Armando Robles Godoy is, without a doubt, the most influential and creative Peruvian filmmaker of the national seventh art. He was born in New York on 7 February 1923, son of the great Daniel Alomía Robles, and came to live in Peru at the age of 10. In our country, from a very young age, he began as a writer and later as a film director, creating beautiful films, testimonies of the greatest artistic courage, such as “En la Selva no hay estrellas” (1967), which won the Gold Medal at the Moscow International Film Festival, “La Muralla Verde” (1970), which won the Golden Hugo at the Chicago Film Festival and “Espejismo” (1972), which to this day is the only Peruvian film nominated for the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Film.

By Sol Pozzi-Escot

We talked to Marcela Robles, his daughter, a great poet and journalist, about her way of conceiving Armando’s legacy, which we remember today, 100 years after his birth.

What is your first childhood memory of Armando?

I remember when he used to rock my sister Delba and me, still very young, on a swing that he himself had improvised with a board and a rope in the house of pona and bamboo where we lived. He even sang songs to us while he did it. Who could forget that. And I also remember seeing him sitting for hours at his little typewriter, in what seemed to me a kind of secret and mysterious ceremony that was not to be interrupted.

During those early years, you lived in Tingo Maria. What can you tell us about those years?

They were wonderful years. When I look at the photos, they really look like scenes from a real-wonderful film, which is why whenever I see “La muralla verde” I get a double thrill: the thrill of good cinema and the thrill of seeing a part of our lives reproduced. Although, of course, as a teenager I learned from my parents about the immense difficulties they had to face at that time, which were many. But in my childhood memory remains the memory of having spent those early years with an extraordinary freedom, in the midst of nature, because we were like explorers in a kind of paradise, although also exposed to the dangers of the jungle.

I don’t know if this is an idealised memory, but I don’t think I’m wrong.

Black and white group picture: On the left Mario Robles, his wife Lily, on the far right, Armando Robles with Ada Rey, his wife. Below, the children, Delba Robles, Marcela’s sister, Mario’s son Kurwenal, and on the side Marcela, with family friends, the Velasquez brothers, in Tingo Maria, 1955.

Black and white group picture: On the left Mario Robles, his wife Lily, on the far right, Armando Robles with Ada Rey, his wife. Below, the children, Delba Robles, Marcela’s sister, Mario’s son Kurwenal, and on the side Marcela, with family friends, the Velasquez brothers, in Tingo Maria, 1955.

You have also worked in Armando’s films, what was the atmosphere like on the film sets?

I was very young when I started working with him, and I had no experience, so I had to learn as I went along. It was scary at first because the whole crew was extremely professional and I felt I had to be up to the task: it was a very valuable and enriching process in every way. I didn’t just learn how to make films, I learned a lot about life itself. Armando imposed an order that, although it sometimes seemed disruptive, worked. I only knew that we had to follow directions, even if it was grudgingly, and that we had to work like crazy, because everything was crazy! But at the end of the day, I understood that if we didn’t impose that order it would have been total chaos. Many times, before filming a sequence, Armando would talk at length with Mario, his brother, who was the director of photography (extraordinary, by the way). Sometimes they would decide between the two of them, or share suggestions on how to do it. But if Armando had doubts about something (which I’m sure he did, like every filmmaker) he didn’t show it, and the crew felt that we were in good hands. Of course, as in any filming, there were huge messes, huge ones, but in the end everyone would calm down and shut up.

As time went by, did your way of understanding and approaching your father’s work change?

Definitely. There are films that “age” well (or don’t age at all), and stand the test of time, and others not so much. They lose charm, brilliance, validity. Armando’s films have not only remained relevant, but have grown over the years. And in my case, this is also due to the fact that I used to watch his films with a highly critical look. Now I just enjoy them. Perhaps also because of the knowledge, love and admiration I have developed for cinema in general and his in particular.

We know that you were a writer as well as a filmmaker. How would you characterise his work as a writer? What differentiates Armando the filmmaker from Armando the writer?

I think my father was a writer by nature. And he continued writing almost until the end of his days. And then I would see him writing no longer on his little machine at the beginning but on a computer that he never quite mastered. So, his literary and cinematographic vocation developed in parallel. He loved literature as much as film and for him they were two different universes expressed in different languages. He was a great reader. He started writing at a very young age, but he only began to publish in 1952, at the age of 29, when he took the courage to send his short story “Los tres caminos” to a competition organised by the newspaper La Prensa and won first prize, 13 years before he made his first feature film, although he had already made several short films. Other stories followed, some of which also won prizes: “El rabión” (which is formidable), “La muralla verde”, “En la selva no hay estrellas”, among them. The latter two, as we already know, were later made into the films of the same name. “La muralla verde y otras historias” brings together a large part of all these stories and was published in 1971, and republished in 2022 by Penguin Random House, Alfaguara, in a beautiful edition. It is a beautiful book. Then came his novels, “Veinte casas en el cielo” and “El amor está cansado”. It was precisely in La Prensa, where he worked, that he began to write film criticism. That was the beginning of his career as a filmmaker.

Among all your films, which is your favourite and why?

As I mentioned, I enjoy all his films now. But if I had to choose (happily I don’t have to) I would probably choose “La muralla verde” and the short film “El cementerio de los elefantes” (a real gem, Silver Hugo at the Chicago Film Festival in 1973), where I worked as assistant cameraman, and in which Carlos Ferrand was the director of photography. But I confess that I have a special weakness for “In the jungle there are no stars”, and I have the impression that nobody has “discovered” it yet”. I would say it is my favourite.

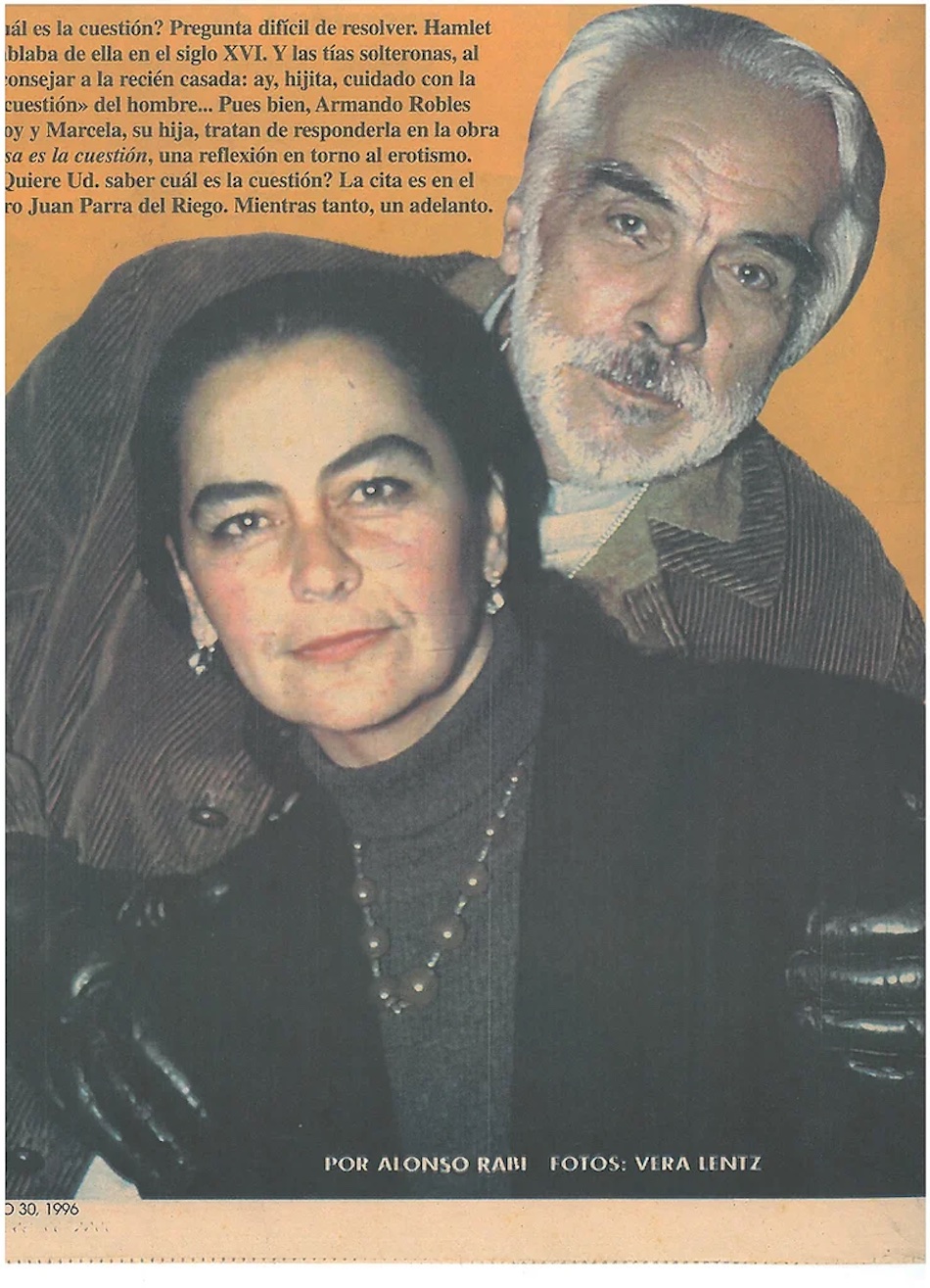

Marcela and Armando (1996), at the presentation of “Esa es la cuestión”, a play by Marcela directed by Armando.

Marcela and Armando (1996), at the presentation of “Esa es la cuestión”, a play by Marcela directed by Armando.

In an interview, Armando said he wasn’t afraid of death. How do you interpret that statement? Did he know that his work is immortal?

There’s really nothing to interpret. He simply wasn’t afraid of death. It was a frequent topic of conversation at our family gatherings, which sometimes included dear friends who are no longer with us. I think he managed to make himself an accomplice in his own death and often said it out loud at these gatherings: “I’m dying”. At first, we thought it was some kind of metaphor (we’re all going to die), and when we realised he was serious it was too late. Not for him, because he was totally ready to go. I have no doubt about that, if he knew his work was going to live on? He didn’t think much about it. He was proud of everything he had done and at the time he lived it with the passion and dedication that characterised him. After that he moved on to his next project. Unfortunately, the last one didn’t come to fruition. It was a kind of book of memoirs that he began to write with his brother Mario, also a writer and filmmaker. It would have been a happy no end, don’t you think?