Part of the dynamic of Chilean municipal politics is that every time a councillor loses his or her subsequent re-election, we learn of pronounced deficits in the municipal coffers. Thus, we have emblematic cases of Virginia Reginato in Viña del Mar (17.5 billion), Cathy Barriga in Maipú (34 billion), Felipe Guevara in Lo Barnechea (1 billion), Karen Rojo in Antofagasta, so far, the only one convicted and on the run, currently detained in the Netherlands awaiting extradition. Once again, an RN mayor, Rodolfo Carter, is currently under investigation by the Comptroller’s Office for millionaire tenders with resorts and holiday centres.

All of them are in addition to the last known case of Raúl Torrealba in Vitacura, who even received envelopes with cash in his own hand from municipality officials. Fifty percent of the municipalities are in the process of investigating situations of possible corruption.

Unanimously, the plenary of the State Defence Council (CDE) joins as a plaintiff in the investigation of the Fiscalía Centro Norte against the former mayor of Vitacura, and part of his former circle of trust: Renato Sepúlveda, Domingo Prieto, Antonia Larraín and two accountants who allegedly issued false invoices, for embezzlement of public funds and tax fraud.

According to América Transparente’s executive director, Juan José Lyon, “Torrealba created these institutions that were legally constituted as a neighbourhood council (community, territorial and functional organisations), which are legally accountable to no one, buy what they want and allow them to operate secretly. That’s why we’re only just finding out, they escaped the control mechanisms of the public apparatus”. One of the things about these legal figures is that every year the municipalities transfer funds to them. How much? “1500 and 2000 million pesos, with Torrealba it was around 15 billion”. “We asked for this information, and they said that as they were created before, they are outside the transparency law. We have been working on this for more than a year and they have invested in lawyers and resources because something is being covered up, there are 5 billion every year and we don’t know what they are spending it on. We want to know who is working and who they have hired as a company”. (…) “We are talking about communes with high purchasing power. On the subject of creating these “neighbourhood council-type” organisations, this only happens in Las Condes, Vitacura and Barnechea”.

Much has been said about the “good administrators” that right-wing politicians, associated with the world of business and enterprise, are considered to be. But this news is no longer news, it will be a matter of waiting for a new municipal election to find out about new frauds and schemes to cheat the treasury and steal money from all Chileans. We also have the system that had officials of the commune of Las Condes, who through the use of “improper” ballots spent more than 60 million pesos in alleged overtime.

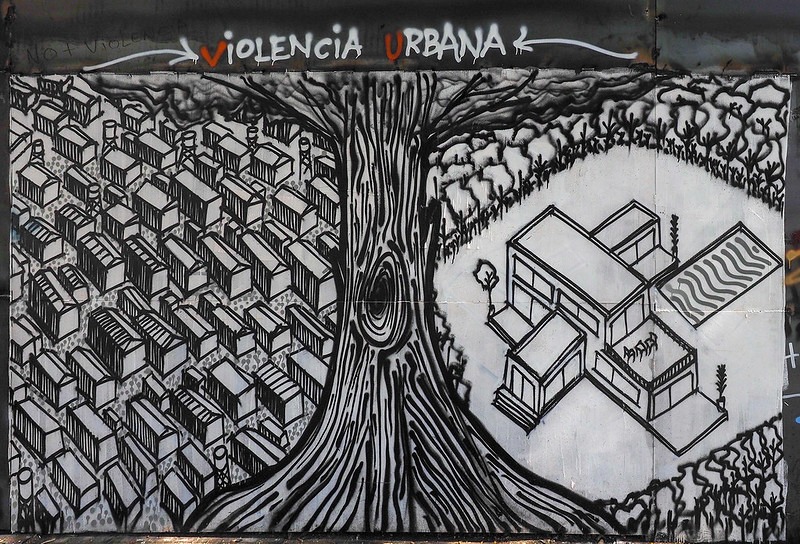

The municipalities are real “pay boxes” of the State. Large resources that should be destined to social rights such as health, education, security, housing or work are, in a criminal way, destined to the pockets of their administrators. And that is only counting the money removed in an irregular way, because if we were to count the “regular” cases of squares and pavements that are built and rebuilt every three years without any need, but with suspicious links to their owners. As the comedian Bombo Fica would say, “sospechosa la w…”.

The truth is, there is no column that can stand all the examples we have. That is why we ask ourselves; how can we guarantee management with principles of probity?

And although complex, the only response is the empowerment of citizens, the taking of sovereign control of local power by neighbours. In this instance, the one closest to the citizenry in politics, local government, real democracy must be born, and municipalities must become the head of organised neighbourhoods vis-à-vis the state, and stop being the tail of state power.

Collaborative writing by Rubén Marcos Velásquez; Sandra Arriola Oporto; Jorge Ortiz Guerra; M. Angélica Alvear Montecinos; Guillermo Garcés Parada and César Anguita Sanhueza. Political Opinion Commission