What the coup against the constitutional government of Hugo Chávez on 11 April 2002 made clear was that the insurgents, civilian, religious, military, Venezuelan and foreign, did not count on the reaction of an unarmed people who took to the streets, unarmed, to demand the return alive of the “commander”, to ensure the process of change and participatory democracy.

By Aram Aharonian

In recent months, Venezuela had become a privileged laboratory of geopolitics, where a series of destabilisation scenarios were practised which, if successful, could well be applied in other Latin American nations. The case of Venezuela was not atypical but symptomatic, where the constitutional order, democracy and the new rule of law were at stake, which no longer defended, with the 1999 Constitution, the economic interests of corporations and transnationals.

In mid-April 2002, although a civil war was avoided, many masks fell, both in the civilian, political, business, trade union, religious and military worlds. No institution was left unscathed; almost all were left with multiple fractures.

Every 11th has its 13th: the people responded to the coup of the 11th with the mobilisation of the 13th, despite the media blackout, with radios and television stations that played “llanera” music and avoided broadcasting what was happening. In the early hours of the morning of the 14th, Chávez finally arrived at the Miraflores Palace, without knowing exactly what the situation was: the people were still waiting for him in the warm Caracas night.

Days before, the new neoliberal guru from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology had stated in Caracas that it was necessary for the opposition to think that the country had lived through more than 20 years of bad economic policies and bad management, although he also delighted the businessmen present at his conference with pedantic phrases such as “Venezuela is a gas station south of Miami” and “what you see is the opposition like wild beasts fighting over the same piece of meat”.

Teodoro Petkoff, a former guerrilla fighter, founder of the Movement Towards Socialism and also Minister of Planning under the conservative Rafael Caldera, used to say that Venezuela was such a sui generis country that the opposition prayed for lower oil prices.

Two decades ago, they wanted to assassinate the dream

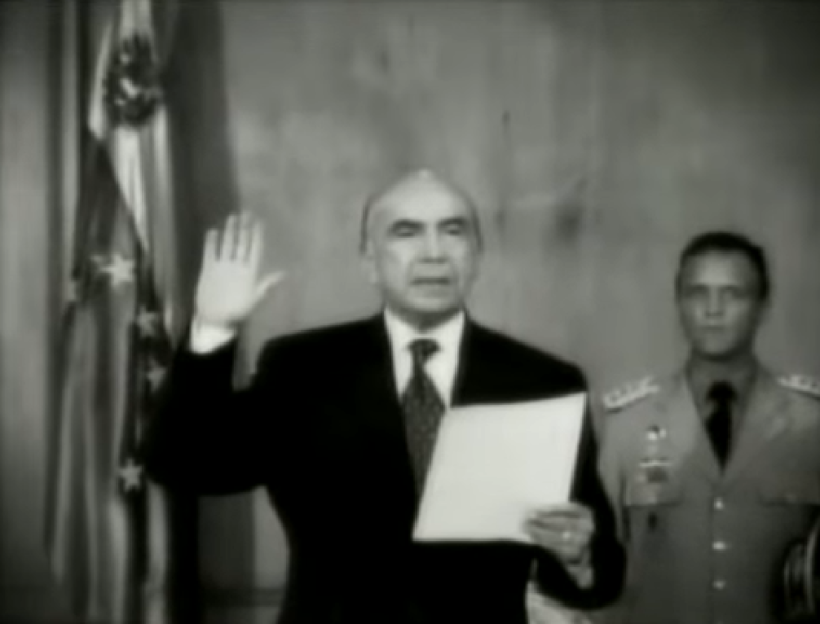

Twenty years ago, I reported in the Venezuelan monthly Question (Un golpe con olor a hamburguesa, jamón y petróleo) that a Spanish journalist said, after the foiled coup against the constitutional government of Hugo Chávez: “What a smell of hamburger, jabugo and oil!” Obviously, the man knew what he was talking about: the involvement of US, Spanish and Salvadoran officials in the coup led by business leader Pedro Carmona.

None of these claims seem far-fetched today, since the US and Spanish ambassadors themselves, Charles Shapiro (who formerly manned the Cuba desk at the State Department), and Manuel Viturro, met with de facto president Pedro Carmona, afterwards he dissolved the Assembly and the main institutions.

According to private investigations, one of the consequences of the coup was the denationalisation of oil: privatisation of Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA), to leave it in the hands of a US company linked to President George Bush and Spanish Repsol; selling PDVSA’s US subsidiary, Citgo, to Gustavo Cisneros and his partners from the same northern country; and the end of the Venezuelan state’s subsoil reserves.

To achieve this, it was necessary to ignore the 1999 Constitution and take advantage of the conflict in the state-owned company, where the top management played along with the directives sent from the north by its former president, Luis Giusti. And for this purpose, there was also the active participation in the coup and its financing of the businessman Isaac Pérez Recao, of whom Carmona was an employee in the Venoco oil company.

A high-ranking military source told Agence France Press what had already been published in the local press: that Pérez Recao was in charge of a small group of “right-wing extremists, who were heavily armed, including with grenade launchers, […] under the operational leadership of Rear Admiral Carlos Molina Tamayo”, one of the officers who had already publicly rebelled against Chávez in February 2002 and who was already in charge of Carmona’s military house.

This group “belonged to a security company owned by former Mossad agents” (Israeli security, terrorism and espionage services). This assertion was not surprising either: the “Rambo” who personally guarded Carmona was Marcelo Sarabia, linked to security agencies and companies – some of them Mossad franchises – who used to boast of staying overnight in the US embassy bunker.

The private US intelligence agency Stratfor denounced that the CIA “had knowledge of the [coup] plans, and may even have supported the extreme right-wing civilians and military officers who tried, unsuccessfully, to take over the interim government”, citing Opus Dei militants and officers linked to retired general Rubén Pérez Pérez – son-in-law of former president Rafael Caldera – as participants in the coup.

What has been confirmed is that the plane in which Chávez was to be removed from the island of La Orchila belonged to the Paraguayan-born banker Víctor Gil (TotalBank). The destination? According to personnel of the US-registered aircraft, the flight plan was to Puerto Rico, a US territory?

The intervention of the Americans was not only in the “advice” of high-ranking officials in Washington, such as Rogelio Pardo Maurer – in charge of special operations and low-intensity conflicts in Latin America at the Pentagon – Otto Reich and/or John Maisto, but Lieutenant Colonel James Rodger, attached to the military attaché’s office of the US embassy in Caracas, seconded the uprising with his presence, installed on the fifth floor of the Army Headquarters, from where he advised the revolted generals.

Reich, in charge of Latin American affairs at the State Department, claimed that he spoke “two or three times” during the coup with Gustavo Cisneros, the deep-sea fishing partner of former US President George Bush and the head of a business empire that stretches from the United States to Patagonia (DirectTV, Venevisión, Coca-Cola, Televisa).

Perhaps the case of two Salvadorans arrested after the 11 April incidents and who, according to local intelligence sources, were part of a death squad trained to carry out attacks in various countries (previously in Cuba and Panama, now in Venezuela) caught the attention of the public.

The plotters, including Carmona, met at Venevisión on the afternoon of the coup. “That government was assembled in the offices of Gustavo Cisneros,” said opposition deputy Pedro Pablo Alcántara of Acción Democrática.

The fallout from the foiled coup began in Washington and threatens to become the Bush administration’s first public foreign policy scandal. After Carmona’s plutocratic government dissolved the National Assembly and disregarded the Constitution, and after seeing the unease among the heads of state of the Rio Group meeting in Costa Rica, a large part of the generals and the civilian opposition to Chávez, talk began of a pluralist government junta that would respect the validity of Congress, governors and mayors.

The audiovisual team led by filmmakers Kim Bartley and Donnacha O’Briain, who had come to the Miraflores Palace to document the fall of Chavismo, ended up recording for posterity the shameful escape of the coup leaders. In their flight from the Miraflores Palace, the coup leaders left behind a sumptuous lunch and several documents in the president’s office. One of these was sent by Luis Herrera Marcano to what was undoubtedly the coup leaders’ liaison with the US government, Rear Admiral Molina Tamayo (communication 913, strangely on the letterhead of the Venezuelan Embassy and not the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela). The message began: “This morning I was contacted by telephone by Mr. Phillip Chicola of the State Department to ask me to urgently communicate to the Venezuelan government the following views of the US government”.

He pointed out that the transition needed to preserve constitutional forms. Chicola made it very clear that this was not an imposition, but an exhortation to make it easier for them to formally support the new authorities, and suggested that the new government address a communication to Washington as soon as possible, formally expressing a commitment to call elections within a reasonable period of time, elections in which OAS observers would be welcome. He also indicated that it was of great importance that a copy of the resignation signed by President Chávez be sent to them and expressed his hope that the current Permanent Representative of Venezuela to the OAS would be promptly replaced. “Finally, Mr. Chicola said that this same message would be transmitted by the US Ambassador to Venezuela”, Molina Tamayo’s communication stated.

Intrusion? Suggestion?

The script had already been learned by the representatives in the OAS Permanent Council. There, César Gaviria, the Colombian Secretary General, had suggested that since the Chávez government had been deposed, Ambassador Jorge Valero should not attend the meeting. El Salvador, Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Colombia were pushing for recognition of the de facto government, while Mexico, Argentina and Brazil, with the unanimous support of the Caribbean countries, insisted on the debut of the Democratic Charter. One of those quick to support Carmona’s government was Santiago Cantón, rapporteur of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, who on Saturday 13 sent a communication addressed to “His Excellency the Minister of Foreign Affairs, José Rodríguez Iturbe”.

On the Spanish side, neither Foreign Minister Josep Piqué nor embassy officials in Caracas could conceal the jubilation. Some Spanish businessmen, who got on better with Chávez than with the embassy, claimed that there was a pot of just over half a million dollars to co-finance the general strike and the coup, with money from large consortiums such as Repsol and banks.

In any case, Viturro brought together all high-ranking Spanish personnel to make it clear what strategy they will follow from now on: insist by all means on the need for a referendum or for Chávez to call new elections in the short term. Exactly the same strategy launched by Shapiro from the Valle Arriba bunker, southeast of Caracas, to English-speaking journalists accredited in the country.

20 years is nothing

“Who reads ten centuries of history and does not close his eyes when he sees the same things with a different date? The same men, the same wars, the same tyrants, the same chains, the same phonies, the same sects, and the same, the same poets! What a pity, that everything is always like that, always in the same way,” said the Spanish poet León Felipe in the middle of the last century.

There were the United States and Spain in full interference, programming from afar the coup against Chávez, accused of touching the untouchables, owners of the media and of almost everything, who with total freedom wanted to exterminate freedom. The media machine of “democracy” turned Chávez into a tyrant, a delusional autocrat, an enemy of democracy, against whom – they said – the citizens were rising up, and who was defended by “the mobs”, who gathered in “dens”. But the media coup only succeeded in promoting a virtual government, that of the “unmentionables”.

George Bush’s dream was to annex Venezuela to his country, as his predecessors had already done with Texas. Also, in the midst of the gold rush, California was acquired by the US in 1848 after the military defeat of Mexico. And in the midst of the oil crisis, Washington pulled out all the stops to appropriate the largest reserves of Negro gold.

Shapiro and Viturro are no more, but the attitude of Americans and Spaniards – like that of Western Europeans and Christians – has not changed much. During Nicolás Maduro’s government the US applied additional sanctions on the oil, gold, mining and banking industries. Economic sanctions have been extended and tightened since 2015, with the aim of creating a social crisis to justify a forced change of government.

Frustrated coups d’état, the invention of a parallel government monitored and financed by Washington to which companies and confiscated funds were transferred – including gold in the Bank of England – attempted invasions and assassinations, opposition violence financed by Washington and encouraged by Spain, induced inflation, attacks on the national currency and threats of military intervention, continue to this day. But Venezuela is resisting.

The ghostly voice of Carlos Gardel resounds in the Teatro Principal, in the middle of Plaza Bolivar in Caracas, where he performed on 26 April 1935 “20 años no es nada…” (20 years is nothing…).