Talking today with a grandmother who has observed education for the last 60 years, first as a pupil, then as a mother and now as a grandmother, she was telling me that what remains unchanged is the definition of a good student: quiet, obedient, orderly and who doesn’t ask her difficult questions in the classroom. If she learns and does well in tests and exams, so much the better; if she doesn’t learn, it doesn’t matter.

It is because of this way of evaluating children and young people that education is stagnating. The role of teachers has remained the same for more than a century: an adult who has (or should have) the knowledge and transmits it in a boring way to his or her students. If the mission statement is to develop critical thinking in students, they are not taught to ask questions and, even worse, they are made uncomfortable when they are very curious and inquisitive.

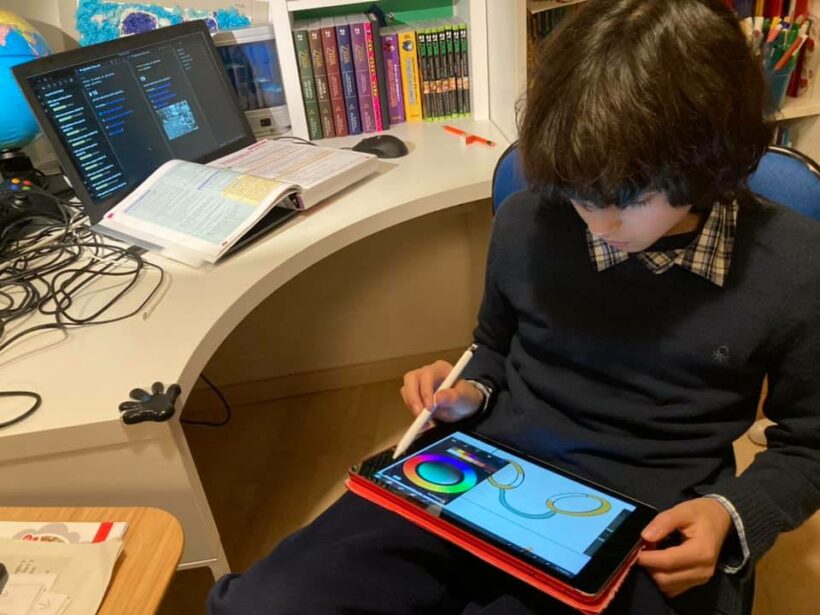

The introduction of information technology (IT) in the classroom is still under-utilised because its use is only to reinforce the educational paradigm mentioned above.

The full potential of IT is viewed with suspicion when it threatens the status quo and pushes the system out of the comfort zone. It is easier to criticise the irruption of new technologies, to see all sorts of threats to the cognitive and emotional development of children and young people. I am reminded of my university days when my engineering professors said that using an electronic calculator would make us foolish.

Today the focus is on artificial intelligence (AI) and it has become the villain of IT.

It is true what critics of AI say that AI makes mistakes because it gathers information from the internet, where not everything published is true or correct; they also point out that students do not learn when they look to AI for responses and become mere copiers. These are valid arguments only when looking at AI in the light of the current educational model where teachers ask the questions and students come back with the responses.

Mass access to AI applications will have an unpredictable effect on education just as electronic calculators and computers did 50 years ago. It will force teaching teams to develop critical thinking in their students and teach them to ask intelligent and well-structured questions in order to obtain responses of equal quality. Otherwise, as the popular saying goes, a stupid question gets an even stupider response.

The process of change will also have to change the focus of pedagogical incentives. In addition to learning to ask questions, it will be necessary to encourage children and young people to dare to ask them in the classroom and for adults to internalise the reality that they do not have all the knowledge and thus, together with their students, they will seek the responses, which is an efficient learning method.