There is one thing that is universal and that is art, because art can also be present in health (Italivi Elorza Velasco)

By Karla Mijangos Fuentes

This time at REHUNO we took a turn at the concept of health, and for this we took the hand of the Oaxacan artist of and for children Italivi Elorza Velasco. Originally from Miahuatlán Oaxaca, Mexico, a Zapotec town located in the southern Sierra Madre of Oaxaca.

At the beginning of the conversation with Italivi, she tells us that by appropriating her artistic qualities that have always accompanied her, such as singing, theatre, radio, storytelling, among others, she discovered over the years her interest in working with Oaxacan children.

Her interest stems from the personal, because with the arrival of motherhood she discovered a remarkable change in her life, and by this we are not only referring to a change of habits and practices, but also to a change of paradigm. Italivi points out that her daughter “educated her”, because since she knew she was pregnant, she was constantly questioning how she was going to prepare the nest for this little person and how she had to prepare herself to take care of the physical and emotional aspects.

“I started to study different ways of early stimulation. And in this research, I realised that also singing and reading stories to her was another way of stimulating her, something different from what we understand as early stimulation. And from this stage of motherhood, I became interested in working with children,” she says.

Italivi rescues the subjective value of environments, aware that there is no single way of naming, signifying and creating environments that are conducive to children growing up in a space that enriches and nurtures them constantly.

Environments are ideologised and thought from institutions, both in private and public spaces, and never from other imagined or constructed places in the territory. This is where she focused her interest, especially because she was concerned about these other children who do not occupy these categorised spaces and who are also worthy of receiving these rights.

She was interested in placing in the environment the elements that are necessary and possible for the development of children. From this perspective, she points out and reflects: “And that, with this, we can really fulfil this promise to respect them and that they can exercise their rights, and one of these rights is recreation”.

“Art plays a fundamental role, which may seem a little banal, but the truth is that at this age we see how art, play, caresses, caresses, caresses, songs, all these processes that may seem very simple, are what gradually enrich their development of speech, psychomotor skills, etc.”.

In her self-description, the Miahuateca artist refers that she does not have the papers that accredit all her knowledge on the subject, however, from her own experience of motherhood and life, as well as from other spaces of training and participation in different educational projects, she has built a wide range of knowledge and experiences that legitimise her in her community and in the whole state of Oaxaca.

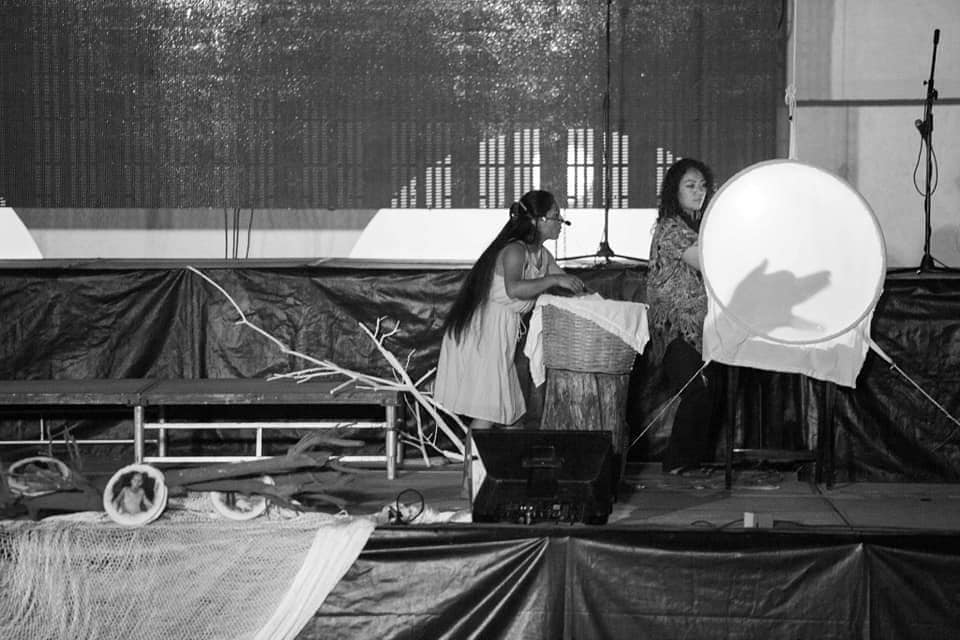

(Italivi during one of her workshops)

And from this knowledge, Italivi has built these spaces and activities that empower the development of Oaxacan children. She has created various projects with children that are not always located in schools, but in these other territories where they live and can explore and understand; and it is precisely here that REHUNO’s interest in creating this conversation was focused.

As Italivi points out, the space is not determined by the school, but it is the children themselves who configure the space. So, the whole exercise starts and revolves around what the children decide to do and learn in their day, so the space must also be adapted to those interests. “I have even taught in the street; we have taken over parks and other spaces like pavements. That’s why I say that spaces are more about how we appropriate them and how we conceive them when we work.

At REHUNO we reflect with Italivi on the meaning that we as a society have assigned to recreation. Normally it is located in public spaces (parks, schools, centres of attraction), however, the COVID-19 pandemic has also overturned these forms of recreation, because now the home has become everything. And from this context, many of us now wonder how to fulfil our children’s right to recreation.

Our guest questions us by putting on reflection a premise, which she acquired through the teachings of Master Emilio Lome, (Miguel de Cabada Fine Arts Award for Children’s Stories 2020) and which points out: “the caregiver must be taken care of”. In this line, Italivi describes that in order for a person to be able to provide the care and support to their children, they first need to give themselves a break and look inwards to know how they are doing. In this direction, Italivi gives us the following teaching from Emilio:

“Even if it is only for five minutes, let’s put a hand on our heart and from there take a deep breath, close our eyes, imagine that we are a balloon and breathe. That way we give ourselves that little space to refresh ourselves, to clear our heads, to rest a bit from the hustle and bustle; and now we can think about what we are going to do with our children, which is why what I always propose is very much to the body, because our body has memory, our body speaks.

She is also certain that not all people have the experience and knowledge about these other forms of recreation because there is a low level of dissemination of these strategies. But she also affirms that in the face of these other ways of thinking about the consequences of stress in children during this time of pandemic, and that many times this is related to the environment that children live in at home, the important thing is that there is the intention of the family to attend to these dimensions, because from there the environment changes, as Italivi points out “from there the look is towards our children, that is basic and super important”.

With the main tool in hand, which is the intention of the caregiver, Italivi invites us to accompany our children looking for a time of the day to lie down with them and ask them to close their eyes, take their hand (if possible) and start talking to them, starting with the breathing exercise, then guiding them through the imaginary of the body and then taking them to a place they like, making use of this great capacity of imagination that they have.

This children’s relaxation strategy, which we are talking about today, allows children to learn to give themselves space to breathe, to place themselves in the here and now, to have a routine where they are aware that at some point in the day they will relax and let go, because what these exercises are all about is helping the child to connect with their emotions, with their discomfort. As Italivi says, “I think this is the key to understanding many of the emotional problems, be it bullying, violence, hyperactivity. I am not proposing this as a solution either, because there are also diagnostic issues, but I think it is a great ally”.

Thus, we see that, with these other ways of looking at recreation and art in childhood, we also break down adult-centric utopias, which revolve around thinking that these exercises were designed exclusively for adults. Moreover, as Italivi comments, it also breaks paradigms about the expectations that many of us have about relaxation exercises, for example, that to achieve a full state of relaxation requires a certain position and space. However, the children have deconstructed us about all these thoughts and doings.

“With the children I have learned in all these years of work that we have to let go of all those ideas we already have, that ideal thing we think, that expectation we have to let go because in this exercise there will be children who from the beginning when you tell them ‘let’s do the relaxation exercise’, they will say ‘come on, let’s relax! but there will be someone who will say “no, I don’t want to relax”, or there will be someone who doesn’t follow the instructions, for example, to close their eyes, to lie down, and this is an important part of respect for them, for their body. Also, there are some who relax in the first session, some others until the fifth, but it’s all a little at a time, so I also invite them to develop it at home”.

One of the forms of knowledge that we appropriate today from Italivi’s thinking is the reflection on art as a health strategy, but also as a right, because, as she pointed out, art is a right for any human being, and even more so for children.

However, art has been tainted by a demonised idea, because it would seem that the exercise of art can only be accessible to a certain social class, to people with very particular characteristics, and mainly, that it can only be exercised from academic and sophisticated spaces.

(Italivi Elorza Velasco)

In this sense, Italivi agrees with REHUNO, but also reaffirms and revives his idea of the felt need to take paintings out of museums, music out of the theatre and forums, and art out of the academy. All this, with the aim of bringing all these tools to the spaces where our children are located, because as Ita says “the truth is that art is everywhere, wherever we go there is art, for example, painting is one of our great allies when we want to work on fine and gross psychomotor skills and when we want to work with concepts and numbers”.

She also proposes music as an artistic tool and tells us that other spaces of creation, innovation and movement are developing from there, for example, the existence of bands that are working on the papiro-fléxica of Mexican painters to describe the life of the painter through songs, or there are even groups of rappers who give stories in their musical art.

As well as music, dance, singing and theatre, which are more positioned from the concept of art and recreation, there are other forms of art and health, such as paintings, poetry, songs, games, relaxation, among others. The most important thing, as we could see, is the intention and the discovery of the interests on which our children’s construction initiative is based.

“We must let go when we are with our children, let go of that adult position, go back to being children, let go of the body, the spirit, because many times there are very ceremonious fathers and mothers who want the children to do everything very formally and many times what they need to do is to muss their hair, run, hang on to a rope that challenges them to use their weight. We have to get out of our little box to look for those other tools that we surely have there, but we haven’t seen them.

For example: “Don’t be afraid to sing to your baby, your voice is the most beautiful, let’s not wait until we have everything ideal to do things, let’s have that intention”.

“Definitely, this pandemic has taken away these face-to-face spaces, but I always say that my spaces are imaginary, wherever I can: on the radio, in sharing a reading at night through talks, in sharing what we do so much in Oaxaca, because I think that in the end these support networks are what sustain us at this time.

For more information about the work that Italivi does, we leave you with these recommendations about some pages and spaces where you can find it.

- Semillitas Radio Oaxaca (radio and play laboratory). Available at: https://www.facebook.com/italiviev/

- Capsules on early stimulation for Alas Raíces Oaxaca. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FvEyu2WHWGk

- ABC music academy. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/Abc-Music-Academia-De-Musica-145430202247865

- Readings to accompany ourselves and others (Sundays 10 or 11 p.m.). Available at: https://www.facebook.com/italivi.elorzavelasco