There are books that leave their mark on people and beyond, on collectives, countries and different generations. We are talking about the Popol Vuh or Popol Wuj – the closest to the K’iché orthography – and with a universal meaning like few others.

Religion, mythology, history and astrology place this work at the pinnacle of Mayan and universal literature, without any discussion whatsoever.

Among its various names, it is known as the “Book of the Council”, “Book of the Community”, “Sacred Book”, “Book of the Mat” and even “Mayan Bible”, the truth is that many enigmas surrounding its origins remain to be discovered today.

To its great aesthetic value, scholars add that of being a great window through which one can glimpse the cosmogony of the K’iché people before the arrival of the Spaniards on American soil.

Its content corroborates data found in pottery, stelae and even in the monumental monoliths that they left us as a legacy, some of which remain deep in the vegetation of the Guatemalan jungle.

HISTORY

It tells the Mayan creation story, the tales of the Hero Twins and the Quiché genealogies and land rights.

HOW DOES IT SAY IT?

Brasseur calls it Popol Vuh; Adrián Inés Chávez, Pop Wuj, and Enrique Sam Colop, Popol Wuj.

WORD

Although apparently popol does not exist in the Mayan languages, the word is used by the indigenous Yucatecans, and it means council or meeting.

THE SACRED BOOK OF THE MAYAS

NAME

It was given its name by the French priest Charles Etienne Brasseur de Bourbourg in 1861.

Popol-Vuh

As far as influences are concerned, the presence of the Popol Wuj is undeniable in national literature, but also in that of Central American authors.

The Guatemalan Nobel Prize winner Miguel Ángel Asturias would not have created his masterpiece, Hombres de maíz, if the ancient codex had not existed as an antecedent.

Asturias returned to the origins, but not to the Western myth (Ulysses, Prometheus, the Bible), but to the pre-Columbian myth, to the primordial Latin American being, the corn man.

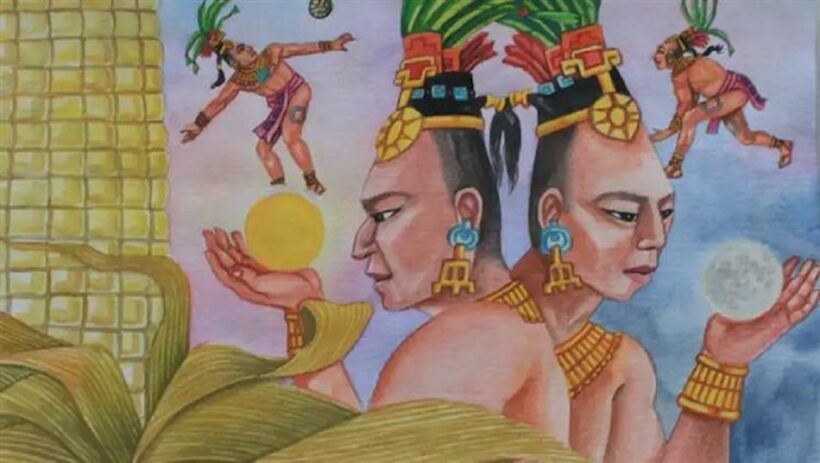

In general terms, the story narrated in the original 16th century manuscript has three parts: one describing the creation and origin of the corn people; another about a time before that process, with the mythical adventures of the twin gods Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué in the Mayan underworld; and the last with the lineage of the K’iché people up to the last kings killed by the Spanish army.

To understand the great importance of the Popol Wuj, researchers point out that it speaks of a cosmogony and a cosmovision. The former refers to the way in which a people explain the origin of the universe and everything around them, while the latter responds to the way in which they see the world and how they explain it through stories.

It also reflects unique aspects of the territory from which it was written, as well as spiritual, ideological and artistic expressions. Best of all, its values live on in Mayan communities because they are contained in the stories that grandparents still tell.

AN EVENTFUL HISTORY

Along with the conquistadors came several priests who, in their eagerness to convert the indigenous people to the “true religion”, destroyed everything that had any connection to pre-Columbian religions: temples, gods and entire bookshops of codices.

Studies indicate that the Popol Wuj, as we know it, was written shortly after the Conquest in the K’iché language with the aid of the Spanish alphabet by one or more Christianised Indians, possibly members of the defeated royalty.

Some identify one of the possible authors as an indigenous man called Diego Reinoso, but most agree that it is of unknown origin or a collective author through oral tradition.

Where there is agreement is in the approximate date of its writing, between 1554 and 1558, until almost two centuries after the version that transcended to the present day came to light, when the priest Francisco Ximénez had the original in verse form and translated it into Spanish prose.

From this Dominican manuscript, versions were published in different countries and languages during the following centuries.

A POPOL VUH FOR CHILDREN

Scholars who knew Ximénez’s manuscript say that it is not an easy book to read because of the density of its language and figures, especially for children.

This is precisely what the pen of Francisco Morales Santos had in mind, who had in Guillermo Grajeda’s illustrations the ideal way to meet the challenge of transferring the stories, myths and legends of the K’iché people to new generations.

As the author recalled in an interview with Diario de Centroamérica, the creative process was marked by the responsibility of bringing the primordial text of our literature to children and, in addition, facilitating their encounter with the national editions of Adrián Recinos, Sam Colop and Adrián Inés Chávez, among others.

Morales will be preserving the ancestral history to capture it in the most reliable way with a good use of language, he said in the interview. “We must always have in mind that childhood is a state, not a limitation to understanding,” he said.

The work of the 1998 National Literature Prize winner was complemented by the illustrations of Grajeda (1918-1995), one of the most important names in Guatemalan visual arts, who created expressive drawings inspired by characters and adventures from the sacred book, ready to colour in and unleash the creativity of readers.

“The fusion of Guatemalan talent makes the approach to the work with enthusiasm and curiosity,” said editor Irene Piedrasanta at the presentation of the book under her publishing imprint in 2019.

WITH THE PASSAGE OF TIME

As one of the most relevant documents of Mayan culture, the Popol Wuj stands the test of time and many enigmas still remain. Its transcendence ranges from the historical, cultural, anthropological to the literary, beyond the values of the original writing.

As discoveries have progressed, the existence of many real places linked to its existence has been proven, and the interest transcends within the virtual world itself: just google Popol Vuh in the famous search engine and 66,400 results appear.

But what makes this book so special?

Many mention its sacred status; however, Mayan-Kaqchikel anthropologist Aura Cumes disagrees, because in her opinion, giving it that quality would make it a book related to fundamentalism, which would point to an “absolute truth” or immovable truth of things.

She suggests seeing it as a historical book that compiles a worldview – or as many calls it cosmovision – of the Mayan peoples, as it was one of the few that managed to be saved.

For the Mayan-K’iché linguist, lawyer and poet San Colop, its importance lies in its register of the mythology and history of the Mayan people until the colonisation of the Spanish in the 15th century.

Other aspects point to the fact that it shows a vision contrary to that inherited from the process of conquest itself, based on a single race, a single time and a single god. The book speaks of the dual, “even” or “poly” world, whose creation was assumed by multiple couples headed by the sky and the earth together with all that exists.

The anthropologist Lina Barrios argues for natural diversity: 92 Guatemalan species are mentioned, 41 flora and 51 fauna, and the role of women is also relevant.

The energies are feminine and complementary, and midwives, governors and warriors are mentioned.

Perhaps the most integrating vision is that of Mariela Tax, poet and popular educator, who considers that within the Popol Wuj, life itself is perceived in the conjugation of the elements, nature and wisdom as part of a whole, but also of the structures that are shaped, constructed and reconstructed throughout history.

In the midst of the poetic, the words bring a sensitivity to the diversity of life. At the same time as they serve as a guide during the narrative, they also allow for a deepening, he argues.

Its relevance for Guatemalans was endorsed on 30 May 1972, when it was declared a National Book. On 27 August 2012, the Ministry of Culture and Sports inscribed it as Intangible Cultural Heritage of the Nation.

In August 2018, nationals and foreigners had the great opportunity to see up close a facsimile of the Popol Wuj written by Ximénez in the museum that bears the name of the K’iché text in homage to its 40th anniversary of trajectory in favour of exhibiting the best of pre-Columbian culture.

The piece was the centrepiece of that year’s temporary exhibition, along with a dozen archaeological objects and 32 of Guillermo Grajeda’s drawings.

Its director, Rossanna Valls, reminds Prensa Latina of the fidelity of the duplicate with details such as the edges of the pages or the marks that the ink leaves on the back of the pages over time.

Although another edition had previously been delivered to the indigenous municipality of Chichicastenango, access to it was limited for the general public.

The question arises in everyone’s mind: What does the text that is closest to the original really look like?… and to be able to see it up close and have it permanently in the museum is a dream come true, said Valls.