The Malvinas Islands Question, understood as the sovereignty dispute over the Malvinas Islands, South Georgia, South Sandwich Islands and the surrounding maritime areas, originated on 3 January 1833 when the United Kingdom, breaking Argentina’s territorial integrity, illegally occupied the islands and expelled the Argentine authorities, preventing their return and the settlement of Argentines from the mainland, as well as bringing British subjects to populate the islands.

by Aram Aharonian

The Falklands are Argentine. The Malvinas are Latin American. And not of the British Empire. 190 years ago, on 3 January 1833, the Malvinas Islands were illegally occupied by British forces who evicted the Argentine authorities legitimately established there.

“Argentina, Argentina!” was the chant that echoed across several football pitches in Argentina this past weekend as tribute was paid to former combatants on the Day of the Veterans and the Fallen in the Malvinas War. But that same cry was heard, this very second of April, in the small Scottish town of Dingwall, 12,000 kilometres from Buenos Aires and a few thousand more from Port Stanley, capital of the Falklands.

It was when Ross County hosted historic Glasgow Celtic in the Scottish League. The visiting fans shouted for Argentina in their team’s victory because of the goal scored by Alexandro Bernabéi, a young defender who not only made history by being the first Argentinean to score a goal in a Celtic shirt, but also for being the architect of getting people in the United Kingdom to sing for Argentina on a symbolic date for the sovereignty of their country.

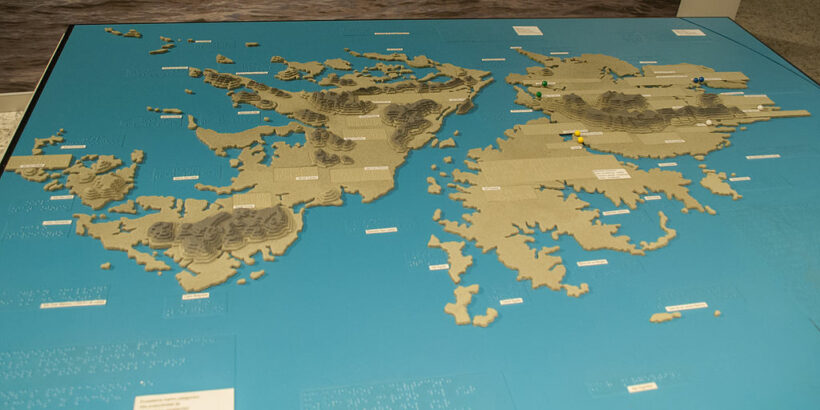

It’s a pity that Argentina’s national football shirt, which now sports three stars (for the World Cups won), doesn’t also bear the Falkland Islands logo! This year marks the 41st anniversary of UN General Assembly resolution 37/9, adopted on 4 November 1982, months after the end of the South Atlantic conflict, which did not change the nature of the sovereignty dispute, as this resolution demonstrates. In it, the UN once again requests the governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom to resume negotiations in order to find as soon as possible a non-violent solution to the sovereignty dispute over the Malvinas Islands and asks the Secretary-General to undertake a renewed mission of good offices to assist the parties. The Malvinas Islands formed part of the area under the jurisdiction of Spain since the entry into force of the first international instruments delimiting the “New World” shortly after the discovery of 1492. The Malvinas Islands were discovered by members of Magellan’s expedition in 1520. The Malvinas Islands Question, understood as the sovereignty dispute over the Malvinas Islands, South Georgia, South Sandwich Islands and the surrounding maritime areas, originated on 3 January 1833 when the United Kingdom, violating Argentina’s territorial integrity, illegally occupied the islands and expelled the Argentine authorities, preventing their return and the settlement of Argentines from the mainland, as well as bringing British subjects to populate the islands. Since 1982, the United Kingdom has denied the transfer of arms to the South Atlantic during the war. It was not until 2003, 21 years after the war, that the British Ministry of Defence published a report mentioning that the force that was set up to go to the South Atlantic during the 1982 conflict included nuclear-armed ships. At the time, the UK denied that it had violated the Treaty of Tlatelolco and claimed that all weapons were returned to the UK in good condition. Argentina protested strongly. Moreover, Declassified UK, a British portal specialising in defence matters, reported last year on the sending of British ships with 31 nuclear weapons to the South Atlantic conflict in 1982, at the no end of the bloody civil-military dictatorship that left the country in ruins, 30,000 people disappeared and the dream of recovering the Malvinas Islands turned into a nightmare. Argentina’s claim to sovereignty over the Malvinas Islands is not the only pending request for decolonisation in the world: 17 territories are currently being monitored to put an end to colonialism on a global scale. The Malvinas Question has been described by the United Nations as a special and particular case of colonial decolonisation, where there is an underlying sovereignty dispute and therefore, unlike in traditional colonial cases, the principle of self-determination of peoples is not applicable.

The British refusal to comply with the obligation to resume sovereignty negotiations is compounded by the continued introduction of unilateral acts by the UK. These actions include the exploration and exploitation of renewable and non-renewable natural resources – which Argentina continuously rejects – as well as an unjustified and disproportionate military presence on the Islands.

At 9 a.m. on Friday 11 June 1982, a Pope set foot on Argentine soil for the first time. John Paul II arrived in Buenos Aires for a visit of just under 48 hours in dramatic conditions for Argentine society: the Falklands War was in its no end. Many did not know it, and the triumphalism of the dictatorship took care to conceal it through propaganda, but the surrender was a matter of days away.

In fact, the surrender of Puerto Argentino took place two days later after Leopoldo Galtieri’s farewell to Karol Wojtyla at Ezeiza International Airport.

In 2015 photographs of Pope Francis holding a sign requesting dialogue between Argentina and the UK over the islands generated controversy on both sides of the Atlantic. Years earlier, the then Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, Archbishop of Buenos Aires, celebrated many masses on each anniversary before veterans of the war. In the 2008 craft he noted that “the conflict is a dark part of Argentine history that only acquires light from the courage and bravery of those who fought there”.

He stressed that “the drama of those who fought and returned from Malvinas is our drama because it puts us in front of our indifference and lack of love. Our elitist Style of Life rejects failure, devalues it or hides it; it does not allow itself to be taught from it (…) There is a ‘historical debt’ that will only be settled when every 2nd of April (…) is a reason for reflection, for affirmation of national identity and work for peace; only then will the blood of the 649 fallen not have been shed in vain”.

In Memoria del Fuego, the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano pointed out that “The Malvinas War, a patriotic war that for a while united the Argentinians who stepped on and the Argentinians who were stepped on, ended with the victory of the colonialist army of Great Britain”.

“The Argentine generals and colonels who had promised to shed every drop of blood have not even made a dent. Those who declared war were not even there for a visit. In order for the Argentine flag to fly in these ices, a just cause in unjust hands, the high command sent to the slaughterhouse the little boys hooked by compulsory military service, who died more from the cold than from bullets,” he added.

And he concluded: Their pulse does not tremble: with a sure hand they sign the surrender of the rapists of tied-up women, the executioners of unarmed workers.

As I said at the beginning: The Malvinas are Argentinean. The Malvinas are Latin American. And not of the usurping British Empire.