Exclusion in Argentina: the case of Ezequiel Curaba

Once, before entering the José León Suarez prison (in Buenos Aires) to give a workshop, I was able to see how two children, almost teenagers, were burning a bunch of wires they had stolen from who knows where, in the middle of the street, under a motorway and inside a jar of peaches.

They were not on the side of the road, nor on the pavement. They were in the middle of the street, making fire, their fingers and faces covered in soot.

The image was shocking. It was extreme and promiscuous. There was no one who could contain these children, nor the fire they were burning, nor the tattered clothes they were wearing.

It was summer. It was hot. And there was no one to be seen around. The only thing that could be perceived was a constant feeling of abandonment. Of profound loneliness.

That particular scene was not seen by anyone. Or very few people saw it. The scene is not far removed from what can be found in other parts of the country, where the protagonists, among many other things, try to survive with whatever they can find: cardboard, soda cans, glass bottles, scraps of metal, and wood.

Without going any further, in Capital Federal they are paying at this moment (February 2024) $ 6,500 per kilo of copper, while in Florencio Varela they are paying $ 15,000.

How, amid misery, are the suffering bodies that suffer the anguish of not having bread every day not going to climb to their death?

With this information, Ezequiel took a gamble and tried to manipulate the underground electricity lines, with the awareness of having dug wells for the municipality of Rosario, and to distinguish in which places there was, with greater density, what he was urgently looking for copper.

Ezequiel’s burnt body went viral in a matter of minutes. Although you had to look at it several times to distinguish which nationality it belonged to. The scene seemed to emulate the iconic image of the Vietnamese girl escaping naked from the US attack with napalm bombs.

Ezekiel’s scene is clear but at the same time confusing. Clear because it is clear what is happening: a young man completely burnt, his skin black and pink. Staggering. Agonizing. Confusing because you don’t know who he is, it could be anyone else, from any city in Latin America. Ezequiel represents a witness case of other cases that end their lives wrapped in the melted plastic of the poles without light.

“In Villa 31, the kids cut the high-voltage cables with a tramontine,” a friend who works there confesses.

The copper extractors hang from a cable, juggling in the air, with the aggravating factor of being hungry, dizzy, and clumsy because they haven’t eaten, and overdone with illusions and impossibilities.

They play Russian roulette, or rather the most filthy capitalism plays with them as a bullet, a rope around their necks, a bomb to defuse. The hoarding market makes them parade towards the horror, without any kind of protection, without any kind of shelter, without any kind of reparation.

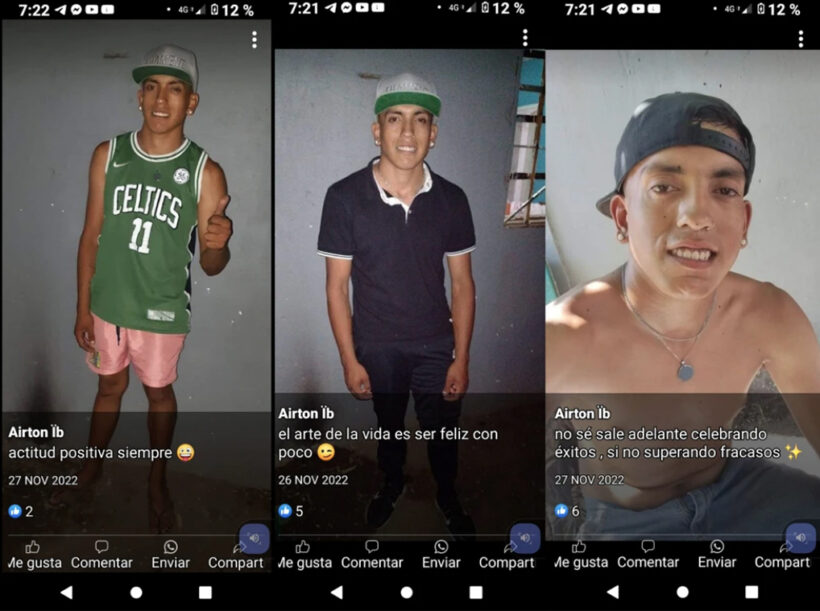

Ezequiel tried to study, but in the pandemic, he was left out of the education system. Ezequiel tried to have a decent roof over his head for himself and his brother, but a few months ago, amid the advance of the ultra-right in Argentina, he was left on the street. Ezequiel tried to earn a living in the underground of privilege and met his death. Ezequiel was just starting in life, or rather, at his young age he was already carrying several beginnings on his back.

Ezequiel is one of those kind of neighborhood kids who spend part of his life stumbling, making excuses over and over again, so as not to resign himself, so as not to fall into the abyss, so as not to shove an iron down anyone’s throat.

“One day, for children’s day, in fourth grade, Ezequiel asked me for a towel, because he was tired of drying his face with the same dirty clothes he used to take off”, Gaby, one of his primary school teachers, told me over the phone.

Yesterday it was cardboard and copper, tomorrow maybe he will clean a yard, later he will sell food on the street. We will never know, because Ezequiel is no more. His vital organs stopped working after the electric shock he received from the cables he was planning to sell.

In whose head is there room for so much fruitless ingenuity? In whose heart is there room for so much despair?

As in the film “The Turtles Also Fly”, which portrays the life of a group of children in a refugee camp, victims of the Iraq war (2003), who survive by disarming mines, Ezequiel portrayed their daring lives, between juggling, epic dexterity and the adrenaline of a latent death. The most lacerating abyss that an individualistic society can build between dignity and the miserable immolation of human desire.

Do we lynch him or help him? Where will a society that is far more willing to chew on the wire than to give a towel to dry the sooty faces that swarm the nation’s dark suburbs fire its response?

In what war are the kids who try to dismantle, with bare hands, the high-tension wires that light up the homes of the rest of society?

What if Ezequiel was trying to connect clandestinely to electricity, did he also deserve society’s repudiation, verbal lynching, and physical stoning?

Finally, it is a question of extracting the part for the whole. It is the man from Villa Crespo blowing up a million-peso glass door to extract just a piece of metal embedded in the lock. But it is also the trawling that takes place on the Valdivian coast of Chile, taking even the local flora for a few species of fish. It is the fracking of the Upper Valley, sucking up water tables, contaminating the soil, killing animals, and causing the migration of the population to extract every last drop of energy from the earth. It is offshore fracking that prevents even trawling from developing. It is the part for the whole. It is Ezequiel stretching out his arm to see if some of the energy that feeds the whole city of Buenos Aires will soak him too, once and for all, to get out of where he is, to stop walking on the edge of misery. It is the construction of the “good consumer citizen”, who, to sustain his outfits, has to be exploited by 100 different people in 10 different parts of the world. It is the daily injustice of seeing, between one crime and another (counting the gap between each of them), how it is only the anonymous and attainable individuals who feel, in their faces and bodies, the social outburst of the indignant.

It is a question of understanding the metaphor that this type of neoliberal and neo-extractive society in which we live is proposing to us: to achieve the privilege of a few, we must set ourselves on fire, put our lives at risk, and sacrifice our will. To corrupt us. To break us into a thousand pieces. Even enduring, as if it were a “deserved torture”, that the public, who watch us indignantly, do not help us. On the contrary! Seeing how they throw more earth and petrol at us. Stones. Bullets. Their disproportionate and intolerant repudiation.