By Jhon Sánchez

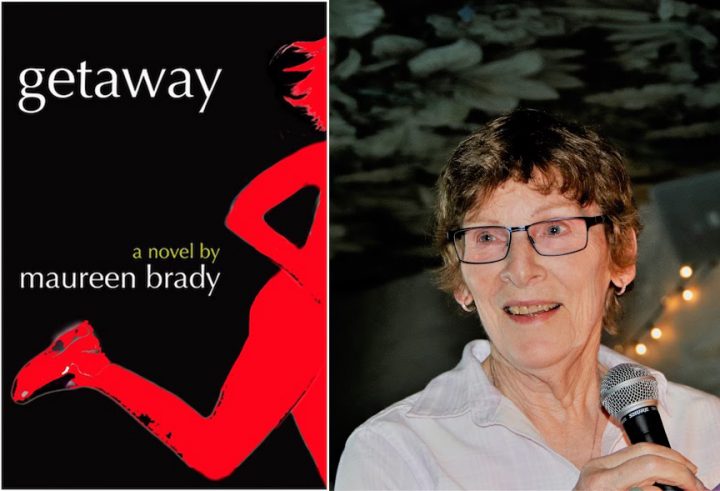

Recently, I read ‘Getaway’, a novel by Maureen Brady. In the story, Cookie escaped from her violent husband, and she tries to live under a new identity in Canada. Given the importance of the #Metoo Movement today, I decided to have a conversation with Maureen about her novel, domestic violence, and women’s rights. Maureen thank you for accepting my invitation.

JS: Why did you write this novel, Getaway? Were you impacted by the ME TOO Movement?

MB: I started writing Getaway several years before the Me Too movement broke out, but I’ve been a Me Too advocate using difference names since the Second Wave of Feminism, in which I was heavily involved. Some of the discussions I have had with readers of Getaway, when attending book clubs who have read the book, have been provoked by the novel to discuss their own personal experiences with domestic abuse and workplace harassment. I have been glad to see the novel work this way and was certainly glad to be releasing Getaway into the newly energized atmosphere of the Me Too Movement.

JS: You chose to use heterosexual characters in the context of domestic violence. Do you think domestic violence differs within the LGBT community?

MB: I hope and suspect it is less prevalent, though I know it exists in all communities. Most of the people I know from whom I’ve gathered life experience, at least those who were lesbian, had been abused in a prior marriage or heterosexual relationship. But abusers come in all shapes and sizes, and so do those who are vulnerable to choosing them as partners, so no group is exempt.

JS: Much of the story is set in Canada; how did you prepare to write about Canada and Canadians?

MB: I made two research trips to Cape Breton and had visited there once many years before, and that first trip provoked me to choose it as Cookie’s getaway place, because I was struck by how it was at once stark and stunning, and I felt she needed somewhere like that to begin healing, as well as, of course, it had to be as far away as possible. I enjoyed visiting a great, small library in the area Cookie escapes to, taking walks she might have taken, and interviewing a lobster fisherman who loved to tell his sea stories.

JS: Cookie’s experience is similar to many women around the world who try to flee their husband’s violence and ask for asylum in the USA. Last year the Trump Administration tried to curtail the basis for asylum for those women. Could you comment on that?

MB: To me, it seems criminal. These women are in dreadful and life-threatening situations, both in the USA and abroad. It shows us how far we are from equal rights that they are often not listened to or believed. We are inhumane not to open our doors to them. If I put myself in their place, being abused not only by a spouse but quite possibly by a tyrant in their home village, maybe having the lives of their children and their own lives threatened, I can understand what sustains them to walk for many miles, hoping to reach the border and find some safety, despite the knowledge that our system is broken and they cannot have high hopes of being approved for asylum.

JS: Your novel is also about alcohol abuse. You dig deeply into the character of Cookie’s husband, who is an alcoholic. What was the process of writing this part of the novel?

MB: I was interested in exploring what sort of effect alcohol has on someone who might also have some kind and good instincts when not under the influence. And I wanted the abuser (Warren) to be someone who might be considered to be a nice guy in his community. Black outs are a very real effect of excessive use of alcohol and many alcoholics wake up not knowing what they did the night before. I also wanted to bring up the possibility of Warren finding sobriety and have a shot at giving up his old behaviors.

JS: Reading your novel made me think that perpetrators of domestic violence suffer from a kind of illness. Legally speaking, should we treat them similarly to drug addicts?

MB: That’s a broad question, because mostly we treat drug addicts as criminals because they resort to criminal behavior. And certainly I think we should treat perpetrators of domestic violence as criminals. But I also think we need to use the illness model to develop ways to intervene, to provide effective treatment that can offer a person who is perhaps passing on the violence that was perpetrated on him or her at an early age to someone who is in a less powerful position. Otherwise, the cycle will just keep repeating.

JS: You take time to describe the early signs of violence in your character’s relationship. Do you think your novel would help potential victims of domestic violence to sever ties with their husbands or boyfriends who show signs of abusive behavior?

MB: Isn’t it always useful to see someone you recognize as similar to you depicted in literature in a way that empowers them? While Cookie exploded and certainly went beyond an ideal reaction, she did finally act in her own defense, and she began to discover herself once she was somewhat safe in Cape Breton. Also, it may be helpful to see the progression I depict, starting with controlling behavior, then moving toward more violent acts of physical and sexual abuse. On the other hand, abused women are notorious for returning many times to the abuser before they finally made a thorough break, for a host of reasons: Financial dependence, social dependence, and the hope they may be able to fix the problem, among them.

JS: I love your character Edith. She was almost like a detective. How did you build that character?

MB: I love Edith, too. She was a composite of a lot of women I have known. Someone who observes and holds the community together. Someone who appears conventional but was able to tolerate an unconventional marriage and was satisfied with whatever came her way in life and had a lot of empathy for others she perceived as struggling. And I wanted to make the point with her, that at some time in one’s life when one is down and out, there is often a crossroads meeting with someone who extends a hand, consciously or unconsciously, and that makes all the difference in one’s staying power, until one can get her feet on the ground again. So she does this for Cookie, and Cookie, in turn, does it for Chrissie.

JS: There is some way in which each of the characters in the book gets a second chance? Was that deliberate on your part as the author?

MB: Actually, it was not. When the galleys were sent out for blurbs, Aaron Hamburger wrote one that called it, “a tension-filled yet ultimately humane story about hard-won second chances.” And I thought, of course and was so pleased to realize that had happened but not by any plan or contrivance on my part. Of course, I wanted Cookie to survive, and at first, I did not intend for Warren to survive. But he had a different idea about that. And so I gave him the option of a second chance.

JS: Have you found any successful strategies for promoting the book?

MB: Yes, initially, I did a number of readings in the New York City and Upstate New York areas. But my most engaging events have been attending book clubs, some in person, some in cyberspace. Each has been a unique experience, but all have offered me a chance to learn interesting things about how the book has been received, and to partake in a stimulating discussion. I am available to do more of these on request and look forward to hearing from book clubs who would like a live author visit. Thank you again.

About the Authors

Maureen Brady is the author of eight books, including the novels, Getaway, Folly and Ginger’s Fire, and the short story collection, The Question She Put to Herself. Getaway, the story of a woman who stabs her abusive husband and flees to the far reaches of Nova Scotia, was released by Bacon Press Books in 2018. Her stories and essays have appeared in Sinister Wisdom; Bellevue Literary Review; Just Like A Girl; Southern Exposure; Cabbage and Bones: An Anthology of Irish American Women’s Fiction; and Banff Writers, among others. Her short story, “Basketball Fever,” won the 2015 Saints and Sinners short fiction contest and her short story, “Fixer Uppers,” was a finalist for the 2019 Saints and Sinners fiction contest.

She teaches creative writing at NYU, New York Writers Workshop and the Peripatetic Writing Workshop, and has received grants from Ludwig Vogelstein, Tyrone Guthrie Centre in Ireland, Money for Women, NYSCA Writer-in-residence, and NYFA. She co-founded the press, Spinsters Ink, in 1979, was a co-founder of New York Writers Workshop in 2001, and has long served as Board President of the Money for Women Fund.

Jhon Sánchez: A native of Colombia, Mr. Sánchez arrived in the United States seeking political asylum. Currently, a New York attorney, he’s a JD/MFA graduate. His most recent short stories are Pleasurable Death available on The Meadow, The I-V Therapy Coffee Shop of the 21st Century available on Bewildering Stories and “‘My Love, Ana,’—Tommy” available on https://www.fictionontheweb.co.uk/ . On July 1, The Write Launch released his novelette The DeDramafi, which will be also reprinted by Storylandia in 2021. He was awarded the Horned Dorset Colony for 2018 and the Byrdcliffe Artist Residence Program for 2019.