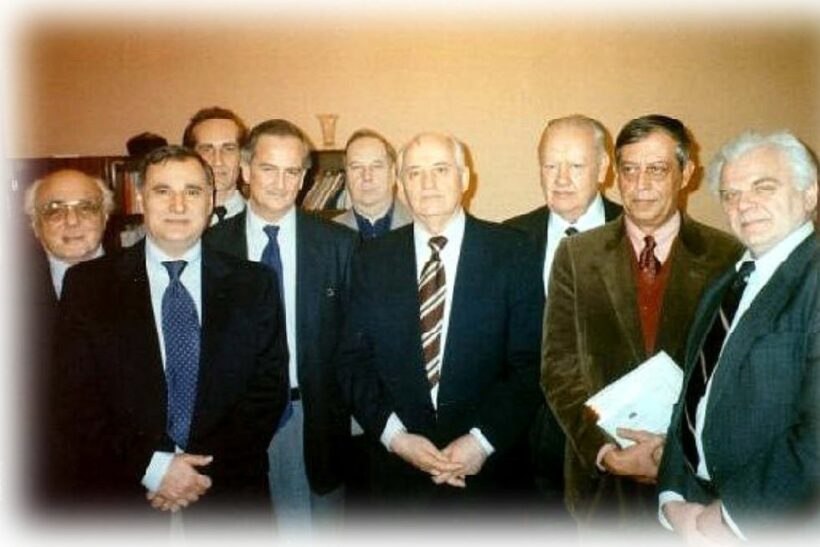

The last president of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, who died today in Moscow at the age of 92 after a serious and prolonged illness, was very close to Silo and the humanists, according to Russian state media. He maintained an open and constant dialogue with them during his years in power, meetings, encounters and explicit mentions in his 1997 book “Humanism and New Thought”, where Gorbachev notes:

“Coincidences in history are not a frequent occurrence, but they are found. In some cases as a result of chance, in others as a reflection of legitimacy. The coincidence to which we refer here is not only legitimate, but in a certain sense also remarkable.

It is that, at roughly the same time, around the 1980s, two trends in thought and practice, one might say, two philosophical-political phenomena, emerged: the Humanist Movement and New Thought”.

In his writings the President of the Soviet Union highlights this extraordinary convergence and ends by saying that “inspired by the ideas of Humanism and New Thought, we can, I believe, look to the future with optimism”.

His government became associated with the terms Perestroika and Glasnost (reform and openness), a reform that transformed his country’s politics and economy. Not only was he the last President of the Soviet Union, as his term saw the fall of the Berlin Wall and the break-up of the Soviet conglomerate, but also the end of the Cold War and the beginning of proportional disarmament among the great powers in order to secure peace. Many were indeed the efforts of this remarkable President to contribute to world détente.

After the collapse of the USSR, his stance towards the then President of Russia, Boris Yeltsin, was particularly critical. Gorbachev spent his early years in the post-Soviet era harshly questioning the reforms carried out by the new Russian leader, especially when he sought to increase his own powers and legitimise neo-liberalism.

Nobel Peace Prize winner, he attended the late 2009 Summit held in Berlin, Germany, where together with Mairead Corrigan Maguire, Lech Walesa, F.W. De Klerk, Muhammad Yunus and many others, he listened to Silo who in his speech said: “In terms of preoccupation with the issue of violence, we are notably behind schedule. I would like to say that the defence of human life and the most elementary human rights has not yet been established on a general and global level. There is still an apology for violence when it comes to arguing for defence and even “preventive defence” against possible aggression. And there seems to be no horror at the mass destruction of defenceless populations. Only when violence touches us in our civilian lives through bloody criminal acts do we become alarmed, but we do not fail to glorify the bad examples that poison our societies and children from their earliest childhood.

It is clear that neither the idea nor the sensitivity capable of provoking a profound repudiation and moral disgust that would lead us away from the monstrosities of violence in its various forms is yet in place.

For our part, we will make every effort to establish the relevance of the themes of Peace and Nonviolence in society, and it is clear that the time will come for individual and mass reactions. That will be the time for a radical change in our world”.

This was probably the field in which these two tendencies converged the most, in the sustained efforts for disarmament, peace and non-violent consciousness.