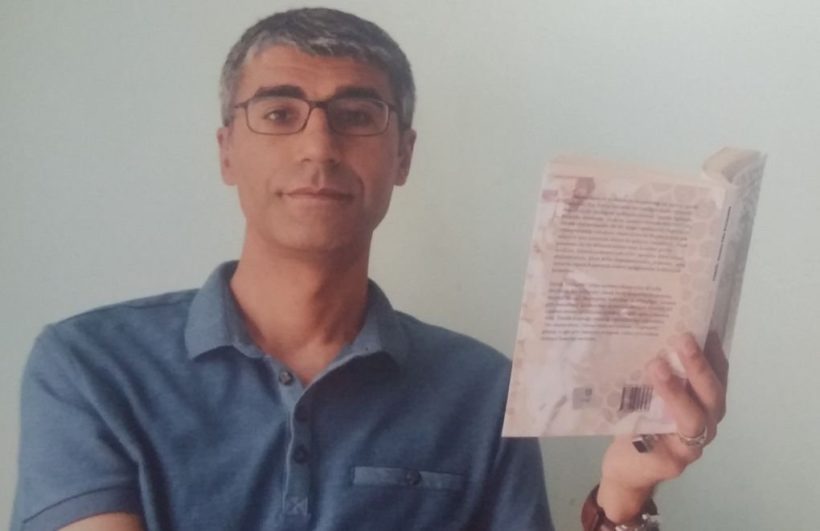

This is the second part of our conversation with Ilhan Sami Çomak, who has been in prison for the last 27 years. Ilhan has written eight books of poetry. In part I of the interview, describing his situation, Ilhan writes:

Prisons must have been built to place boundaries around the body, the eyes and the soul. But I’m still lucky; we have some budgerigars, and being able to touch them is a lifeline that quenches my thirst in this concrete desert. It’s somewhat contradictory that my company here consists of birds, who are known for their borderlessness. But on the other hand, the fact that they are reminiscent of freedom makes them the perfect companions and gives me a lot of pleasure.

By Jhon Sánchez

The European Court of Human Rights ruled in his favor. However, as Ilhan says, “For six years, my file has been at the Turkish constitutional court after an application from the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR)in 2014. I’m waiting for an answer to my appeals, but they persist in their silence.” And even though, Ilhan and his legal team had tried to prove his innocence, he writes,

Facts are not so important to the powerful. They are determined to browbeat people into accepting their words as truth. That is why there are courts in this country: to be the hand connecting the words of the powerful, reaching out with impunity to take you by the throat and suffocate you by throwing you into a cell, a hand that suppresses democratic and legitimate wishes, enforcing discipline and keeping everyone in line by delivering these kinds of punishments. As a Kurd, this has been my reality since birth.

To read part I of interview click here. #Freethepoet

JS: I read the poems I found available in English, mostly at the website, Free the Poet İlhan Çomak, sponsored by PEN Norway, but can you describe to us your literary work? Number of books, themes, style

ISC: Up until now, I’ve had quite a lot of articles, book reviews and interviews published in newspapers and magazines. Even so, I can say most definitely that the focus of my literary work is poetry. Right from the start, poetry has been an absolute passion of mine, I always knew what I wanted from it. Therefore, all my creativity has been channelled into poetry.

So far, eight books of my poetry have been published. And by the time you get this interview, another book of mine will have been published, “Leaving the Ant’s Nest Undisturbed”. It’s an autobiographical work that focuses on my early childhood and poetry.

To write poetry in prison, with all the difficulties it entails, you need to take yourself you’re your poetry seriously. As well as that, it’s vital to love poetry and have the determination to persist with it. I have to add that writing poetry in prison is in no way the same as just writing poetry. In the void left by the removal of different life opportunities and possibilities, in the deprivations of being imprisoned, it carries meanings more rooted in emotions, more on a par with life and more foreseen, meanings that make a person more full of affection and understanding of themselves and others, gradually going beyond a form of expression. It’s like finding yourself in the familiar world everyone knows but experiencing it entirely differently.

In my view, the reason might be this: I use my powers of imagination to write poetry. And instead of gravitating towards the life I lost or which was stolen from me, I gravitate towards an emotional world where goodness, kindness, friendship and love are always present, always in mind, out of reach of the malice strewn by humanity. I have searched for whatever is beautiful, whatever is favourable to humanity and nature. This search welled up from the poetry, brimming over into me of its own volition. The words I have written – the beautiful, warm realm of compassion – were created by me; but at the same time, they have led me to emulate them. Either that, or I wanted to be like the things that are missing from here, the things I wanted to find.

Just as with other aspects of my life, I always try not to compromise on authenticity when it comes to poetry. I try to present what is in me and avoid any emotional pretence. Being disconnected from life has deprived me of the experiences that can give such a rapid education. That has meant that I needed to hone my sensitivity, to approach life openly with all my emotions. That must be why I resort to imagination, skill and perseverance more than others.

Actually, I have never adopted one specific approach or style when writing poetry. It’s true that my poetry is generally lyrical, but it is built around imagery in equal measure. In actual fact, I have never worried that it must be this way or that, or tried to limit myself with specific definitions. The poems followed their own path and still do. My poetry changes, we both change together. I know these definitions don’t exactly fit with the poems I am writing today.

To be honest, I’m not very interested in definitions. I work at my poems because that is the wish of my soul and my mind. While I might consciously write the first word, in many ways I don’t know where it will go after that. I can only see the complete poem when it’s finished. While I’m writing, I try not to restrain myself. I try not to restrict the poem with definite, specific mental directives. Because when you try too hard to draw out the words, it affects the poem – you end up with something soulless. I can’t expect someone else to believe in a poem that I don’t believe in myself.

I adopt a fluid structure, shying away from controlling every moment of the poem with a preconceived idea. My approach is more powered by emotions, placing importance on the viewpoint of the reader and opening up space for it. But this approach is definitely not a shortcoming arising from carelessness; I trust in my ability, which has been honed after working incessantly for so many years, and I trust in the poetry itself. I work extremely hard. Inside this cordoned world surrounded by walls, I work hard to hear the voice of poetry in everything. That’s where my trust comes from.

Birds, sea, sky, water and rivers, trees and flowers, leaves, meadows, stones – these words occur frequently in my poetry. They form the backbone of the poetry’s themes and images. Therefore, my poetry is occupied with the things I have lost, with freedom itself and the natural world that comes with it. They never give up on it. The things that have been lost, the things that are missing, become my guests inside poetry, all the while accompanied by my constant desire to hold another living thing, to be without sorrow. Of course, only one aspect of it is like that. In the entirety of my poetry, you can also see an effort to look more widely, to speak about everything that concerns humanity.

This morning[1]

By Ilhan Sami Çomak

I look at you in the morning

and cut back the weeping willow.

Buds grumble and thirst for growth.

I look at you, scatter my own ashes.

I go out, add suns to the sunlight, walk on seeds.

Creation crashes down on me, the fingertips

of silence lightly restore balance.

I am on the hillside, shoulder to shoulder

with the rain in the uprising smell of soil.

On the sidelines are some words left unsaid.

I leap into the mystery of prayer and

laugh a little, grab hold of the breadth

of the breeze – how high are the clouds!

Roots look to earth and I to you.

I comb my unkempt hair.

I make my mark at the furthest point away,

feel the resonance of pain, the flowing of mirror’s

reflection. The night is naked, flames impatient

to shoot. I have a few breaths left. My body tires.

Ashes of sudden silence rise up

and creation crashes down on me.

İlhan Sami Çomak (born 1973) is a Kurdish poet from Karlıova in Bingöl Province in Turkey. He was arrested in 1994. In jail, Çomak has released eight books of poetry and become one of Turkey’s longest serving political prisoners. In 2018, Çomak won the Sennur Sezer poetry prize, for his 8th book of poems, Geldim Sana (I Came to You).

Caroline Stockford Turkish-English Legal and Literary Translator. She serves as Turkey Advisor for PEN Norway.

Jhon Sánchez A Colombian born fiction writer, Mr. Sánchez, arrived in NYC seeking political asylum where he is now a lawyer. ‘In 2021, New Lit Salon Press will publish his collection of short stories Enjoy A Pleasurable Death and Other Stories that Will Kill You.

[1] Translated by Caroline Stockford