One of Gene Sharp’s most widely reproduced publications is his 1973 list of 198 nonviolent methods (or types of action). In 2021 Michael Beer published a study in which 346 tactics of nonviolent resistance are listed. These 148 types of nonviolent actions are 75% more examples of available actions to protest, claim, etc. Is the number the important thing? Well, it is an approximation that is not bad, especially because it seems to us to indicate that nonviolence is still alive, creative and adapting to changing times, a sign of good health.

By Pepe Ambrona/Nonviolent alternatives

The work we are reviewing today, “Tactics of Civil Resistance in the 21st Century” is 116 pages long and is published in 2021 by the ICNC (International Center for Nonviolent Conflict) and its author is Michael A. Beer.

The International Center on Nonviolent Conflict is an independent, non-profit educational foundation founded in 2002. It promotes the study and use of non-military strategies by civil movements to establish and defend human rights, social justice and democracy. Based in Washington, DC, ICNC works with educational institutions and non-governmental organisations in the United States and around the world to educate global audiences and influence policy and media coverage of the growing phenomenon of strategic nonviolent action.

Michael A. Beer is director of Nonviolence International, a Washington, DC-based non-profit organisation that promotes nonviolent approaches to international conflict. Since 1991 he has worked with NVI to serve marginalised people who seek to use nonviolent tactics often in difficult and dangerous environments. This includes diaspora activists, multinational coalitions, global social movements, as well as within: Myanmar, Tibet, Indonesia, Russia, Thailand, Palestine, Cambodia, East Timor, Iran, India, Kosovo, Zimbabwe, Sudan and the United States.

Introduction

Beer begins his work with a paragraph worth reproducing: “Nonviolent civil resistance occurs daily in many societies in a variety of forms including indigenous blockades against resource extraction in the Amazon, anti-corruption hunger strikes in Russia, street protests against dictators in the Middle East and North Africa, illegal same-sex wedding ceremonies in India, and whale protection interventions on ships in the Southern Ocean”. And the list of examples could be much, much longer, as he goes on to show.

Almost immediately he acknowledges that “Despite widespread interest in the subject, however, the most comprehensive effort to catalogue the wide range of nonviolent tactics remains Gene Sharp’s 198 nonviolent methods, an extensive list complete with descriptions, examples, and categories that was published in 1973 (Sharp, Gen. The Politics of Nonviolent Action, Part Two: Methods of Nonviolent Action. Boston, MA: Porter Sargent Publishers, 1973). Since then, there has been no comprehensive effort to meaningfully update this acclaimed list”.

And here we must make a small terminological point: In this monograph, the term “tactics” will be used interchangeably with the term “methods”. Here in Spain, we usually talk about types of nonviolent action.

Since 2016, Nonviolence International has been collecting and identifying new methods of civil resistance in the database of nonviolent tactics. This monograph emerged from this cataloguing process and answers three questions:

- What tactics did Sharp not identify and what new civil resistance tactics are there?

- What new categorisation of tactics can be useful for documenting and understanding this human activity?

- How can this new knowledge, about tactics and their classification, be useful for practice?

Ultimately: studying tactics can inspire and promote action, deepen academic understanding, help recover the history of nonviolence, improve skills through education and training, and improve strategic planning.

Civil Resilience

The monograph confronts the definition of civil resistance and opts for Veronique Dudouet’s definition in Powering to Peace: Integrated Civil Resistance and Peacebuilding Strategies (2017):

Civil resistance is an extra-institutional conflict resolution strategy in which organised grassroots movements use various […] nonviolent tactics such as strikes, boycotts, demonstrations, non-cooperation, self-organisation and constructive resistance to fight perceived injustice without the threat or use of violence.

It also reminds us that civil disobedience is not synonymous with civil resistance, but a tactic within civil resistance.

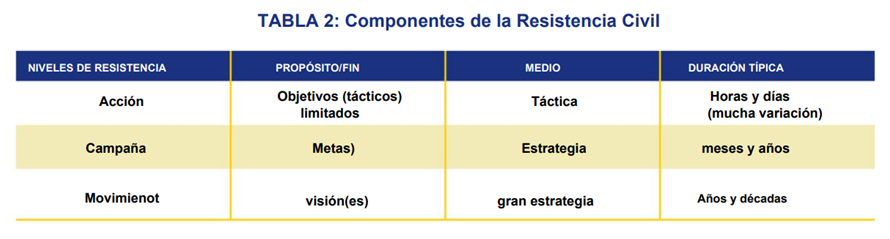

In order to better understand civil resistance, he resorts to categorising it into 3 levels: action, campaign and movement; as seen in the table below:

The use of one or several nonviolent tactics alone is often not enough to wage a nonviolent campaign. A strategy is needed, reflected in:

The use of one or several nonviolent tactics alone is often not enough to wage a nonviolent campaign. A strategy is needed, reflected in:

- Massive and sustained participation

- Resilience in the face of repression

- Effective selection of support networks

- Adherence to six key factors that make movements effective, including: unity, strategic planning, nonviolent discipline, growing participation, managing repression, and facilitating defections of allies from opponents in favour of the movement.

Classifications of nonviolent tactics

At the same time, Beer’s monograph offers a new classification of nonviolent tactics based on what is said, what is not done, and what is done, further divided by whether they are coercive or confrontational or persuasive or constructive.

There is a broken line between actions of protest and appeal to indicate that many acts of expression can be used for both constructive and confrontational purposes.

It is very useful for nonviolent reflection to have different models in order to compare the analyses of various authors and to be able to organise actions more consciously. Here is another way of categorising nonviolent actions:

Why types of nonviolent actions have multiplied.

According to Beer, the multiplication of nonviolent tactics is due to:

1.- Growth of digital technologies, which have enabled mass campaigns through digital platforms (e.g., Avaaz) that channel petitions or call for demonstrations. Anonymus would be another example of new nonviolent actions.

2.- Art-based cultural resistance, through art there have been actions to protest, appeal for justice, raise awareness, … For example, Beautiful Trouble (Boyd and Mitchell, 2016) is a book that highlights effective creative resistance tactics used in many campaigns. It was co-written by dozens of activists in the internet cloud and has an accompanying website, network and training group that seeks to promote effective and creative nonviolent action.

3.- Human rights activism, there are many grassroots organisations developing nonviolent tactics around the world to fight for human rights. One example is New Tactics in Human Rights, which disseminates tactics from various campaigns for use by other activists.

4.- Spreading knowledge about civil resistance. Although there is still a digital divide in many parts of the world, and digital surveillance and censorship are common practice, the internet has contributed significantly to the global spread of knowledge about civil resistance. Prior to the internet, efforts by scholars, educators and trainers to teach nonviolent resistance were limited to in-person interaction or phone calls, and the financial and logistical constraints that accompanied them. Improved access to the internet, both in terms of infrastructure and affordability, as well as advances in connectivity in many parts of the world, has allowed educators to explore less costly and more easily scalable educational avenues.

5.- Tactical innovation by women and sexual/gender minorities. Women pioneered many of the hundreds of non-violent methods that have been observed throughout history… Women activists have been able to capitalise on five sociological characteristics that gave them an advantage and a specific edge in civil resistance movements, compared to men: the presence of women reduces the level of violence and repression by security forces; women are often the best guardians of nonviolent discipline within the movement; women tend to organise in horizontal networks, which prove to be more efficient and resilient for a movement than hierarchical systems led by men; women show fewer internal rivalries and can often achieve greater unity than male activists; women show a greater ability than men to build solidarity bonds across and beyond social divisions (whether religious, ethnic or socio-economic) and political rivalries.

Resistance to the rise of global corporate power. Tactical] interventions occur in many places, from the point of destruction where resource extraction is devastating intact ecosystems, indigenous lands and local communities, to the point of production where workers are organising in the sweatshops and factories of the world. Solidarity actions arise at the point of consumption where products that are made from unjust processes are sold, and inevitably communities of all kinds take direct action at the point of decision making to confront the decision makers who have the power to make the changes they need. Another common intervention occurs at the point of transport in the form of blockades of ships, trains and other vehicles.

Ongoing repression. Authoritarian regimes routinely repress and retaliate against the independent actions of civil societies and are constantly inventing and experimenting with new means to do so. This authoritarian backlash tends to stimulate tactical innovation on the part of repressed but still mobilised groups. The authorities are not prepared for this. To minimise the costs and risks of being repressed, activists are encouraged to experiment with a variety of tactics of nonviolent resistance.

Competition for public attention. Nonviolent campaigns are set to compete with the mass media for information that reaches the public.

Competition for resources between groups within the same movement. Cunningham, Dahl and Fruge (2017) statistically analysed the diffusion and diversification of tactics used in self-determination struggles from 1975 to 2005 and found that: “Given limitations in their capacities, competition between organisations in a shared movement, and different resource requirements for nonviolent strategies, we show that organisations have incentives to diversify tactics rather than simply copy other organisations”.

10.- Natural or human-induced disasters. The COVID pandemic of 2020 is an example of a disaster that led to numerous tactical innovations. For example, KPop fans in Tiktok flooded the Trump campaign with requests for tickets to his rally in Oklahoma, to deprive his supporters of the opportunity to attend the rally and to deceive organisers about the number of attendees.

Assessment of the monograph

This monograph by Michael Beer provides a much more up-to-date and comprehensive list of tactics or types of nonviolent action. This alone would be inspiring for our social action. But it also shows us various analyses of civil resistance that can help us to understand the concept better and apply it more clearly. Finding time for personal and community reflection on our political action is crucial and very positive for the development of our actions. This document can contribute to this, and is therefore very suitable for calm, critical and self-critical analysis, and a call for imagination and creativity in our actions.

It is important to note that the monograph is of the opinion that not just any action can be considered a nonviolent tactic and, among others, the criteria it imposes are that in addition to being nonviolent, they should not be routine or institutional processes with known results.

So, we encourage you to consult the link and enjoy the extended list of nonviolent tactics.