The sad events that took the lives of a taxi driver and a bus driver in the city of Rosario are well-known throughout the country. These events are being investigated by the courts, while the government, in a show of its “iron fist”, has sent troops from the army, the gendarmerie, the prefecture, and the federal police to the poor neighborhoods.

The widespread coverage of these unfortunate events comes on top of the daily, continuous, and omnipresent coverage of crime and violence by the hegemonic media. This agenda reinforces a one-sided scenario that keeps the population in a state of permanent tension, mistrust, and fear.

By focusing on specific incidents and occasional perpetrators, attention is diverted from the real perpetrators of these crimes and offenses, namely those who, through emotional anesthesia and cynicism, promote or accept the systematic exclusion of millions of young people from real opportunities for livelihood and human progress.

In a study, Polish researcher Piotr Chomczyński argues for the idea of the “collective trajectory”, according to which drug recruiters focus on a person’s social circumstances and background to persuade them to join a gang. “I was struck by how many people in marginalized areas believe they have very few options in their lives. Continuous exposure to organized crime over a long period changes many people’s perspectives and they do not actively seek other options. This mentality is very widespread and is passed on from one generation to the next”[1].

Another side of the same coin, or rather the lack of it, is the increase in forced migration due to misery or violence, combined with the effects of climatic phenomena such as droughts and hurricanes.

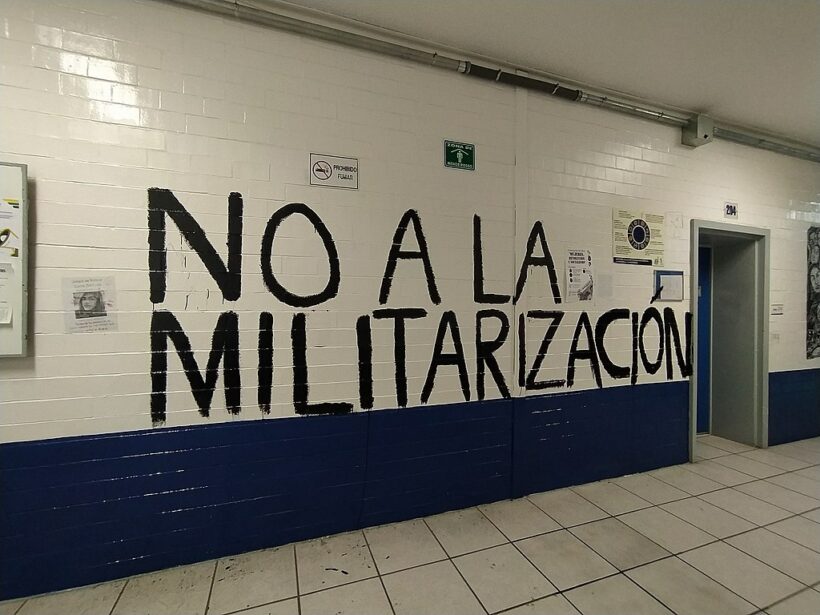

What these media do not mention, and most people do not know, is that the widespread installation of criminal violence in the region, with its correlation of militarization and social control, is part of a plan.

The real criminal plan

The confusion between police and military functions began in Colombia and continues in Mexico and Central America, as Horacio Verbitsky points out in an article for Página 12[2]. “It is encouraged by the United States, which provides training, directly or through Colombia, always warning that it is an exception while improving police training. The result is disastrous: inefficiency in fighting crime and serious violations of human rights,” he adds.

In addition, the US has allocated huge sums of money to finance militarization, which entails the purchase of weapons and equipment that, depending on the level of corruption in each place, end up swelling the arsenals of the very criminal groups they claim to be fighting.

The strategy referred to by the journalist, whose main antecedents are Plan Colombia and the Merida Initiative, has now entered a new phase with the current Southern Command project, included in the 2017-2027 Theatre Strategy document presented by Kurt W. Tidd, the predecessor of the current commander Laura Richardson, a good example of the “pinkwashing” of the US deep state, like Obama’s “black washing” in his time.

“This plan is our model for defending the southern gateways of the Americas to its interior and promotes regional security by reducing threats from trans-regional and transnational illicit networks, responding rapidly to any type of crisis (natural or human), and building relationships to address global challenges,” the document reads.

According to the text, SOUTHCOM’s strategy is to “cultivate a network of allies and partners and conduct our activities as part of a comprehensive effort through this integrated network of the Joint Force, intergovernmental and multinational agencies, and non-governmental organizations”.

It is significant to note that this “network of allies” usually relies on right-wing governments to implement its plans, which are otherwise hindered when popular governments, determined to increase sovereignty and peace, take power.

The process of military intervention – usually called “security cooperation” – is complemented by the training of prosecutors and judges in US Justice Department courses, who then collaborate with the inhibition of progressive candidates, the insertion of NGOs and humanitarian aid programs run by soft-front agencies such as USAID, intelligence services, business chambers, academic groups, foundations and, of course, the actions of embassies in each country.

This combination of forces makes it possible to achieve objectives that would be difficult to achieve by military force alone, given the relatively recent memory of the atrocities committed in the region by the dictatorships of the last century.

However the insecurity caused by criminal violence and the widespread perception of its generalization among the population, encouraged by the media, gradually leads to a public outcry, which, if this is not enough, ends in a call for local or foreign armed intervention. This completes the cycle of destruction and social control, adding fuel to the fire.

Broadening the focus

Latin America and the Caribbean still have a strong demographic contribution from the younger generations, unlike other regions with a negative replacement rate. However, the production matrix, systemic financialization, and economic concentration make it very difficult to achieve adequate social absorption that would allow these cohorts to live without shocks or shortages.

On the contrary, the vast “reserve army” – according to Marx, the part of the population that is surplus to the needs of capital accumulation – that used to serve as cannon fodder in wars is now forced to enlist as workers without labor rights in digital service companies, to try to find better opportunities abroad, or to join the criminal drug gangs and other thriving underground forms of survival.

This explains the security problems faced by almost all the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, which are still far from the desired zone of internal peace. Several of these countries, such as El Salvador, Ecuador, Peru, Haiti, and Argentina, are opting for deadly alliances with the war machine of the United States of America, which, far from offering solutions, will bring, beyond the official discourse, an increase in insecurity and public debt.

The more general picture is given by the struggle for world economic and technological supremacy in a closed capitalist preserve of limited growth. Instead of understanding the value of cooperation, the stubborn logic seeks to continue competition at all costs to defeat the rival.

Thus, in the face of the imposing new revolution that has made China a world economic and scientific power in less than fifty years – from 1978 to the present day – the United States, the heir and successor of European colonialism, faithful to its tradition of war, is once again dragging the world into a global confrontation.

Trapped by increasing internal entropy and despite maintaining a strong global military and diplomatic presence, the USA has lost ground in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, while retaining a strong influence on European territory through NATO expansion and attempting to create anti-Chinese or anti-Russian alliances in various areas.

As for Latin America and the Caribbean, its geographical proximity to North America and its vast reserves of raw materials makes it a coveted player in this struggle, which is currently tilted in favor of the adversary, which has been able to promote itself as a regional partner through its purchasing power, investment strength and source of finance. Moreover, this partnership has been strengthened by China’s lack of interest in directly interfering in Latin America’s internal politics, while reserving the right not to interfere in matters it considers relevant to itself, such as Taiwan or the secessionist or religious tensions in Tibet and Xinjiang.

In this context, the soft invasion of the US apparatus in the region under the pretext of security cooperation, as is happening today in Ecuador, Peru, Haiti, and Guyana, and most likely in the short term in Costa Rica, Argentina, and even Guatemala, is reminiscent of the same practices, now two hundred years old, developed since the application of the Monroe Doctrine. These are practices that demand alignment and submission in the global struggle and foreshadow black clouds on the horizon for our people.

There are no dead ends

From every labyrinth, you escape from the top, called one of his poems Rodolfo Marechal in his major work “Adán Buenosayres”. However, with the greatest respect for the poet, “finding the way out” – another colloquial miracle – to the current complex situation could also mean doing it “from below”, meaning the need to rebuild the lost unity of the popular forces to avoid major catastrophes.

Such a slogan may sound in some ears like a nostalgic remnant of old struggles, so it is worth elaborating on its content. What we are talking about here is a convergence of diversities under the banner of common goals, without seeking uniformity or internal hegemonies, yes, a remnant of other eras.

Its unity in welcoming diversity, this articulation of particular struggles towards the utopia of collective human development, is the way to tackle today’s struggle against the disintegration and social cruelty that right-wing fundamentalism is fomenting today.

It is legitimate to think beyond the political conjuncture, which must be confronted with grassroots work, sincere dialogue, and the integration of differences. The suggestion of “going inwards out of the labyrinth” can also be useful, pointing to the possibility of a simultaneous task of political accumulation, together with the revision and modification in each person of those stagnant elements that, far from helping to banish social violence, on the contrary, increase it.

The human being does not have a delimited or determined nature and is not even an entity whose possibilities can be taken for granted. In this sense, the progressive eradication of individual and collective violence could be a great cultural conquest and a great gateway to the future. In short, a way out of the current impasse in which we find ourselves, with greater historical depth.

[1] Collective experience favours cartel recruitment in Mexico. InSightCrime. May 2023. https://insightcrime.org/es/noticias/experiencias-colectivas-favorece-reclutamiento-carteles-mexico/

[2] http://www.vecinosenconflicto.com/2013/09/america-latina-el-comando-sur-de.html