Silencing, denying and distorting events, a practice of great disloyalty.

Fake news, what we know today as Fake News, has played its part, in the 1970s and later, in a constant attempt to falsify history and memory. In certain newspapers and television channels, fictitious information was intentionally delivered under the guise of news facts, with the aim of pressuring, confusing, deceiving, manipulating and hiding what was happening in our country and altering the population’s perception of reality. This practice, which today is common in all social networks, has a content whose objective is disinformation and generally responds to interest groups that seek to install these lies to use them to their advantage. Thus, serious human rights violations were turned into news of a criminal nature for a population that was living through the breakdown of the democratic system, the dissolution of the National Congress, the proscription of political parties, the restriction of civil and political rights (freedom of expression, information, assembly and movement) and the constant violation of human rights.

For Alejandro Morales, head of the Digital Media Unit of the Directorate of Information Services and Libraries (SISIB) of the University of Chile, it is neither relevant nor correct “to speak of Fake News, because if something is false, it is not news, and if it is news, it is because it is not false. The correct term is disinformation, which is broader and refers to all false, inaccurate or misleading content intentionally designed, presented and promoted to cause public harm or particular benefits. Using technology and mass data, it seeks to deliberately alter the perceptions of large groups of people or societies and influence their behaviour.

Moreover, for Professor Ana María Castillo, journalist, PhD in Communication and co-director of the Artificial Intelligence and Society Nucleus of the FCEI, this type of content “prevents citizens from making informed decisions if they are exposed to deception and fake news” ….. “It is no longer just a matter of having different visions or opinions, but there are people who put forward distorted arguments, therefore, equitable dialogue becomes difficult and ends up being confusing”, which could explain, to some extent, why to this day, almost 50 years later, there is no common position on what happened during the civil-military dictatorship and its social and political consequences for our country.

The media’s handling of the processes for a new constitution.

No one is surprised that in the first process, from start to finish, the “press media” and TV in general had a magnifying glass on the convention members, and that today, in the second process, no one has any idea who applied, what they are doing, in a scandalously biased media silence regarding the constitutional councillors. The lack of news plurality in Chile is impressive, and that the verbiage describes it as freedom of the press is insufferable. Denialism has no thematic boundaries. It denies the inhumanity of a cruel dictatorship, the outrageous inequality, the crimes of an evil and discriminatory elite, a failed and obsequious justice system, the violence of a patriarchal culture and the pederasty of a decadent curia. There seems to be a profound belief that if crimes are not talked about or denied they do not exist. But this is nonsense, all their outrages exist, and they do not vanish because of the imposed silence.

The active nonviolence underway to overcome the civil-military dictatorship are facts that have been vainly silenced.

Fifty years ago, we were not part, as a political actor, of those who unleashed the tragedy of the breakdown and the agreement to perpetrate the civil-military coup d’état, which initially victimized Salvador Allende and then thousands of compatriots in the 17 years that followed. However, a decade later, we bravely embarked on the party-political path, in the midst of the most violent dictatorship in our history, from a new ideological source, with no links to those protagonists of the early 70s of the last century, always trying to make a contribution to overcome the monstrous dictatorial violence towards a stage of democracy, albeit formal, as it was obviously a response to the needs of the people at that time.

Opening up in practice the possibility for people to support a political solution, where more than 80,000 people from every corner of the country overcame the terror of the threats of being violated by a murderous civil-military dictatorship and gave their signatures, with their names and all their personal details, to young people from this new political current who came knocking at their door, is something that is difficult to appreciate today, but without doubt this action of being the first opposition party to the dictatorship to demonstrate that it was possible to become legal, was a decisive step in the events that followed.

Already on the way to the Yes and No plebiscite, the strategy we put in place to counteract the terror felt by the population, through very clear actions but wrapped in a ludic tone, which called to rescue subjectivity and bring to the present the possibility of a collective joy, which would leap over the monstrosity of the civilian and military rulers, with the cost of those arrested and imprisoned, was also a great contribution to the process of re democratisation of the country.

And on the day of the plebiscite, our effort to call for and manage a list of proxies to monitor every vote at every polling station in the country was another invaluable contribution.

The challenges of the situation half a century after the coup

Today we are still standing. We are determined to generate conversation, deliberation, reflection and the search for collective agreements in every space, whether our own or shared with others, assuming the richness of human diversity as something positive. This exercise of real democracy is not easy, but we are convinced that it is the right way to overcome the violent society we suffer today.

In the same way, we are defining our direction to face the present and the future of our political activity, as well as the best position to face the elitist constitutional process that will be voted next December.

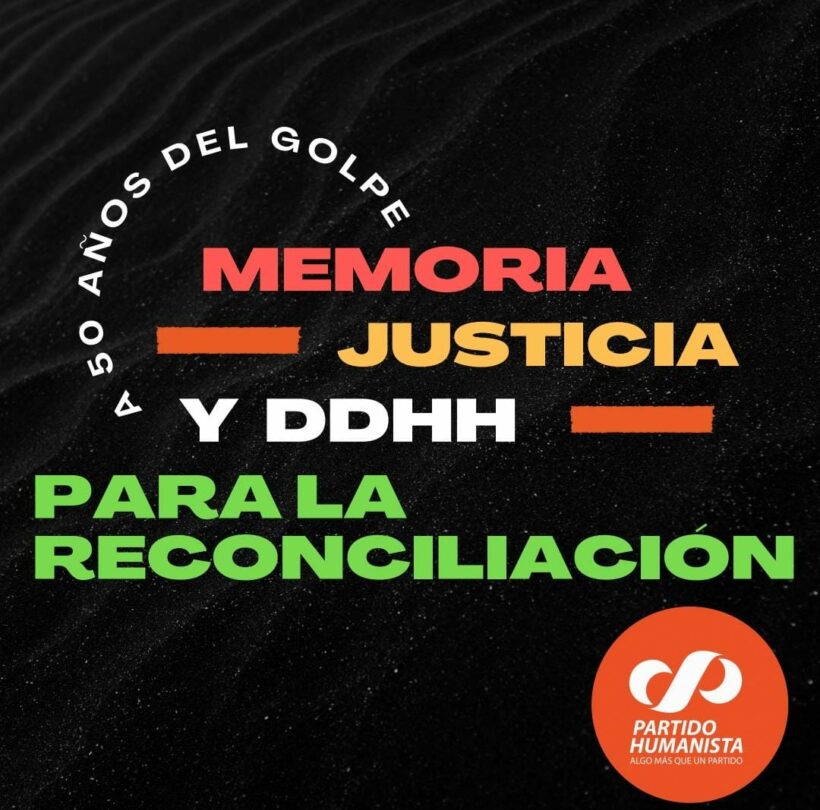

And in this commemoration of 50 years, we have collectively agreed to propose, to whoever will listen, to set in motion Reconciliation, personal and collective, which starts by doing what is necessary not to falsify the Memory, to give Justice to the victims and to commit ourselves totally to the defence of Human Rights; for us, but especially for the new current and future generations of our country.

Thus, this call coincides coherently with what Laura Rodríguez already expressed in April 1990, in support of the creation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the National Congress: …. “It is also a hindrance to consider reconciliation in a simplistic way, as an ignorant and blind forgiveness of the past reality”. (…) “True reconciliation takes place when we bring the events of the past to the present with as much truth as possible and manage to transform the traumatic charge they have, with understanding and the will to build a future that does not repeat these errors. It is wrong to believe that by discovering the truth, human beings inevitably fall into an attitude of vengeance. This is wrong and constitutes an irresponsible lack of faith in people. Let us not put-up false obstacles, let us not postpone our truth any longer”.

Collaborator: Sandra Arriola Oporto; M. Angélica Alvear Montecinos; Guillermo Garcés Parada and César Anguita Sanhueza. Public Opinion Commission