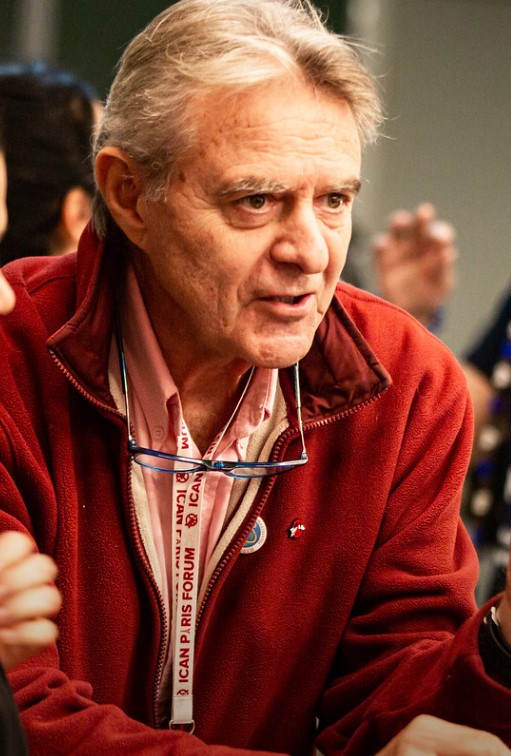

Rafael de la Rubia welcomes us into his home and we settle into a room full of books. On the table is a huge illustrated book about the World March for Peace and Nonviolence that was organised in 2010 and which, after a long career across the planet, ended at the foot of Aconcagua, in the Andes, in the historic park of universalist humanism in Punta de Vacas. That march, supported by a wide range of people – by scientists, artists, politicians, representatives of hundreds of cultures – and which was received and personally supported by presidents of different countries, is today more remembered than ever. Afterwards, other marches have taken place, including regional marches in Latin America, and it is clear to no one that today more than ever it is necessary to unfurl this universal flag, especially in Europe. The march of Leopard tanks or invading troops should be opposed by a huge march of good people demanding an immediate end to the conflict, to all conflicts. The twofold interest in interviewing this old humanist friend is not only because of his militancy for peace and nonviolence, but also because of his personal knowledge of Russia and his affection and respect for the Russian people, a people of whom a monstrous and distorted image is being projected at this moment…

At the moment, there are several calls for peace and nonviolence in the neighbourhood, from film shows to spaces of convergence between cultures. The “No to war” warning that, in addition to Putin’s warmongering actions, NATO’s actions have not been or are not being innocent either.

P. It seems, Rafa, that you are still going on with the world marches. After that huge deployment in 2010, we know that after that there have been others…

R. Yes, we did one and after that we didn’t know if we would do another one. It wasn’t planned and, seven years after the first one, I still had that “come come” and we said to ourselves: “Let’s do some preliminary tests”. We wanted to know if there was enough muscle to do a second march. We did a Central American march, as a test in 2017, and from there came the idea of doing a South American march and we did that too. In some countries like Peru and Chile, more cities had participated than in the first World March.

P. That first march was tremendous. It was something big, many presidents of governments supported it, especially from Latin America, and you didn’t avoid conflict zones…

R. Yes, we moved through conflict zones, on the border between North and South Korea. We were also in negotiations with the Moroccan government and the Algerian government to see if we could open a symbolic crossing, but they didn’t want us to. We were in Tijuana, on the border between Mexico and the United States, and then on borders that are not very well known and which we reinforced with the second World March. We were on the border between Honduras and El Salvador, which has the particularity of having fought the shortest and fastest war in history. It was a war that lasted three days and that, as a result of a conflict in the World Cup in Mexico, each of the governments had internal problems and it was good for them to create this war. It had six thousand dead and three hundred thousand displaced people. During the second World March, we held an event at the border, mobilising people from universities in Honduras and El Salvador. In the free zone between the borders, as a neutral zone, we held an event and a ceremony, remembering.

Q- In the first World March you went to difficult places, like Palestine or China.

R. There was an offshoot. What happens in these marches is that they escalate. We designed the first one, but then new things were added and one of them was the Middle East route. I didn’t take part in that, but there were people who started in Palestine and travelled all over that area, until we came together in Italy and activities were carried out in all those countries.

P. And now you’re preparing another march… There might not even be a world left for that march.

R. Yes, we are preparing the 3rd World March that will start and finish in Costa Rica after travelling around the planet, it will be in 2024. Now it makes more sense than ever because we are in a very complicated situation.

P. Besides, I know that you know Russia…

R. I was in Russia. I lived there for seven years and wrote a book. I wanted to write about socio-political issues. I went there at the time of Perestroika (Reconstruction) and also of Glasnost, which is Russian for “transparency”. There I had relations with the media here and tried to make socio-economic analyses of the situation. I used to comment on everyday life in Russia. Here there was a great lack of knowledge about the Russian people. You heard something about the Central Committee, the Kremlin, the Politburo, but little else. Nothing about Russian life. When I told anecdotes I had experienced first-hand, such as the fact that there are times when it is thirty degrees below zero or that the buses arrive exactly on time because you can’t wait in the street and they open the doors, a long-articulated bus and a large number of people for a single driver who drives and gets paid, the question that arises is how you can pay for the journey, although I was already warned… People remove it and pass it from hand to hand to the person in front of them, until it reaches the driver, and after ten minutes you get your ticket back with the change.

Q. What discipline! Just one anecdote shows the ability of this people to coordinate the simplest actions.

R. Of course, I commented on all this and the director of the media said to me: “Why don’t you write about it? These anecdotes ended up being the most read part of the magazine.

P. That’s important because now look at what a monstrous image is being projected of Russia and its people… They are portrayed as cold and heartless.

A. A totally wrong image. They are very caring and admirable in many ways. In their culture it is frowned upon to send a four-year-old child to school without knowing how to read and write perfectly well, and they learn at home. In Russia, I was a bookseller and the visas were every three months. I had to leave Russia every three months and come back. They took advantage of that because it was good for them to get paid in dollars, which was interesting at the time. I was changing my residence, I was in no less than twenty houses in the seven years and in none of them there were less than a thousand books. In my bookshop there were at least five or six thousand at least…

Q. How do you explain this conflict, in a very thick stroke? Is it such a dead end?

R. Former Spanish diplomats who have been in Ukraine and Russia have said so. When the Soviet Union was dissolved under Gorbachev, the Western leaders, especially the United States, made a commitment that NATO would not expand into the countries that formerly formed the Soviet Union, and that is the opposite of what they have done. Last but not least, there was Ukraine.

You have to know Russian history. Before Moscow existed, there was the Principality of Kiev, a Russian principality. Russian culture is fully embedded in the Ukrainian people. The main Russian nuclear ships are named after Ukrainian princes. In 2014 a US-backed coup d’état overthrows a pro-Russian president. There are bombings on its own territory, as if here in Spain and from Madrid, bombs were dropped on the Basque Country or Cuenca. The OSCE has documented fifteen thousand deaths caused by the Ukrainian government’s own military actions against its own population. Zorrilla, the Spanish ambassador, gave a talk in the Basque Country and said that he could talk about it, because he was already retired, but he has seen children with parents who had been mobilised in this war and at school were not allowed to speak Russian, when all their ancestors were Russian.

P. Has Putin’s threat of all-out nuclear war been exaggerated or does it pose a real risk?

R. It seems to me that it doesn’t depend on Russia. It depends on how far they want to push. It is naïve to think that the Russians are going to lose this war. In the First and Second World Wars, the Russians had the most dead and wounded. They alone almost equalled the sum of all the other countries.

P. So, is it naive for you to call for the withdrawal of the Russian army from the territory of Ukraine?

R. Yes, it is totally naïve because it is not a problem of Putin, it is a problem of the threat that they interpret, because what comes from Ukraine, and has developed in the way it has developed, for them are fascist groups that strengthened and belonged to the Third Reich. That is where some of the ideological nuclei of German fascism come from. That is the interpretation. The aggression comes from those who left more than fifteen million dead in Russia.

P. So, is there a non-violent way out?

R. There would have to be a real agreement. There would have to be a recognised international mediator. The United States has eliminated these modes of mediation. I remember there used to be those blue helmets as arbitrators. In a war, the first thing you lose is the truth, everyone tells their own story. When I recently told people in Costa Rica that in Spain they censored, for example, a Telegram channel for security reasons, to prevent them from hacking your mobile, they thought it was incredible. No, I told them, in Spain they don’t allow you to give out any information, it depends on where it comes from…

P. So, do you think it’s difficult to find a solution? Would Europe have to move without the influence and control of the United States?

R. Obviously, but not only that. We had the wrong idea of Europe’s freedom. At the second World March, talking with friends from Chile, about eighteen friends, almost all Latin Americans and two Italians, the discussion was: which democracy is more democracy? One of the things the Italians said was that democracy in Italy is different from the democracies of Latin America. I would say to them, “Do you know how many military bases there are in Italy? When they told me two or three, I will be quick to ask them to look them up on the phone and, response: although we don’t know exactly, at least thirty-two came up. I would ask her for the number of marines on Italian soil, response: this is reserved information, but the estimate could be between fifteen thousand and fifty thousand, because this information is secret. How many nuclear bombs are there? response: At least fifty. How many years have these bases been there? response: At least seventy. Do you think that a democracy that is already seventy years old and has foreign bases can be called a full democracy? In Latin America there are countries with far fewer years of democracy that do not have so many bases. The Italians have to request permission from the boss to spend one euro on armaments, and the Germans have to request permission from the boss to spend half a euro. The boss is the USA.

P. Gorbachev’s main proposal was a solid and permanent agreement between Europe and Russia. A great Europe that made the United States uncomfortable.

R. And it was articulated early on and there were problems with communism. Reports were issued. What bothers the Americans is that Russia is very big, it’s huge, it’s an area with eleven time zones. Madrid with the United States, with the West Coast, has seven.

P. In any case, Putin is not Gorbachev…

R. No, he was against it. Besides, the naive say he is a communist, Putin is an oligarch. I have seen how all the big businesses were distributed among the children of the high dignitaries.

Q. So what can be done? The outlook is very dark.

R. No, on the contrary. We are finding out what was already happening. There is nothing new, but the confrontation is also opening up and becoming more extreme at the social and international level. I think that the Yankees and the West, led above all by them, had neoliberalism with its maxim of free trade and free markets, and they have ideologically charged it. Now Russian oil has a different price, not because of market freedom, but because of its origin. Russian oil is worth less. They have kicked away their ideological basis. They were based on the idea that you have to be competitive and go for the highest bidder. That is backfiring on them in the United States itself, which is the cradle or one of the cradles of democracy, and now they have a country on the brink of civil war. Possibilities are opening up because people are realising and, when you look at television, what happened thirty years ago, when people believed it, is no longer happening. Now, when someone talks, people know that they are being deceived, even if it is the official truth. It’s not like that. People know when they are being told the truth or not.

P. It is clear to me that the target is Europe. It is being disarmed.

R. Of course they are.

P. The whole incomplete construction of “welfare, rights and freedoms” is being dismantled and impoverishing the population.

R. That is what they intend to do, and they also intend to do a test in Europe because the big problem is China. Do you think Russia preoccupies them? Let’s remember a little over a year ago, in August, when the NATO army left Afghanistan. It was disastrous. The biggest arms complex in the world, with super technology, ran out against an army of almost bows, arrows and stones. They couldn’t handle it.

P. We seem to be heading towards a monstrous globalisation.

R. That’s what they want. They want to remain the gendarmes of the planet, but not any more, not any more. And they are generating precisely what they didn’t want, they are accelerating it.

P. You’re not going to go there, but we see clearly that the pandemic is part of the agenda.

R. Ah, well, of course. I’ve been following the Hopkins University data, I don’t know if you know it. I’ve been looking at all the tests and the same guy who created the PCRs said it’s not good for that. And they haven’t isolated it or anything. They’ve put a bluff on a bluff, and we’re still there.

P. The population is in shock. You talk about another world march, but the people, especially here in Spain, are totally demobilised.

R. Well, we are going to do it anyway, but in a different way.

P. Tell us…

R. There are some people who say “it’s good that the system spills out…”, and I say “you have no fucking idea what it means when the system spills out”. When the system spills out, it means that there is no more electricity, no more bread, no more internet and that barbarism is everywhere. So it’s the armed groups and the small factions that… I don’t think that’s the best world in which to move forward. We have been studying the issue of exemplary actions for some time now and I was telling an acquaintance that there are cases of people who want to do something, but don’t know what to do. We invite these people to reflect, to think about their children, to think about their family, about their grandchildren if they have any. In a crisis situation, what action would you take that makes sense to them and has permanence? In other words, not just an explosion of one day that I go to a demonstration and then forget about it. Half an hour a week or an hour – does nobody have an hour a week? What would you be comfortable doing? And the most important thing is that it has meaning for you and hopefully you see that you can tune in with others. We think we are unique, but there are thousands like us. What happens is that we don’t show it and we think we are unique, but if we opened up we would see that there are lots of Rafas around the world, very similar, and lots of other people. So what do I do? Everyone can see. Well, I’m going to join a choir, perfect, I’m going to sing, and am I going to climb it or not? And what do I do? Every Saturday, for half an hour or an hour, I do the same thing and I repeat it and improve it, and I can invite other choirs. Suddenly I discover that in Vallecas or Lavapiés there are about 25 choirs, 25 choirs in Vallecas! So, at some point we can get together and there are already people who are putting the choirs together. So, it’s growing and there are some who say “come on, that’s in Vallecas, but we can do that in any neighbourhood”. That’s what happened against the war, when they got together in the Reina Sofía. Of course, there weren’t many of them, only three thousand five hundred singing. Well, that’s fine, what’s the problem? And then someone said: “Let’s do it on a European level”. At that level they wanted to gather a hundred thousand, but they only gathered thirty-five thousand. But that was cut off and what we are proposing is that there should be a process, that there should be empowerment of the people and that this should be scaled up. That it continues…

Let me give you another example. In World without Wars, in Costa Rica, there were some young women who wanted to form “Mountaineers without Borders for a World without Wars”. They go hiking in the mountains, they take the opportunity to spend half an hour or an hour there and they do workshops, they read things, they do exchanges. And they told us that, if there were people in other countries, they could get in touch with each other and help this to spread. But, in view of the whole issue of the march and also because it is very different if you do something out of the ordinary than if you do something very common, then it attracts a bit more attention. In her case, she said: “Let’s go up to the Cerro”, as they call the highest mountain in Costa Rica, very well. “What if we connect with people from Ecuador and they do the same thing and go up there too? I asked him: “You can be sure that if we do that in three or four countries, we will move the whole of Latin America because, as soon as there are three or four countries that climb the highest peak in each country, someone in another country will say that they will do the same”. This is how the mega-marathon has been set up, and we are about to define the Latin American date, which is another of the actions.

Rafa continues linking some images with others, some actions with others, and always with the idea of making concrete, of finding the proper sense of an action and of upward, of upward, of upward the scale of that action, which starts small and can reach an enormous dimension. There is neither space nor time to reproduce such a large number of images and, after a while, we interrupt?

P. But this newspaper comes out in Lavapiés, and all this can be quite far away.

R. But you can do the same in Lavapiés. For example, I was talking to a person in the Ópera area about the possibility of him going out and walking around the block twice with a sign saying “No to war”, and then I sit on this bench and talk. If you do that for three or four weeks, it’s going to be very easy for people to come up and talk and ask her why… And it’s easy for you to meet someone in Vallecas who says they’re going to do the same thing.

Q. What date is the march for?

R. These are preludes to prepare for the march. The march will be in 2024, on 2 October 2024. What we want to transmit is the idea of moving the valid individual action, the referential action, the exemplary action.

P. All this that you are proposing, are these actions to prepare for the march?

R. Yes, they are actions for people to empower themselves with the capacities they have and after the march it serves to interconnect and to globalise. With the human symbols of non-violence there are about a thousand schools.

Dozens of images, conversations and experiences are taking place at this moment and Rafa does not stop talking about them. He tells us about common friends and unknown friends. Of marches on foot or by bicycle that are already being rehearsed, of symbols in schools and squares, of a torch that leaves Hiroshima and goes around the world and ends up reaching Nagasaki, of recent and past conversations with very diverse people with greater or lesser influence and, above all, of launching each one’s own action and of scaling it up and connecting it with other converging actions. Finally, and in the face of our unsuccessful attempt to return again and again to the neighbourhood, she says…

R. There have been people who have travelled around the world without leaving their neighbourhood, travelling around the communities. They went to China, to Ecuador, or to Senegal, connecting with the emigrants in the neighbourhood… And so they followed the same route as the World March. This would be possible in Lavapiés…