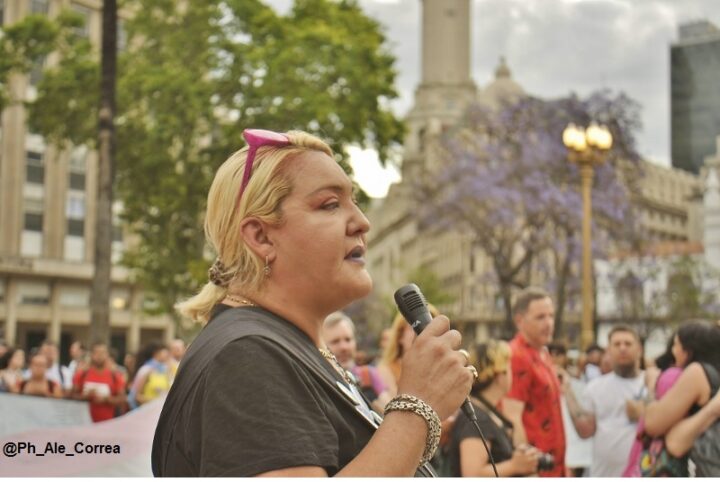

María Belén Correa, trans activist for the rights of sexual minorities. She is the creator of the Asociación de Travestis de Argentina and of the Archivo de la Memoria Trans, which documents the history of the struggles of this community (Image by Archivo de la Memoria Trans).

The feminist movement has made significant gains in Argentina in recent years, but all of them are now threatened by the government of the far-right Javier Milei, who denounced gender politics during his election campaign and, since taking office on 10 December, has shown that he is determined to put his ideas into action.

In a monumental bill, which in 634 articles will reform a large part of the economic and social life of Argentines, Milei seeks to end the gender parity that today must be complied with in all lists of candidates for the legislative National Congress and to eliminate training on gender issues, including violence, which today is mandatory in public offices.

These are just two of the changes promoted by the government, which made a declaration of principle from the outset when it liquidated the Ministry of Women, Gender and Diversity, created by the previous administration with the mission of combating discrimination and violence and contributing to a society without hierarchies between different sexual orientations.

“We thought we had convinced society that the feminist agenda is egalitarian and beneficial to the majority, but today we see how the idea has taken hold that these are the concerns of a minority”: Natalia Gherardi.

These are meaningless words for Milei, who on 17 January, on his so far only trip abroad as president, chose a stage of great international resonance, designed to discuss the global economic agenda, to provoke with his extremist discourse against feminism.

“The only thing that has become the agenda of radical feminism is more state intervention to hinder economic growth and give work to bureaucrats who have contributed nothing to society, whether in the form of the Ministry of Women’s Affairs or international organisations,” he said at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

Feminist movements marched on 24 January in different cities across the country during the first general strike against the Milei government, called by the main trade union confederation. The slogan was that they were not going to allow the reduction of the rights won for women.

Setback

“Feminist movements had an explosion in Argentina in 2015 and the phenomenon was such that we became a reference first for the region and then, for the world. Today that same monster has devoured us: the expansion was so powerful that it began to generate resistance,” lawyer Natalia Gherardi, with long formation and experience in working for women’s rights from civil society, tells IPS.

“We thought we had convinced society that the feminist agenda is egalitarian and beneficial to the majority, but today we see how the idea has taken hold that these are the concerns of a minority,” adds Gherardi, who heads the Latin American Team for Justice and Gender (ELA), an organisation that has been working for 20 years in favour of women’s rights in Buenos Aires.

Indeed, the discourse against gender policies seems to have paid off for Milei, a 53-year-old economist who gained popularity by insulting politicians on TV – whose image has deteriorated due to a persistent economic crisis that has lasted 12 years -, founded his own party in 2021 and had a meteoric rise to the presidency in 2023.

“In crisis situations, the thread is cut at the thinnest point and that is why it is useful for them to attack feminism and sexual diversity”: María Belén Correa.

Since he took office, he has been imposing an ultra-liberal programme that seeks to end all economic regulations that protect the most vulnerable. The result, for now, is an acceleration of inflation – which in December was 25% in a single month, according to official data – and an even greater deterioration in the acquisitive power of wage earners.

“We are the shield that Milei is using for it to make things stronger and more important, which is to disarm the state and apply an ultra-liberal recipe that has already been used before in Argentina,” María Belén Correa, an activist for the rights of sexual minorities who in 1993 was one of the founders of the Asociación de Travestis de Argentina (Association of Transvestites of Argentina), told IPS.

Correa adds: “In crises, the thread is cut at the thinnest point, and that’s why it serves them well to attack feminism and sexual diversity. The right-wing has always campaigned against minorities, making us the enemies of the rest of society.

She is the creator of the Trans Memory Archive, which with more than 15,000 documents preserves the stories of the community and of those who have been killed or died because of obstacles to access to health care.

Not one less

The great phenomenon of feminism in Argentina began in 2015, when the crime of Chiara Páez – a 14-year-old pregnant teenager who was murdered by her 16-year-old boyfriend – launched thousands of women to the streets to demand an end to male violence, in a movement that became known as “Ni una menos” (Not one less) and grew year by year, spreading to many Latin American countries.

From the bottom up, it gained the support of artists, politicians, academics and different social sectors.

Among other things, the movement succeeded in getting the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation to create a National Register of Femicides or gender-related murders of women.

According to the latest official register, in 2022 there were 252 femicides or feminicides in the country, which is 13% less than in 2019 when a peak of 286 cases was reached.

Another achievement was the so-called Micaela law on mandatory gender training for members of the three branches of government. It was named in honour of the rape and murder of teenager Micaela García – who was a member of the “Ni una menos” movement – outside a discotheque. Now Milei is trying to repeal it.

The high point of feminism came in 2018, when the social demand generated that for the first time Congress voted on the decriminalisation of abortion. It was a narrow defeat, but the fire was lit and abortion was legalised in 2020.