Mahatma Gandhi’s thought and political action represent the highest expression of the Indian cultural movement that aimed at the full reaffirmation of the essential values of the Hindu tradition against the slavish imitation of Western ideas, which had been developing along with the triumphant image of British colonialism, industrial society, opulence and nascent consumerism.

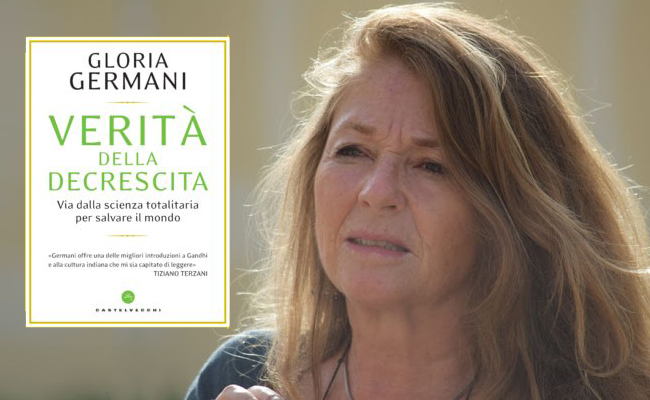

Gandhi, starting from the basics of Hindu culture, was able to give us ante-litteram lessons in degrowth, nonviolence, pacifism and deep ecology. We talk about this with Gloria Germani, an ecophilosopher who has always been committed to the dialogue between West and East, a student of philosopher Serge Latouche, Swedish ecologist Helena Norberg Hodge and journalist Tiziano Terzani, of whose thought she is among the foremost experts. Active in deep ecology movements, the Network for Deep Ecology, Navdanya International and the Association for Degrowth, she is a practitioner of Advaita Vedanta (Way of Non-duality), the best known of all the Vedānta schools of Hinduism. In 2002 she wrote the book Mother Teresa and Gandhi with a preface by Terzani who, being strongly interested in Gandhi in the last years of his life , said, “Germani’s book offers us one of the best interpretations of Gandhi that I have happened to read.”

The economy must be for man and not man subject to the economy. How did Gandhi envision the economy and what role did communities play? Self-reliance and self-production for an ecological way of life. What was Gandhi’s thinking in this regard?

For Gandhi, work must be done and built to ennoble man. There is a very famous quote by Gandhi from the 1940s that is worth quoting. “I oppose the ‘madness’ of the machine, not the machine as such. The madness concerns the so-called labor-saving machines. Men continue to ‘save labor’ until thousands of individuals are out of work […] The machine today serves only to get the few on the backs of the multitudes. The impulse behind this is not to save labor for the sake of men, but greed. I fight with all my strength against this state of affairs” . Today, when a handful of people own the wealth of half the world’s population, and given the relentless advance of robotics, Gandhi’s position is very forward-looking. It is fully in tune with many back-to-nature, environmentalist and ecologist movements.

Fritz Schumacher – the European economist who most echoed Gandhi – argued in 1975 that “if people are considered more important than goods, there is a tendency to maximize work and not production. The goal, then, becomes that of offering everyone the opportunity to work, both to develop their own skills, and to overcome the natural self-centeredness by working with others in view of a common goal, and, finally, to also provide the goods and the services necessary for existence”. This kind of economy is called one of permanence and not of growth. Gandhi’s vision was very articulated and coherent if we care to go deeper into it, although it is in complete antithesis to the concepts of the modern economy. The social system that the Mahatma hoped for in the aftermath of independence from Great Britain was Sarvodaya, literally “the service of all”. Each individual was supposed to act solely in the service of all other human beings within small local communities, i.e. by preserving and sustaining India’s 700,000 villages. This service would naturally flow into the “common good”. The “Service to all” works together with the other three pillars: “strength of truth” (Satyagraha) or non-violence towards not only other men but also nature and the ecosystem; “the love and preference for local materials and local craftsmanship” (Swadeshi); and “self-government or independence” (Swaraj). The latter, as we have already seen, is first of all the manifestation of control (raj) of self (swa) and of one’s ego passions, and only then can it become political self-government and national independence.

All of this is exactly the opposite of “modern economic science”, according to which society is based on individual selfishness and on Hobbes’ Homo homini lupus ( the human is like a wolf to other humans), that is, on an essentially predatory and violent conception of man. As Serge Latouche also demonstrated especially in his The Invention of the Economy, these ideas were born only between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including the concept of the single individual which did not exist before. In Europe everything was changing with the advent of Cartesian-Newtonian science. The most famous name linked to the birth of the new “economic science” is that of the Englishman Adam Smith. Professor of law, «he applied the Newtonian concepts of equilibrium and laws of motion and immortalized them with the metaphor of the “invisible hand” of the market which, according to him, would guide the selfish interest of every entrepreneur, producer and consumer, giving rise to what he called “the natural harmony of interests”» . Therefore a system made up of selfish individualisms in the search for one’s own self-interest would have been transformed into a harmonious whole for everyone.” . It is a law of which today we perceive all the groundlessness and misplaced optimism. In those years, an ethical reversal of epochal significance was in fact taking place in the West. Private vices were no longer vices, but became virtues that contributed to public wealth, as highlighted by Bernard de Mandeville in his The Tale of the Bees: private vices and public virtues. If today we are faced with the greatest challenge that humanity has faced – climate collapse – with the massive abuse of the earth, we must understand this predominant vision that has allowed us this abuse and rationalized it”.

We should realize that the non-dualist worldview produced the economy of permanence while the materialist and reductionist view produced modern economics, independent and separate from all the rest of life, with the myth of growth.

For these reasons, Gandhi is very current today. His positions make much more sense today for us Westerners than they did 90-70 years ago when we hadn’t yet sobered up over science and technology and the mirage of goods they would produce.

In unsuspecting times, Gandhi had understood the modern dangers of the pervasiveness of the consumer society and the production of futile things. What is the philosophy of the limit and what does it consist of?

This is an extremely important point on which we need to dwell (I dedicated the entire Chapter IV of my book to this). Gandhi puts it very well as early as his 1909 book that we have already mentioned. “The mind is a restless bird: the more it has, the more it wants to have and still remains dissatisfied. The more indulgent we are with our passions, the more unbridled they become. Our ancestors therefore put a brake on our indulgences. They saw that happiness was, to a large extent, a state of mind. A man is not necessarily happy if he is rich, or unhappy if he is poor.” writes Gandhi.

This is a common theme in Buddhism as well. The Second Noble Truth tells us that the cause of suffering is desire, the striving for something outside of ourselves. In fact, if we start from the truth common to Eastern thought that everything is impermanent and everything is interrelated, the tendency of the human mind to believe in words and in multiple phenomena leads us astray. When the Buddha realizes that all things have no substance, but pass away and become something else – he realizes that suffering lies precisely in the attachment to things, in the desire to stop them. This applies to people, social statuses (I’m an engineer, I’m a banker, I’m rich) properties (I have a house, a car), but also and above all for one’s ego, which like everything else, has no substance of its own but comes and goes. Morbidly clinging to one’s own survival is in fact considered a serious obfuscation that prevents us from seeing our true reality.

Modern thought, which was born in the West, has instead built what I call the Factories of the Ego.

The industrial society, the consumer society, must necessarily see what it produces and to do this it must advertise. Which means creating desires that don’t exist and thereby continually sowing unhappiness. The principle of marketing and advertising is in fact to “create a need that was not there before”.

Descartes – the father of modern philosophy – established the separation of the ego and the external world ( Cartesian dualism). With an argument that, to Eastern eyes, would have appeared as a major error, he justified and exalted the ego. And it is precisely this ego that is glorified through the marketing principle. Indeed, it is precisely through the phenomenon of desire that the Ego is solidified and crystallized, through a continuous process of dissatisfaction. As Girolamo Savonarola predicted several centuries ago, today we find ourselves immersed in the ” vanity fair.” Instead, the goal is to silence the psychological ego in order to reach our deepest silent essence, which coincides with the undivided essence of the universe. It may be called atman in Hinduism, or anatta in Buddhism, but the goal is the same: to orient [ourselves] toward a very high level of empathy with every living being of the past, present and future. “I” am a process, contiguous with other processes – in minds, bodies and matter, everywhere – that condition me and that I in turn condition. It is the relationships that matter, so the essential thing is to work for the harmony of the whole. The child must be nurtured by loving parental care, [and] only then, when he is an adult, can he work generously for the welfare of others and the harmony of the whole.

Instead, the industrial system, in addition to the predatory and competitive view of man, implies that it is right and proper to change the supposedly inert external matter. This premise has also been completely discredited by quantum physics, as well as by Eastern philosophies. Moreover, the industrial system cannot sustain itself without publicity. In summary, ego factories and manipulation of matter are the two great errors of modern society. No wonder the malaise is increasing exponentially both ecologically and socially/existentially.

As Gandhi says in a very clear passage,” The peculiarity of Hinduism is the unity of all life and this ensures that man is not the lord of creation. When we speak of the brotherhood of human beings, we think instead that all other lives are there to be exploited for human purposes. On the contrary, Hinduism excludes exploitation. To truly realize unity with every life form is not easy, but the immensity of our purpose places limits on our needs. As is evident, this is the opposite of the position of modern civilization that says, “increase your needs.”

You cite the philosophy of limit – very fashionable today – but I do not think this definition is appropriate. Because limit presupposes an ego that must limit itself, whereas in Indian culture and in Gandhi the goal is always the overcoming of the ego, because this overcoming is the only source of true happiness and true freedom.

For Hinduism and for Gandhi the way is to “free oneself from all lower feelings, that is, from attachment, from desire-hatred, from jealousy” , while as F. Schumacher clarifies: ” At the basis of every economic attitude, there is avidity, greed, envy, the lust for power. These are the real causes of war, and it is pure illusion to try to lay the foundations of peace without first removing them. It is doubly illusory to think of building peace on economic foundations, because these in turn are based on systematically cultivating the greed and envy that lead humans to conflict.”

In India, Gandhi is considered the Father of the Nation. Do you think contemporary India, with Modi’s nationalism and 9% annual economic growth, has forgotten the Mahatma’s inspiring principles?

It certainly has. We can say that already his disciple J. Nerhu, India’s prime minister since 1947, departed from Gandhi’s economic directions to largely follow a modern Soviet model. We must grasp, however, that the issue is more complex and global. This was well understood by Terzani who lived in and studied Asia for thirty years, from 1970 until his death in 2004. He had observed ” the missionaries of materialism and economic prosperity[…]; businessmen, bankers, experts of international organizations, UN officials, all convinced prophets of “development” at any cost.””, “One after another, the various countries of Asia ended up getting rid of the colonial game and putting the West at the door. But now? The West comes back in through the window and finally conquers Asia no longer by taking possession of its territories but of its soul. Now It does so without a plan, but thanks to a poisoning process against which no one has yet found an antidote for: the idea of modernity. We have convinced Asians that only by being modern can one survive and that the only way to be modern is our way: the Western way.

This is the process of globalization, which has been so well analyzed by Helena Norberg Hodge. It is not at all a natural evolution, as the historical narrative would have us believe. Rather it is the materialist view that is imposed through internationally passed Deregulation laws and through financial pressures. This diabolical combination ensures that no country can independently manage its livelihood and independence – as Gandhi intended.

What is the common thread linking degrowth, nonviolence and vegetarianism in Gandhi’s thought?

The cultural movement of degrowth was born around 2002 as a critique of modern economics and its underlying law, which is that of infinite growth (even though we live on a finite planet). As its leading exponent, Serge Latouche, recently reiterated, it was born as a synthesis of two cultural movements: that of the critique of so-called Third World development and that of ecological thought.

As I hope I have made clear, Gandhi is one of the greatest authors of the critique of Third World development through his sharp critique of modern civilization brought by the British to India.

He also refuted – with breadth of argument – the modern economy. His is an economy of permanence, based on small communities, irreconcilable with the ideas of individual profit and shareholder return taught in business universities today.

And we come finally to the theme of nonviolence – which Gandhi considered the very basis of Hinduism.

Through the discussion I have tried to propose, we can see well how nonviolence is the very basis of ecological thought. It stems from the certainty that everything is one and therefore not only concerns relations between human beings (between different human positions), but concerns all spheres: thus relations with nature, with animals, with all sentient beings, even with minerals and other inorganic substances.

This view is the same as what we now call Deep Ecology. Indeed, it is no coincidence that vegetarianism has been one of the foundation stones of Hinduism since time immemorial. The importance of vegetarian, organic, locally produced food (not imported from distant places) is central to Gandhi and to Hinduism in general, which has devoted a thousand-year tradition to it. The sacredness of the cow, which is so ingrained in India, far from being something primitive, is symbolic of the profound certainty in the interconnectedness of the whole, in the unity and sacredness of all that lives.

Gandhi writes, “The central fact of Hinduism is the protection of the cow. To me, it is one of the most wonderful phenomena of human evolution. It takes man beyond his own species. We enjoy the sight of the cow to realize its identity with all that lives. It is obvious to me why the cow was chosen as the quintessential symbol. In India the cow was the best companion in life. She was the bringer of abundance. Not only did she give milk, but she made agriculture possible. She is the mother of millions of Indians. The protection of the cow means the protection of the whole silent creation of God” .

I think Gandhi’s lesson is vitally important today for ecological movements, for Fridays for Future or Extintion Rebellion (Extinction Rebellion), for pacifists and for degrowth or growth objectors. As Tiziano Terzani reiterated only 20 years ago, Gandhi’s nonviolence is the only way out of a spiral of violence that has been increasingly manifested in the last 30 years, both in current wars and towards the Ecosphere with the dramatic climate crisis.

In a nutshell, today we must understand that peace and nonviolence are possible only in a context not dominated by Modern Economics, that is, in a worldview not based on dualism (with its corollaries materialism and mechanism).