Richard Nossar and Carlos Torres Rotondo, authors of ” We Will Remain Until the Very End”, immerse us in the vibrant Peruvian hardcore scene between 1985 and 1989. From self-management to internal social tensions, the protagonists reveal the foundations of a scene that endures, transcending time with values of solidarity and authenticity.

By Sol Pozzi-Escot

Why focus on the period 1985-1989?

RICHARD NOSSAR Why because it was the initiation period and the stage at which we approached the movement.

CARLOS TORRES ROTONDO The same. Because I lived it. However, it’s not a closed period. There are still bands coming out that make hardcore within a broad spectrum that goes from visceral to melodic, and that started there. The echoes persist, the presence in today’s scene.

What conditions at the time favoured the emergence of the bands and the hardcore scene?

RICHARD NOSSAR Hardcore was born in the United States in the early 1980s in the midst of a change of government that represented a threat to freedom of expression and civil rights. In Peru, it appeared during one of the darkest cycles in our history. A time marked by political violence, inflation and unrest.

Although the first hardcore records arrived in Lima almost parallel to their release abroad, it took several years for the first bands to venture into the sub-genre.

CARLOS TORRES ROTONDO The context was against them, but enthusiasm won out and they did what they did. It was built despite the national crisis and the rarefied climate within the underground scene itself, which replicated in a small way the anomie of the time.

KAOS GENERAL at Alejandro Peña’s house. From left to right: Coco La Rosa, Armando Millán, Ricardo Salazar and Alejandro Peña. Photo: Rosa Peña

KAOS GENERAL at Alejandro Peña’s house. From left to right: Coco La Rosa, Armando Millán, Ricardo Salazar and Alejandro Peña. Photo: Rosa Peña

Why was it important for there to be a whole scene, a movement, around music and bands?

CARLOS TORRES ROTONDO. We all liked music and took the initiative in this regard. There was almost no audience in the pure sense. We were all prosumers. Whoever didn’t make a band, published a fanzine, organised a concert, or stuck up a poster. That’s how punk-derived scenes work.

In the book, you mention many fanzines of the time, what role did they play in the hardcore dynamic?

RICHARD NOSSAR Fanzines were handmade publications that constituted the written press of the scene. They were the main means of musical and ideological dissemination and were generally distributed at concerts.

As they depended on the time and disinterested effort of their creators (mostly teenagers), they did not manage to survive for more than a few years.

CARLOS TORRES ROTONDO Underlying this type of self-managed publishing was a vision of the world, a shared ideal of what culture and community should be like. The fanzines were like electrical stimuli within a neural network: a generator of communication that brought us together as a scene and enrolled us in the international hardcore circuit.

The rivalries and enmities that were generated are also touched upon. How do you explain these divisions with a social background within the scene?

RICHARD NOSSAR With a historical background like ours, it’s easy to understand that such a schism would come sooner rather than later, especially considering that hardcore is a counter-cultural and consciousness-raising movement. The more personal rivalries and feuds were a matter of investigation, as when Carlos and I arrived on the scene, it was already fragmented.

I never had any problems with the subways.

CARLOS TORRES ROTONDO At the root of it all is the very complex problem of Peru, of all those bloodstains that have not yet healed, it is true, but we must also see them as concrete and personal cases of chibolos huevones. Some have evolved, others have not even considered it. It is very easy to stereotype others and not think about what people are really like. And yet, beyond all that shit, unlearning what a society as perverse as the Peruvian one has taught you is the great conquest of many of those who built themselves as individuals within spaces like the hardcore scene or underground rock.

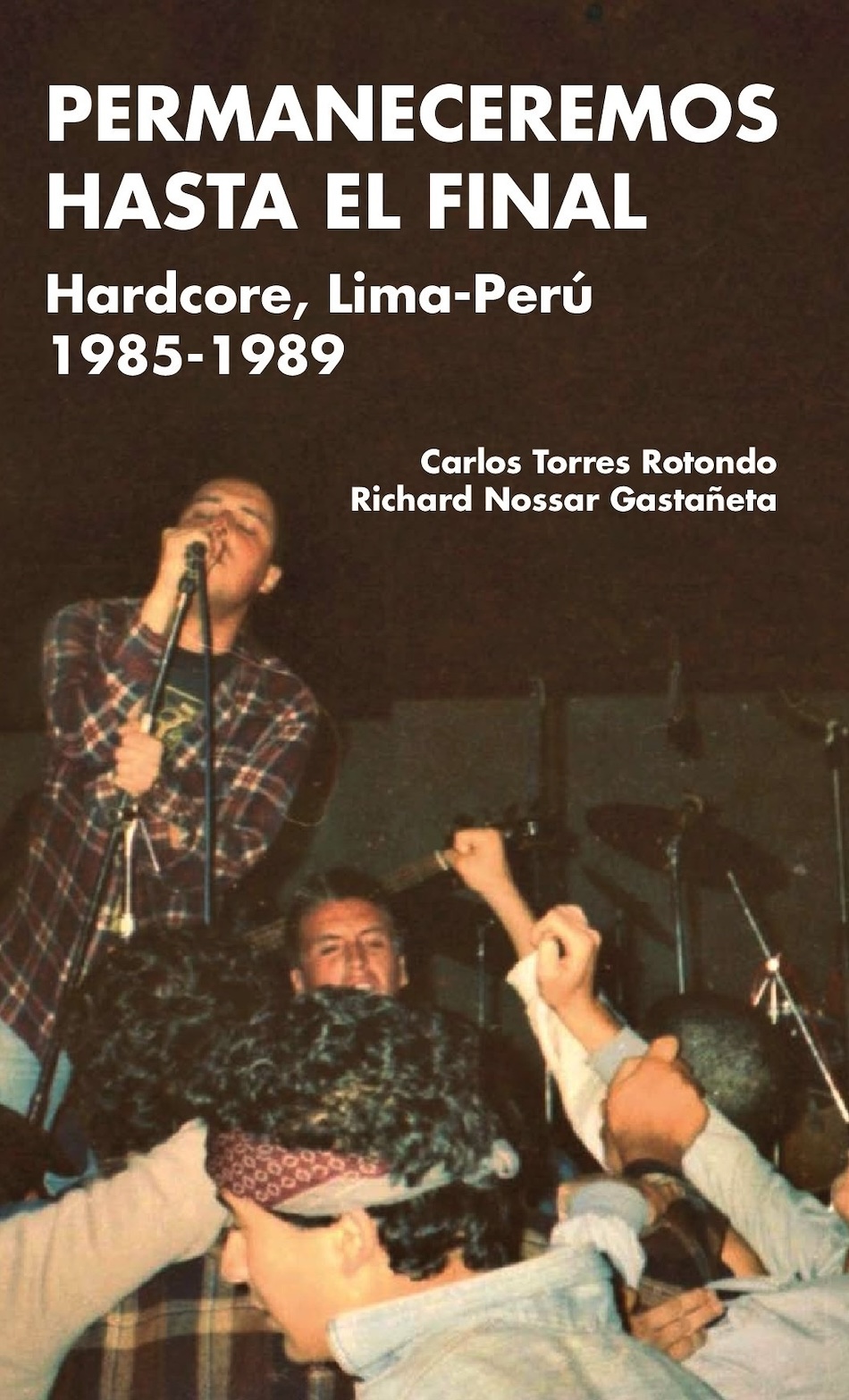

Cover of Permaneceremos hasta el no end. Silvio Ferroggiaro with ATAQUE FRONTAL at Los Reyes Rojos school. Photo: Coco La Rosa

Cover of Permaneceremos hasta el no end. Silvio Ferroggiaro with ATAQUE FRONTAL at Los Reyes Rojos school. Photo: Coco La Rosa

What role did hardcore have in the search for an individual identity for those who were part of this movement?

CARLOS TORRES ROTONDO The classic spaces of socialisation of a middle-class adolescent in Lima (especially school) inevitably push him too lethargic consciousness. I always had an uncomfortable relationship with that form of normality and hardcore made me meet people who thought like me.

On the other hand, on a social level, did hardcore contain some kind of political agenda or was it on a separate path to what was understood as political activity per se?

CARLOS TORRES ROTONDO Beyond indignation at social inequalities, only artistic movements subordinated to political organisations consider the effective seizure of power. Ours was more about individual change.

G-3 at La Jato Hardcore. From left to right: Gonzalo Farfán and Gabriel Bellido. Photo: Richard Nossar

The book also mentions the reduced participation or presence of women in the scene. How do you understand this?

RICHARD NOSSAR I suppose it took a while for the style to awaken the interest of the female audience. The funny thing, the first women to show up were extreme metal fans, a sub-genre that coexisted with hardcore during the twilight of the 1980s.

How do the ideals espoused in this era (1985-1989) and embodied in the musicians and figures described in the book hold today?

RICHARD NOSSAR Because they are timeless. Hardcore will be values and actions that appeal to solidarity and self-management, rejecting the marginalisation imposed and encouraged by the dominant system.

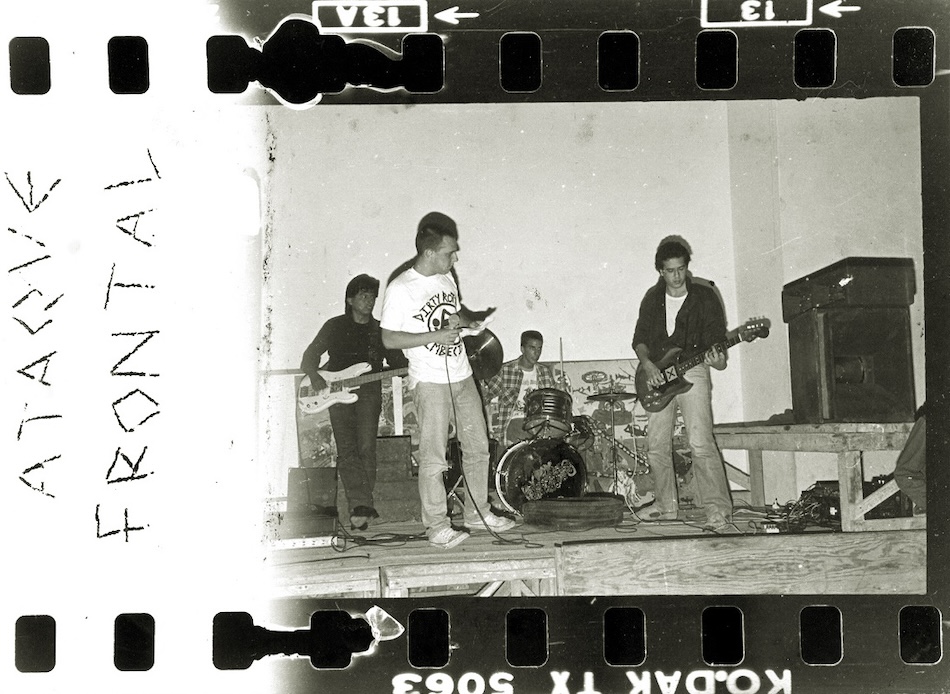

FRONTAL ATTACK at Los Reyes Rojos school. From left to right: Raúl Montañez, Silvio Ferroggiaro, Fernando Boggio and José Eduardo Matute. Photo: Dalmacia Ruiz Rosas Samohod

FRONTAL ATTACK at Los Reyes Rojos school. From left to right: Raúl Montañez, Silvio Ferroggiaro, Fernando Boggio and José Eduardo Matute. Photo: Dalmacia Ruiz Rosas Samohod