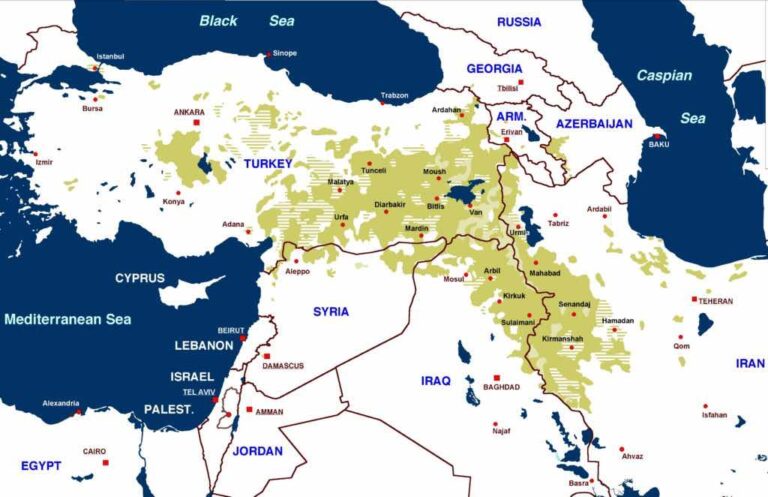

Parallel to the ongoing Israeli-Palestine war (and the Iranian-Israeli conflict), the last weeks saw several incidents both in the Levant and in Southwest Asia – and most of them pertain, directly or indirectly to Kurdish groups. Two weeks ago, Turkey struck power and water infrastructures in Syria’s Kurdish-held northeast and northern Iraq. Before that, Turkish soldiers had been killed during clashes with Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) militants in northern Iraq. According to the Turkish authorities in Ankara, ammunition warehouses and tunnels used by combatants were destroyed. In parallel, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard attacked what it claimed to be the spy headquarters of Israel also in Iraq’s Kurdistan. From the Levant to the Iranian-Pakistani border (home to Balushi rebels, who support the Kurdish struggle), the Kurds seem to be everywhere.

By Uriel Araujo

Different Kurdish separatist and militant groups are a concern today, to a greater or lesser extent, to the states of Syria, Iraq, Turkey, and Iran. The US Department of State has been consistently trying to turn its cause into an instrument of American geopolitical interests, with varying degrees of success. Such groups do not limit themselves to being proxies or to being used for leverage by great and regional powers; they also bring further unpredictability to a chessboard that is already complex enough in itself.

As I wrote, Iranian-Pakistani tensions have been on the rise over both nations having struck each other’s territory, while targeting militant groups that operate on their shared border. On Iran’s end, this was part of a series of retaliatory measures: on January 4 a terrorist attack claimed by the so-called “Islamic State” (Daesh) terrorist group, also known as ISIS, victimized at least 84 people in the Iranian city of Kerman; the Iranian authorities in Tehran retaliated by targeting what it claimed to be Islamic State terrorist targets in Syria and Kurdish-controlled northern Iraq.

The Baluch movement Jaish ul-Adl, responsible for the January 15 attack on a police station in Rask (southeast Iran), is known to cooperate with Kurdish separatist groups in Iran; it also denounces the Iranian presence in the Syrian conflict.

According to Dilek Doski, a Diplomatic Intern for the Kurdistan Regional Government’s Representation in the United States, writing for the Wilson Center’s website, the Kurdistan region is key to Washington’s strategy: “with the support of their American allies, the Kurds can enjoy their autonomy, security, and prosperity with long-term solutions, while upholding the US interests in the region”, she argues.

Iraq’s Kurdistan Region (KRI) is an autonomous administrative entity within the country, bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, and Syria to the west. The KRI has a local President, who heads the Peshmerga Armed Forces, responsible for local security. These forces had a key role in helping the US capture deposed Iraqi president Saddam Hussein in 2004. Kurdish autonomy was only recognized by Baghdah in 2005, after the US invasion of Iraq. Despite the KRI’s institutionalized character (from an Iraqi perspective), there are tensions: the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) also lays claim to the disputed territories of northern Iraq. Since 2017, after a non-binding independence referendum, the KRI has been calling for Kurdish state building, something Bahgdah rejects. The Peshmerga forces have been fighting alongside the Iraqi military, in their common struggle against the Daesh (ISIS) terrorist group, but there have also been clashes between them and the (Iran-backed) Popular Mobilization forces of Iraq.

In neighboring Iran, Syria, and Turkey, however, the Kurdish forces are considered rebels.

In Syria, the People’s Defense Units (YPG), a mainly Kurdish combatant organization, recognized as a terrorist group by Turkey, has been fighting the Daesh, but it is also a component of the so-called Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). This is a coalition that also includes factions of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), which itself is in turn yet another big tent coalition of forces that oppose the Syrian government of Bashar al-Assad. Many FSA officers notoriously have come to join the Daesh, a fact that further complicates the equation. The SDF has often been described as “mercenaries” working for Americans.

In Turkey, Kurdish separatist groups such as the PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party), as well as the TAK and HBDH, engage in various methods of insurgency, including terror against civilians and suicide bombing.

One should keep in mind that Turkey’s (a NATO member) “reluctance” to okay Sweden’s bid to join the Atlantic Alliance was vocally justified on the grounds of Turkish concerns about the Nordic country’s policies on Kurdish exile groups, but had everything to do with Washington’s policies regarding Kurdish separatism, as I’ve written before. The US has long supported rebel Kurdish groups in Syria, such as the aforementioned People’s Defense Units (YPG), and the Democratic Union Party (PYD).

From Ankara’s perspective, a Kurdish “statelet” adjacent to its border with Syria would be an existential threat, according to Halil Karaveli, a senior fellow with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center. Turkey’s message supposedly was that the US should be able to “sacrifice” its (Kurdish) proxy efforts in the Levant in exchange for having Sweden into NATO – something that Washington has been pushing (together with Finnish accession) since day one, as part of its NATO’s expansion strategy to encircle Russia – a strategy that remains one of the main causes of today’s conflict in Ukraine.

Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan in any case has “finally” signed off on Sweden’s NATO membership ratification, hoping to buy fighter jets from the United States. It remains to be seen whether the Americans, in a quid pro quo move, will change their Middle East policy or not. It is quite likely they will not. Erdogan’s Turkey has always played an ambiguous role within the NATO structure, clearly making good use of its veto power to obtain leverage, as we’ve seen with Sweden. One could argue Erdogan itself has long been a thorn in the side of Washington.

The US-backed “Kurdish question” therefore seems to be spilling over across the Middle East. Right now, after the Iranian strikes against their capital, Kurds in Iraq are demanding the US protects them. Mahmoud Osman, an influential Iraqi Kurdish politician, has stated that Kurds “must be vigilant and maintain a balance between the major powers and must not rely solely on the United States because the United States will not protect them.” One should keep in mind the fact that Washington betrayed them thus far by failing to support their independence after the 2017 referendum, as well as in many other instances.

Moreover, in some contexts, different Kurdish groups could emerge as a problem for the US: in 2019, for example, after feeling abandoned by their Western allies, Kurdish forces reached an agreement with the Syrian government, thus paving the way for Assad forces to regain the country’s northeast.

Uriel Araujo, Ph.D. candidate at Universidade de Brasília (UnB), journalist and researcher with a focus on international and ethnic conflicts