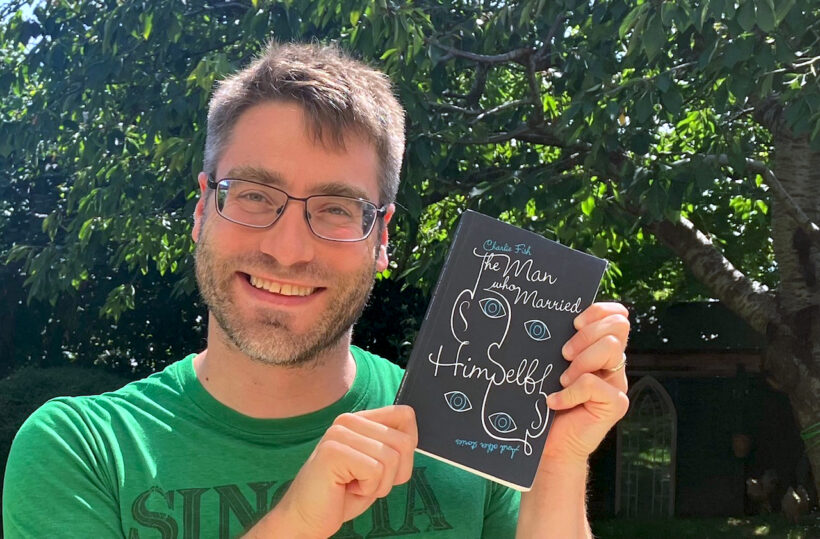

I had the opportunity to talk with Charlie Fish, an author, and editor, about his book, “The Man who Married Himself.” In part I of the interview, Charlie tells us how he started his Fiction on The Web magazine. “When I was a teenager in the 1990s the World Wide Web was making the Internet more accessible, and I saw an opportunity to create a platform for budding short story writers like myself. At the time there were very few places publishing fiction online, and we all supported each other.”

Charlie could have chosen and more traditional path for publishing his collection, but he says, “Publishing the collection via Kickstarter has allowed me to ignore commercial considerations and create exactly the book I wanted to make. Not only is the content compromise-free, but also copyright-free. Publishing the collection as a “Free Cultural Work” under a Creative Commons license is something traditional publishing would never have allowed.”

The book contains seventeen short stories, each one illustrated by Yvette Gilbert and accompanied by a short essay. Regarding the essays, Charlie explains, “Our experience of a piece can be hugely enriched by understanding how and why it was created. My stories are all very personal, and the opportunity to explain why they mean so much to me allows the book to represent me not just as a writer but as a person.”

To read part I of the interview, please click here.

JS: The collection presents a mixture of genres, some are very realistic, some are humorous, some are speculative, and others are philosophical. As a writer, what are the advantages you can see in publishing in this variety of tones? Did you envision any kind of audience?

CF: I’m not famous and I don’t make any money, which are great advantages because it means I can write what I like. I have many ideas; like a painting, each idea can be strengthened by giving it the right frame. I don’t always get it right. Many times I’m halfway through writing something and I know it hasn’t worked. But when I’ve pitched it right, I get very excited because I know that people will respond to the story regardless of its tone or style. If I “trick” someone who usually reads humorous stories into being moved by a piece of speculative fiction, all the better.

JS: One question I always have is why you chose a genre to write a story. For example, “Ship Psychiatrist” is a sci-fi story but it could be a story written as historical fiction, for example. How is that process?

CF: “Ship Psychiatrist” was inspired by an unusual combination of circumstances. First, a friend of mine told me that his colleague had created a science fiction universe with its own history and rules and internal logic. The two of them were collaborating to write a story based in that universe. I felt totally jealous, and so challenged myself to write an even better story set in the same universe.

At the same time, my dad found an old diary written by his father while serving as the ship doctor on the final transatlantic voyage of the famous passenger vessel RMS Queen Mary. I became captivated by the idea of a doctor responsible for the mental health of thousands of fragile people trapped on a boat, while privately suffering from his own mental ill-health.

The two concepts collided, and “Ship Psychiatrist” was born. As you can see, in this case the genre was baked-in with the conception of the story – and I think that’s usually the case.

Genre can be a bit of a red herring anyway. Genre is useful for writers because it creates limitations, and pushing against limitations is a wonderful formula for stimulating creativity. Genre is useful for publishers because it helps marry a story with its audience. And genre is useful for readers because it manages their expectations, and delights readers when those expectations are knowingly subverted. But genres are often blurred and combined; aiming to write in one narrow genre is dangerous because you must navigate a minefield of cliché.

JS: In “Go,” you write, “Western culture favours (sic) games like chess, where the object is to destroy your opponent, rather than go, where the object is to negotiate shared territory.” Tell me more about it.

CF: Go is an endlessly fascinating game. One of my work colleagues happened to be a dan-level player, and for years he tutored me once a week. Learning go felt more like reading Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, or Confucian wisdom, than playing a game.

I do think that the nature of our most ancient games reflects something about our collective culture. In the West games of domination like chess have always been popular, and the idea of a game as subtle as go, in which allowing your opponent swathes of territory is part of the strategy, feels very foreign.

JS: I remember exactly where I was when I read “The Cut.” I was in Williamsburg, in Domino’s park. Maybe because I’m a man I was afraid of reading the story of a man subjugated in a matriarchal society. What responses have you received to the story? Are those responses different from men to women?

CF: I was appalled to discover how many girls and women live with the effects of female genital mutilation, even in my own country. Infibulation is worse than torture, causing life-long suffering with no purpose or meaning other than the oppression of women. As is so often the case when something in the world upsets and angers me so much, and I feel utterly helpless to do anything about it, I resort to the one thing I can control: my stories. I wrote “The Cut” to raise awareness of this shocking practice, and I switched the genders because I especially wanted to make men squirm.

I got my wish at a reading in a Camden bookstore. I read aloud the part where the main character’s penis gets cut in half, and I enjoyed watching the audience – particularly the men – shift uncomfortably in their seats.

“The Cut” is the most serious and pessimistic story in the whole collection, and some people have called it out as their favourite, perhaps in part because it’s surrounded by light and funny stories so it hits you like a train you didn’t see coming.

JS: As for “The Cut,” I thought we might not have an escape. Either we live in a matriarchal society or a patriarchal society. Is it possible to create a dialogue between genders without establishing hierarchies between them?

CF: Naomi Alderman’s novel “The Power” makes the same argument, that we are doomed to choose between a patriarchy or a matriarchy, and each would be as toxic as the other. But that book also suggests it’s not necessarily about gender – it’s about power. That’s what I truly believe. We live in a society where power and gender are deeply linked, but they don’t have to be. We have made great strides with feminism, LGBTQ+ rights and representation, the #MeToo movement, and so on. But while the institutions of power – the super-rich, religion, politics, media, etc. – are dominated by men, we will never be able to overcome gender-biased hierarchies. Same applies to race, sexuality, disability, etc.

JS: In “Cora,” one of your characters says, “It sounds stupid, but I’m envious of people who’ve had some tragedy in their lives. If you’re homeless, or you’ve got no legs or whatever, success is easy. Your freedom is restricted, so the path is clearer.” I found that for many people this is true. Isn’t it true that all of us have a tragedy, but recognizing it makes us see the world in quite pessimistic terms?

CF: We are what we fight for. If you have never fought for anything, you are nothing. Jhon, I can’t imagine the trials and stress of your own experience, fleeing your home in Colombia to seek political asylum in the USA. I can understand how that might make you see the world in pessimistic terms. We all make a choice whether to submit, or fight. To accept, or resist. To conform, or become.

The characters in “Cora” are debating whether someone who has never had to fight for anything is actually disadvantaged because that choice has been denied to them. It’s a specious argument if you consider the depths of prejudice and injustice that pervade our society. Anyone who has never had to fight is extremely privileged, and to take that privilege for granted is an insult to those less fortunate.

JS: Thinking better now, another theme of the collection is freedom, success, and commitment too. Cora, Baggio, Remission, Go, and Second Place, among others, talked about that, don’t you think?

CF: Freedom is definitely something I think about a lot. I am thankful for many things in my life – my wife, my home, my family and friends, my health – but above all, my freedom. Because, despite the fact that so many of us take it for granted, freedom is fragile, and without it everything else could be taken away in an instant.

And yet we live in a society where we have overdosed on freedom. We have decades of knowledge and entertainment at our fingertips. We can travel the world. We can select our jobs, our partners, our lifestyles from a thousand different options. We choose a path, and we are constantly bombarded with reminders of all the paths we didn’t choose. Freedom of religion is used to protect damaging and anachronistic traditions, regardless of what the scriptures actually say. Freedom of speech has been weaponized. Can there be too much freedom?

This dilemma represents a rich seam that I suspect I’ll be exploring for a long time to come.

JS: While writing my questions to you, I got the sad news that Salman Rushdie was attacked during a presentation that he was giving here in New York. Of course, I want to hear your thoughts about it.

CF: Sad news indeed. My heart goes out to Salman Rushdie and those close to him. That kind of violence is deplorable, even more so the people and institutions that tacitly support it.

Censorship and suppression are often self-defeating, as demonstrated by the recent news that sales of The Satanic Verses have surged following the stabbing. The word is mightier than the sword.

JS: Finally, tell me about your upcoming projects. Is a memoir on its way, perhaps “The Man Who…?”

CF: Writing a memoir would require having a good memory, which I certainly don’t! I’m much more comfortable making stuff up.

I’ve just finished a short story, so I’m in the exciting position of being able to choose my next project. Want to work on something together, Jhon?

Meanwhile, to reward the readers that have got this far, I’d like to offer a giveaway. If you would like a free copy of The Man Who Married Himself by Charlie Fish, follow me on Twitter @fishcharlie and tweet me your favourite short story. The first 10 people to do so who also give me their postal address, will earn a free signed copy of the book.

JS: Thank you so much and I hope we can put our heads together for a future project.

Charlie Fish is a popular short story writer and screenwriter. His short stories have been published in several countries and inspired dozens of short film adaptations. Since 1996, he has edited Fiction on the Web, the longest-running short story site on the web. He was born in Mount Kisco, New York in 1980; and now lives in south London with his wife and daughters.