“We shall overcome”. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

On the occasion of the anniversary of the birth of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (15-1-1929) and the World Day for African Culture and People of African Descent, the Costa Rican Wesleyan Methodist Church, IMWC, wishes to highlight the figure of this distinguished Negro pastor, defender of the rights of African Americans, and to celebrate his life and legacy by declaring ourselves against racism, poverty and imperialism.

Although Dr. King’s name is known around the world, many do not know that he was born Michael King, Jr. in Atlanta, Georgia, on 15 January 1929. His father, Michael King, was a pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. During a trip to Germany, King Sr. was so impressed by the story of Protestant Reformation leader Martin Luther that he not only changed his own name, but also that of 5-year-old Michael.

Martin Luther King, Jr. studied theology at Boston University. As a young man, he became aware of the situation of social and racial segregation in which people of African descent in his country, and especially in the southern states, lived. He became a Baptist pastor in 1954 and took charge of a church in Montgomery, Alabama.

Part of his legacy can be summed up in the following statements (in bold):

Struggle for change through non-violent protest. Inspired by Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi, Dr. King often referred to this kind of struggle as “the guiding light of our technique of nonviolent social change”.

Thus, King adapted and developed Gandhi’s concept of non-violence, which he creatively applied in a series of anti-segregationist campaigns that made him the most prestigious leader of the American civil rights movement. It also earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, at the age of 35, and his subsequent assassination by a racist bigot in 1968.

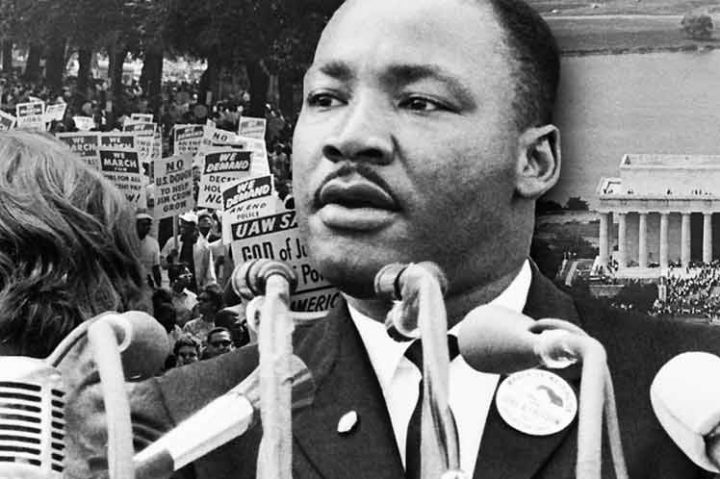

King’s non-violent action mobilised a growing portion of the African-American community, culminating in the historic march on Washington in the summer of 1963, which drew 250,000 demonstrators. There, at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial, Martin Luther King delivered the most famous and moving of his splendid speeches, known for the formula that spearheaded the vision of a just world.

I Have a Dream. Part of this speech-message reads: “One hundred years ago, a great American, under whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree appeared as a great beacon of hope to millions of slaves who had been branded with the fire of gross injustice. It came as the jubilant dawning of the long night of their captivity. But a hundred years after, coloured America is still not free.

This sermon is considered a masterpiece of oratory; in it, Martin Luther King raises to the status of an ideal the simple materialisation of equality: “I dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin, but by the qualities of their character”. Valuable as much for its condensed expression of principle as for its impressive emotional heights, this speech remains relevant and moving more than half a century after.

Another of King’s famous speeches, entitled Time to Break the Silence, is more combative and, for this very reason, has been silenced by official history. This speech was delivered at Riverside Church, New York City, on 4 April 1967. In this case, King presented a more revolutionary version than many Americans are willing to remember, making harsh criticisms of the Vietnam War and the country’s economic and social inequalities.

For the official memory, the speech, Time to Break the Silence, is rather uncomfortable, as in this sermon King showed his most subversive version, the one that cost him his life. In it, Dr. King spoke on behalf of the “poor of the world” and confronted the great powers that be by asking: “What do the peasants think when we ally ourselves with the landlords and refuse to put into practice our words about agricultural reform? The speech was in tune with King’s planned “Poor People’s Campaign”, an occupation in Washington to protest against economic and social inequalities in the US and around the world. MLK himself recognised that this discourse and the new demands incorporated into the civil rights struggle generated consternation among people of African descent.

In turn, in this sermon, the Baptist pastor points out to Americans how distant they were from “godly principles”. He even goes further and vindicates a revolutionary Jesus Christ tolerant of different ideologies, exhorting: “Could it be that they don’t know that the good news of Jesus was for all men? Communist and capitalist, for their children and ours, for black and white, for revolutionaries and conservatives? So, what can I say to the Vietcong or Castro or Mao as a faithful minister of Jesus? Do I threaten them with death or do I have to share my life with them?”.

In relation to the war in Vietnam, King also questions in this same speech the Vietnam War and its supposed causes, claiming that it is easy to realise “that none of the things we claim to be fighting for are really involved”. He also calls it “cruel irony” to see whites and blacks fighting a war to defend a nation “that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools”. American moralism was never more exposed than in Time to Break the Silence. This version of King, unheard and forgotten, responds to a filtered memory of the African-American people.

Dr. King’s opposition to the Vietnam War became an important part of his public image. On 4 April 1967 (exactly one year before his death) he delivered a speech entitled Beyond Vietnam in New York City. In that speech, he willed the cessation of bombing in Vietnam. Dr. King also suggested that the United States declare a truce with the goal of peace talks and that a withdrawal date be set.

In relation to his idea of economic and social justice, Dr. King was moved to focus on social and economic justice in the United States. He had travelled to Memphis, Tennessee, in early April 1968 to help organise a sanitation workers’ strike, and on the evening of 3 April he delivered the legendary speech I Have Been to the Mountaintop, in which he compared the strike to the long struggle for human freedom and the battle for economic justice, using the New Testament parable of the Good Samaritan to underline the need for people to get involved.

Finally, the IMWC highlights part of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s historical and combative legacy as an example for young people, as an achievable utopia and a vision of equality and justice for all that continues to resonate today.

“I only want to do God’s will and He has let me climb the mountain and I have looked around me and seen the promised land”. Martin Luther King, Jr.