The world’s two most populous nations have a simmering border conflict that goes back decades and occasionally makes the news in the Western media. 24 soldiers were killed as a result of it in 2020. It would be less concerning if neither nation was armed with nuclear weapons, but sadly this is not the case and the fact that this tension lingers holds up the prospects for global nuclear disarmament. But how did this conflict even start?

It is not unknown that previously colonised countries still have to deal with problems created because of colonisation. The colonisers have long left the shores of these places, leaving the people to pick up the pieces of the issues that the colonisers created. The India-China border dispute is one such issue which could have been solved long back. It is not to say that the issue exists only because of how it was handled by the British, later on independent India’s government also bears some responsibility. But it can’t be denied that the seeds of the problem were sown way back when the country was under foreign rule.

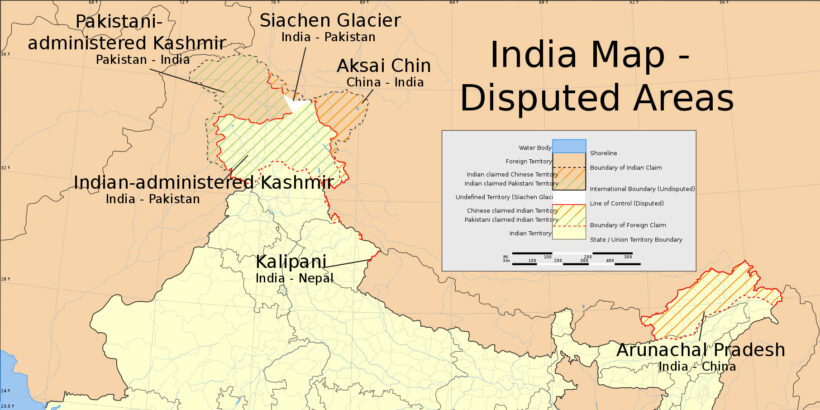

The border dispute emerged in the early 1950s when the People’s Republic of China staked its claim on Tibet, a move which created between India and China the longest undemarcated border in the world. But the ambiguity of borders between India and China dates back to colonial times. As reported in the E-International Relations, “The British initiatives to demarcate the Himalayan frontiers were guided primarily by its strategic competition with Russia…. In the western sector, the first attempt to fix a boundary line was taken in 1865.” Uncertainty regarding the border started in 1846 when the British overthrew the Sikh Empire and claimed authority over the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The state was then handed over to the Hindu Dogras who were in allegiance with the British, but the Dogras had no clear knowledge of where the border lay because of the constant fighting between the Sikhs, the Dogras, the Chinese and the Tibetans, with each trying to capture more territory. In the end, when the fighting stopped, no one new whose land ended where.

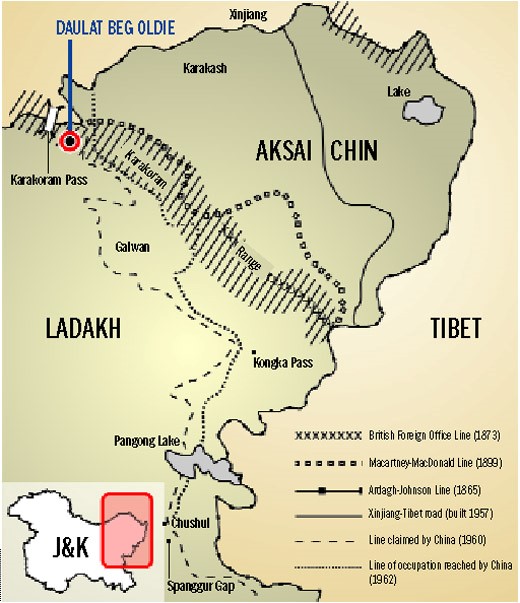

The first attempt to make an official border line was undertaken by Sir W.H. Johnson, the then surveyor General of India. He produced elaborate border claims stretching the Dogra state to the Kunlun Mountains and including all of Aksai China. This proposition was never fully accepted even by the British. The second came in 1897 by the director of British Military Intelligence Sir John Ardagh, who revived the Johnson Line as he believed it important to secure strategic leverage against Russia. This line then came to be known as the Ardagh Johnson line.

The horrendous matter is that between 1865 and 1897, the British seemed to be playing with different versions of the northern and north-eastern boundary of Kashmir depending on the threat from Russia. It shows how trivial was the border matter to them. The other important point to note is that none of these different border proposals were ever shown to China. The only one presented was the 1899 Macartney-Macdonald line but that was never officially accepted by the Manchu Dynasty then ruling China. Hence, the border uncertainty was allowed to fester to the point we see today. All the boundary options were informal. The British chose which boundary to use depending on its convenience.

So, it can be argued that the 1962 India-China war was a result of the British government’s non-committal towards the border, leaving the country in a state of flux as to what to do. India was dealing with so many internal issues at the time that came with being newly independent and the devastating conflict with Pakistan, that the border dispute was pushed down the priority list.

The eastern borders of India were left contentious because the British were satisfied by their occupation of the Brahmaputra plains, as extending jurisdiction to the mountains bore neither strategic nor commercial value. It was simply to delineate responsibility that “the foothills were divided by an outer line representing the external territorial frontier of the British Empire, and an inner line which was forbidden to cross without a permit.” (E-International Relations) this again was just an informal vague demarcation that continued.

In 1914 there was another attempt at resolving the issue. The British organised a conference in Shimla, India which was attended by the representatives of both China and Tibet. At the time China had a weak central government, giving confidence to the British that it would be easy to make China agree to their demands. However, China vehemently refused to accept the proposal, but the British went ahead and signed the agreement with a few Tibetan delegates anyway to bring into effect what is known as the McMohan Line. The line runs from the eastern border of Bhutan along the crest of the Himalayas until it reaches the great bend in the Brahmaputra River where the river emerges from its Tibetan course into the Assam Valley. (Britannica). Even after the signing, China never accepted this ad hoc border, maintaining that Tibet wasn’t an independent country and therefore had no right to decide the limits of its borders.

Even after all this, there was relative peace between India and China until 1960, when delegates from both nations met again. A Frontline article reported that, “The Chinese government offered to recognise India’s claim over the Arunachal Pradesh up to the McMohan line in return for India’s recognition of China’s claim over the Aksai China peninsula. Nehru rejected the offer and adopted an inflexible diplomatic posture on the border issue.”

It would be unfair to say the British are solely responsible for the dispute that exists today; Indian diplomats have their fair share of responsibility as well. But it cannot be denied who started it and who is paying the price today.

This article is one of an upcoming series in order to understand the India-China border dispute in its complexity and depth.