With Lula’s victory, many challenges lie ahead that we will have to observe and seriously reflect upon, the first of which is the transition of government that should only have to take place on 1 January 2023.

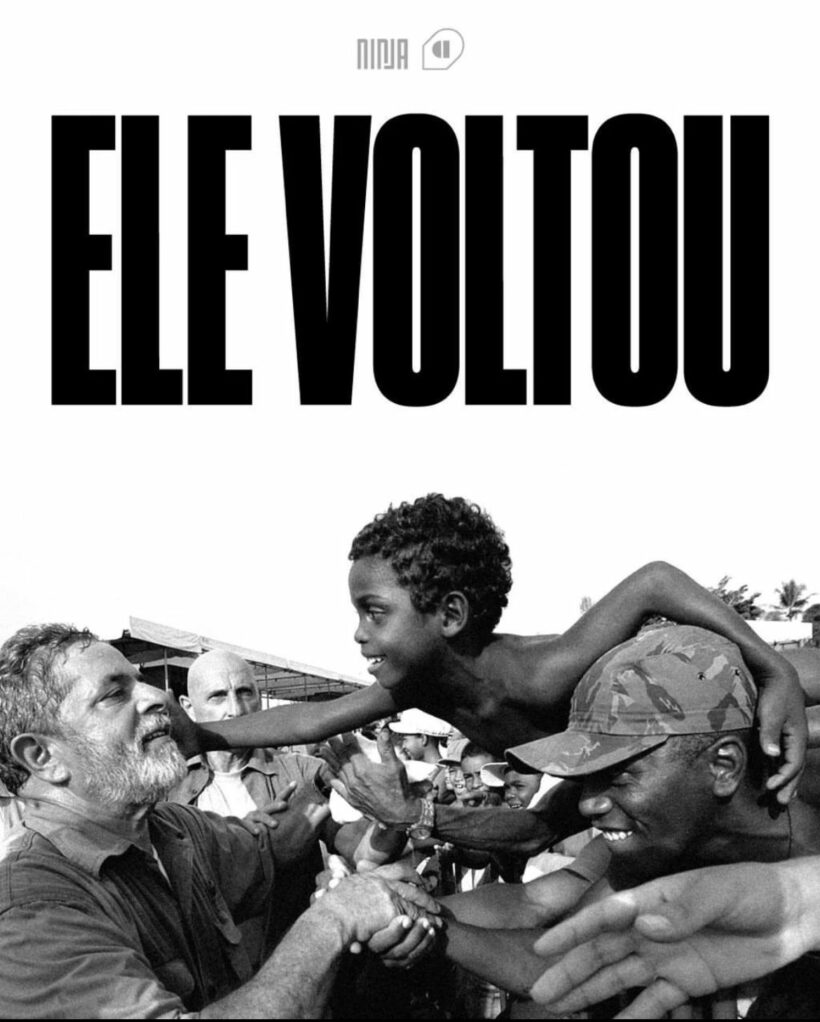

The page of the coup delivered in Brazil through the fraudulent impeachment process of Dilma in 2016 and the illegal imprisonment of Lula in 2018 is beginning to turn, but it is still too early to celebrate.

As much as love has defeated hate at the national level, we must be very cautious until the inauguration of the new government, because Lula’s victory was narrow, he lost in many states and there is great irritation in the sectors that support Bolsonaro’s militias.

Despite the support and public recognition that several world and national leaders have already declared for Lula’s victory, as far as Bolsonaro is concerned, the transition could be even more tumultuous than the Trump-Biden transition in the United States.

We have already had a small taste of this during the voting this 30 October 2022, when another unprecedented authoritarian measure took place, in which hundreds of police operations were carried out on roads and highways across the country to prevent, destabilise, delay and discourage the population from going to vote. Interestingly, most of these operations were carried out in the Northeast, where the majority vote was for Lula.

Moreover, the broad front for democracy led by Lula lost the gubernatorial elections in many important states, will have to govern with a polarised congress and deal with a very radicalised and conservative opposition.

But the most complex challenge for the Brazilian people will probably not be in the geopolitical, social or economic fields, areas in which Lula’s government already has a clear course and a certain command of the situation.

The most complicated challenge for the government and for the population will be the dispute over narratives in the cultural ambit and in the media. In this field we urgently need to promote humanist agendas, as the debate is dominated by fundamentalist opinion-makers of all kinds.

Communicators, pastors, police, politicians and influential people exploit misinformation to reinforce prejudices, launch hate speech and incite armed violence and political persecution against those who think differently.

With an increasingly narrow and fragmented mental form, much of the population has become hostage to fake news and eagerly awaits the next factoid to have an opinion, to vent their tensions, to feel part of something bigger and to find some meaning in collective life.

In the second round of these elections alone, we witnessed how a pro-Bolsonarist congressman and congresswoman recorded videos while making an attempt on the lives of policemen and a journalist. Visibly unbalanced, they not only took pride in their unbridled violence, but encouraged others to follow in their footsteps and commit hate crimes.

Contrary to what many might imagine, the elections were not greatly affected by these two violent episodes that occurred during the second round largely because of the fanaticism and fundamentalism that is intensely fuelled on a daily basis.

In this scenario of much misinformation, it is essential that we create new humanist referents and an “anti-fundamentalist” culture based on freedom of ideas and beliefs.

Even if Lula’s future government succeeds in governing and fulfils the economic promises of improving the material life of the population, cultural life cannot be left in the hands of the banks of the Bible, the bullet and the ox. Nor can we repeat the strategies of fundamentalists and neo-fascists; history has already shown where this can lead us.

With some humanist strategies in the face of setbacks, it is possible to confront the absurdities of these fundamentalist and conservative movements in a creative way, using the methodology of active nonviolence, organising local groups and installing another type of agenda, another type of aesthetic and another type of style on the political scene.

We, humanists from São Paulo, are exhausted and happy for having victoriously concluded such an arduous and difficult campaign, happy and grateful for having managed to change the narrative during the second round of the elections, for having convinced many artists and communicators to use their creativity and not play dirty like the adversary, happy for having inspired others to make a segmented and humorous communication that helped to break the fizz and reach other audiences that were still undecided.

At a time when the strategy of fighting fake news with more fake news was proving ineffective in changing public opinion, innovative public transport actions, videos, songs and creative materials began to emerge that managed to expand the campaign for democracy to different niches and audiences.

We don’t know if it was by “osmosis” or by “demonstration effect”, but once again we contributed to a picturesque phenomenon that Silo called the “fly in the balance”, and we made fundamental contributions in this final stretch of the electoral dispute, with a marked change of tone, colours and style both in the street actions and in the videos and materials published on the networks.

Now that the elections are over, it will be necessary to maintain a permanent campaign to win over the other half of the country. This is a task that we need to think about seriously and in conjunction with other movements, entities, institutions and organisations. If we leave a cultural void, this void will be filled by anti-humanist and retrograde forces that are articulating themselves internationally with increasing violence.

It is not enough for us to communicate images of the future full of possibilities, we need a simple path that ordinary people can follow and create extraordinary collective experiences.

And, far beyond contesting narratives or positions within a country, far beyond humanising a particular national culture, we have to learn to build the cultural matrices of our future universal human nation.