence for corruption, is paving the way for his imprisonment. What has been resolved has unavoidable political implications for the next elections to be held in October of this year: it removes from the presidential race the person who leads the polls with 35% popular support and puts ahead someone who comes in second, Jair Bolsonaro, an ex-military, admirer of the dictatorship and defender of the application of torture, with nearly 20% of the voting expectations.

Lula has dominated the Brazilian political scene since thel times of the dictatorship. It was not easy for him to become president in 2003 because of the fear his party inspired, the Workers’ Party (PT). However, once in the presidency, despite his humble origins as a worker and trade unionist, he proved to be capable of governing under a moderate left-wing scheme, designing and implementing social programmes for the benefit of the most dispossessed sectors, which made it possible to significantly reduce the poverty that has always affected Brazil. When he ran for a second term in 2006, he won again thanks to popular recognition. He governed until 2010, when Dilma Rousseff, who was his chief of staff and of Lula’s own party, the PT, won the right to succeed him.

Meanwhile, corruption is spreading mercilessly, not only in Brazil, but on the continent and in the world. Corruption is globalized, in the case of Brazil, by the construction company Odebrecht. It splashes Lula and the entire Brazilian political and judicial class. Through a soft coup, through the courts, Rousseff was forced to leave the presidency and was replaced by the current President Temer. All this, by virtue of a trial initiated by those who are now in prison. The thief behind the judge. In the midst of this witch hunt, Lula is being run over. As if to say, whoever is free from sin, let him raise his hand.

At the same time, from the military barracks, there is the sound of sabers, and there is no shortage of people rubbing their hands waiting for their time. They can’t resist the temptation to get involved. This is how the commander in chief of the Army warns, via twitter: “I assure you that the Brazilian Army believes that it shares the desire of all citizens for good, for the repudiation of impunity and for respect for the Constitution, just as it remains attentive to its institutional missions”. Moments later, another general, by the same route, said: “I have the sword beside me, the saddle is equipped, the horse is ready and I await your orders!! Enthusiastic, another general of the military leadership said: “Commander! We’re in the same trench together.” This phrase is supplemented by a third general, who declares: “We are together, commander”. To top it off, shortly before, a general in the reserve had declared that if Lula was not sent to prison, “the duty of the Armed Forces is to restore order. Words bring out words.

Within the Armed Forces themselves, there are voices that invite moderation, expressing that it is not the case of all the Brazilian Armed Forces. This is what the head of aviation, who demands respect for the Constitution “without being so passionate as to put personal convictions above institutions” is saying. In addition, he is trying to pour cold water, saying, “Trying to impose our convictions or those of others is the last thing we need at this time.”

Faced with these declarations, the government is looking at the ceiling, relativising the messages sent from the highest military spheres and which involve the most blatant interventionism, forgetting that in a democracy military power must not interfere in the contingency and must subordinate itself to political power.

Many say that these is no time for coups. Unfortunately, during these decades of democratic transition that our countries have been experiencing, there have not been two essential changes with the required radicalism. One, that of the real subordination of military power to political power, since the latter has acted with a view to not stepping on toes in the military environment. And two, there is no sign of any repentance, institutional or personal, on the part of those who, at the time, when they had total power, engaged in practices of extermination. These two circumstances prevent us from ensuring that what happened in the Latin American militarist phase is not going to be repeated.

The polarization that Brazilian society is experiencing is the prelude to the coup d’état whose virulence will be unparalleled in the history of the continent. The losers will be the same who always lose, because those who have the handle are also the same who always have it.