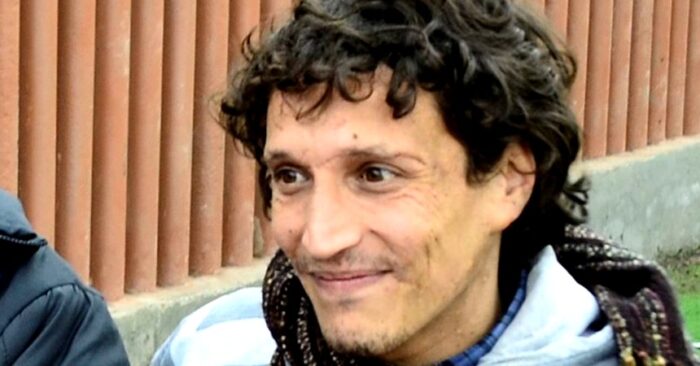

Two years afterwards, the death of the Argentinean journalist is still under suspicion. Without his body, which was cremated, the investigations have focused on photographs, videos and testimonies. The family, meanwhile, points to the responsibility, or at least the clumsiness, of some diplomats from the previous administration in La Paz, Bolivia.

By Noelia Carrazana

Editor’s note: This report was produced with the support of Unesco and the Global Defence Fund, as part of an international programme against impunity for crimes against journalists.

In the months leading up to the 2019 elections, the Plurinational State of Bolivia was shaken by fires in the Chiquitania, medical strikes and the mobilisation of the opposition, which had won only one election since 2005, following the rise to power of the Aymara Evo Morales.

On 20 October, election day, in the midst of a controversy with the opposition over the constitutionality of a third successive term, Evo Morales won 47.08 percent of the vote and was proclaimed the winner.

The opposition, which would be backed by the Secretary General of the OAS, the Uruguayan Luis Almagro, rejected the result and began a series of demonstrations that led to the burning of electoral tribunals and mayors’ offices, as well as attacks on supporters of President Morales, who fled to Argentina.

The events began to unfold on 22 October, two days afterwards, when opposition leader Luis Fernando Camacho, president of the Pro Santa Cruz Committee, called for an indefinite civic strike against the re-election of Evo Morales, which managed to take over the country’s main streets and attract the attention of the international media.

“We have to remove them from the agenda as Pablo Escobar did, but only to write down the names of those who betrayed the people,” Camacho declared on 31 October, referring to supporters and militants of the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS), Morales’ party.

“We have to remove the agenda as Pablo Escobar did, but only to write down the names of the people’s traitors,” Camacho declared on 31 October, referring to the supporters and militants of the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS), Morales’ party.

On 6 November, when Camacho entered La Paz to demand Morales’ resignation, journalist Sebastián Moro described a state of collapse. “Bolivia is still semi-paralysed, shaken by protests, blockades and incidents since ten days ago, when Evo Morales was projected to be re-elected in the first round”.

On the same date, journalist Christian Velasco Rojas, a member of the communication platform, La Resistencia Bolivia, denounced threats against him on Facebook. “What kind of democracy do they defend: the democracy of intolerance, of harassment, of vandalism? (…) This morning, in the name of Democracy, they painted my house with insults and threats, in the best style of Nazi Fascism where they marked the houses of Jews to afterwards burn them”.

I received messages on my mobile phone,” Velasco continued, “saying that President Morales had already fallen and that now it was our turn to die. These messages reached my whole family.

Meanwhile, in Cochabamba, members of the paramilitary Resistencia Cochala – JCR – kidnapped the mayor of Vinto, Patricia Arce, and burned down the town hall. In front of the cameras, they forced Arce to walk barefoot through the street on glass. They then urinated on her and dipped her in red paint, while shouting “murderer” at her. “I am in a free country (…). If they want to kill me, let them kill me. I will give my life for this process of change”, the mayor replied as they held her back.

Journalist Marcos Moscoso, who was Moro’s co-worker recalls that members of these groups “acted in collusion with the police.”

ATTACK ON PUBLIC MEDIA

As early as 22 October, the day on which members of Resistencia Cochala burned the equipment of the Kausachun Coca radio station in Cochabamba, the violence spread to all the public media. BTV-Bolivia TV, the radio stations of social organisations, Red Patria Nueva and the headquarters of the CSTUCB (Confederación Sindical Única de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia), where Prensa Rural was based, were attacked.

At that time, Sebastián Moro, in addition to being a correspondent for Página 12, was the editor of Prensa Rural, an organ of the Confederación Sindical de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia, one of the pillars of Evo Morales’ government. That day, the website of this press organ was hacked and its headquarters taken over.

On Saturday 9 November, the image of José Aramayo, CSUTCB media director, tied to a tree went viral. Paramilitary gangs who had arrived in La Paz with civic activist Luis Fernando Camacho were responsible for the attack on Aramayo, who was subsequently detained by the police, only to be released hours afterwards.

“A coup d’état is underway in Bolivia”, was the title of the last article that Sebastián Moro wrote for Página 12. “With the police in mutiny, the Armed Forces announced that they would not intervene in the streets and called for a ‘political solution’. The opposition calls for the resignation of Evo Morales. The agrarian unions take to the streets of El Alto to support the president,” he wrote.

On Sunday 10 November, Evo Morales announced in the morning that he would call for new national elections. The OAS, in parallel, demanded the annulment of the October presidential elections and the holding of new elections.

The UNITEL TV network and other mass channels began to broadcast the successive resignations of ministers and the president of Congress almost uninterruptedly. The FORCE and the police demanded the president’s resignation. Finally, at 5 p.m., Evo Morales announced his resignation afterwards after 13 years in power.

Jeanine Añez proclaims herself president of Bolivia in a session of the Assembly, without the quorum required by law. Roxana Lizárraga is appointed Minister of Communication in his cabinet, and in one of her first statements she takes aim at the press.

“What some Bolivian or foreign journalists who are causing sedition in our country are doing, they have to respond to Bolivian law (…) these communicators have already been identified”, warned the new minister.

In the midst of this situation, the Argentine embassy began to shelter journalists and cameramen from Argentina who had arrived to cover the crisis and the coup d’état.

Sebastián Moro was neither sought nor sheltered. On Sunday 10 November 2019, no one could reach him on his phone. Finally, he was found dying in his home in the La Paz neighbourhood of Sopocachi. His sisters Penélope and Melody, Sabrina, his niece, and his mother, Raquel Rocchietti began his ordeal that day.

PEACE IS A BATTLEFIELD

Argentine journalist Gloria Beretervide, who had returned home from Bolivia on 25 October, recounts her last conversations with Sebastián Moro. “On Saturday 9 November, Sebastián was interviewed by me for my regional column on the Fe de Radio de Bolivia radio programme and about the coming coup. That night I spoke to him again at 10 p.m. because Sebastián was due to appear the following day at 9 a.m. Bolivian time on a well-known radio programme with international correspondents around the world”.

His sister Penélope Moro said that she spoke to Sebastián for the last time on Saturday 9 November at 11pm. He told her that due to the blockades he had given up presenting the Abya Yala TV programme. However, she told him that she was going for a walk to get some air, as she often did. Penelope and the rest of the family in Mendoza, worried about the situation Sebastian described, spent a sleepless night.

On the morning of Sunday 10, unable to reach Sebastián, the family began to call acquaintances and friends who could visit the journalist’s house. They were all afraid to do so because of the threats they had received. Finally, a witness, now protected by the Bolivian justice system, accepted the call and found Sebastián lying in bed, unconscious and apparently in a state of semi-consciousness.

“I found him in bed, he even recognised me. I’m fine, hello Willy’, he said. ‘You’re in bad shape,’ I replied. Sebastian insisted he was fine, but I could tell he wasn’t because everything smelled strongly of urine. When we arrived at the Rengel clinic, the nurses called me to change him and there I saw the bruises on his arm and body. Afterwards, the Argentinean consulate came and then I left him in their care and did not go to see him again”, explained the witness.

The family decided to travel immediately while they communicated with the Consulate and the Argentinean Embassy in La Paz. Penélope managed to travel the same day that Senator Jeanine Añez assumed the presidency.

In La Paz, the Argentine Consulate informs the family that it is unable to provide financial support. The Embassy, allegedly due to street violence, refuses to provide help to leave El Alto airport for La Paz, where Sebastián was hospitalised.

Penélope Moro explains that the lack of collaboration from the Argentinean diplomatic authorities occurred from the beginning. This situation was denounced by the family in the press and is also recorded in the case of Sebastián Moro’s death.

Penélope, with the help of friends, managed to get out of the air terminal and avoid the clashes. “There was no way out of El Alto because of the blockades with fire; in that context, the journalist’s credentials were useless. We went back and forth several times, there were places where we had to get down to remove the very heavy stones that were placed in the streets to block the roadblocks. We camouflaged ourselves with white flags like the ones used by the ‘pititas’ (coup supporters) and it only took us six hours to get to the Rengel clinic,” she recalls.

Once at the clinic, Penélope managed to see her brother afterwards. There, she was given a medical report stating that he had had several cardiovascular accidents and even informed that her brother had been admitted in an alcoholic state, as is even stated in some of the testimonies of the hospital staff in the case that is being heard in Bolivia. That day Raquel Rocchietti and Melody Moro, Sebastian’s mother and sister, arrived in Bolivia.

DISTANCE FROM THE EMBASSY

“On 14 November 2019, the Argentinean ambassador Normando Álvarez García gave a press conference in which he stated that the Argentinean journalists were under the protection of the embassy, but he forgot that an Argentinean journalist was dying in the clinic,” says Raquel Rochietti, Sebastián’s mother. Penélope, for her part, says that every time she entered the Rengel clinic in the Sopocachi neighbourhood, she was searched by the Pititas and that at no time did she feel protected.

On the day of those statements, the Argentine journalists did indeed manage to leave Bolivia, as did many other correspondents.

But the violence did not let up, and on Friday of that week the massacre took place in Sacaba, Cochabamba, and four days afterwards the Senkata massacre in the city of El Alto, resulting in more than thirty people dead and hundreds wounded, according to the latest report of the group of independent experts (GIEI) of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR – OAS).

The latest report of the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI), which was investigating the events under the management of Añez for more than six months, concluded on 17 August 2021 that “during that time, insults to journalism were commonplace and, as occurred in other cities and events included in this report, female journalists received insults with a marked sexist tone that added to the aggravations directed at all press agents.

“Many professionals were expelled from the places where they were reporting or prevented from entering public spaces that had been blocked (…) not only were their work hindered, but their equipment was confiscated or destroyed, their recordings were erased or their telephones confiscated”.

“A particularly serious case was the death, in circumstances that have not yet been clarified, of the Argentinean journalist Sebastián Moro”, the document remarked. “Polytraumatisms were identified all over his body”, it concluded.

Following the GIEI report, Bolivian President Luis Arce mentioned Sebastián Moro for the first time as one of the victims of the coup d’état.

Likewise, in July 2021, his case was picked up by some mass media, after the new Bolivian government denounced the shipment of arms from Buenos Aires to La Paz, during the presidential administration of Mauricio Macri, in the hours after the coup d’état.

A report by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), led by former Chilean president Michelle Bachelet, warned that “public statements by authorities claiming that some journalists had committed the crime of sedition” were “worrying”.

“Such statements could encourage violence against journalists and media workers, generate self-censorship and inhibit independent coverage,” the OHCHR said.

BACK TO THE ASHES

Sebastian’s family remembers those days as extremely precarious. “The clinic had nothing; they gave Penelope prescriptions for medication that any primary emergency health centre has. They asked for hospital supplies that my sister could not find in the pharmacy. We ourselves carried a large amount of medication and supplies: needles, probes, tapes that were asked for all the time. There is an investigation into this because it is a private clinic that charged us thousands of pesos and had everything outsourced. They couldn’t do any tests on Sebastian,” explains Melody Moro.

There was a lot of manipulation at the clinic,” she continues. One day they had us prepare to disconnect my brother and afterwards they told us that he was in no condition to be disconnected. We are talking about doctors, cardiologists, specialists. We were not allowed to touch him or see his back because we had already noticed something strange. We had seen bruises on my brother’s body; the clinic never gave us back his clothes,” says his sister Melody.

Normando Álvarez, who was Argentina’s ambassador to Bolivia during the government of Mauricio Macri, is accused by Moro’s family of indifference and neglect. When we found out that the embassy was involved in the arms shipment, I felt that my mother, my sister and I were in the hands of a criminal because he not only denied us the medical plane,” says Sebastián’s sister, Penélope.

She also explains that the ambassador “took the prescriptions with the medicines that my brother needed and never returned them to me or brought the medication”. The only thing the embassy offered us was a discount to stay in a hostel,” recalls Penélope Moro.

That week, 11 November, there were no banks due to mass protests throughout Bolivia. This made it impossible to change Argentinean money into Bolivian pesos to buy the medication her brother needed. The clinic “made us pay per day for the oxygen and buy all the supplies on the spot, which we saw was not the case for all the patients”, says journalist Penélope Moro, who is also a journalist.

Sebastián died at midnight on Saturday 16 November. “I feel that that hour marked a death to begin to be reborn every day,” says his mother.

Raquel also recalls that “the ambassador (Normando Álvarez García) appeared with the prescriptions, but without having bought the medicines, when they were already taking Sebastián’s body away”.

“Melisa Campitelli, the Argentinean consul in La Paz – the mother continues – accompanied us more than the ambassador, and told us that in order to return more quickly it would be better to cremate Sebastián’s body, and the Consul hurried to do all the paperwork. In the situation of having seen marks on Sebastian’s body, we were told to file a police report because the medical report continued to say stroke and polytraumatisms. So, there is negligence on the part of the Consul and the clinic. The Consul, the lawyer Melisa Laura Campitelli Mayor, in her dual role as lawyer and consular authority, could not have been unaware that when a body is cremated, the most important evidence is lost when it comes to ascertaining the cause of death”.

For the family, it is also striking that the ambassador, knowing that Sebastián was in the clinic, had not created the necessary mechanisms to be able to transfer him on the plane, together with the rest of the Argentinean journalists.

Therefore, Sebastian’s mother says that “there are people responsible for all these situations. “On 14 November, when the Hercules plane arrived with the war material (from Argentina) to repress the Bolivian people, Normando Álvarez sent the Argentinian journalists from the mainstream media to protect them in that Hercules in the early hours of the morning of the 15th. He had told us that it was not possible for a medical plane to arrive because of the context we were living in. When we later found out about the case of the Argentinean arms in Bolivia, that was also a blow to us.

On 29 November, at the Argentine embassy in La Paz, Ambassador Álvarez García held a reception for the coup perpetrators, in a ceremony attended by Áñez’s Minister of Defence, Fernando López, who is currently a fugitive from justice in cases related to the 2019 coup d’état.

The Argentinian digital newspaper El Destape Web, in an investigation including a photograph, reports that US, Brazilian and Ecuadorian military personnel were also present.

WOMEN FIGHTING FOR MEMORY, TRUTH AND JUSTICE

For us, death is the absence of someone we will never see again, and when it is an unnatural death, we have the need and the urgency to take the path of justice”, says Raquel, Sebastián’s mother, “When we came back from Bolivia, when we were in the country, we had to go back to our country, we had to go back to our country to find justice”, says Raquel, Sebastián’s mother.

“When we returned from Bolivia, despite the pain, the three of us sat down, and with pen and paper, we started to think about how we were going to denounce. Nobody has shut us up since we got back, we gave our names and surnames and we don’t know where the legal process will take us. We saw him (Sebastián) beaten”, she complains.

In Argentina, there are two open cases in which an investigation is being requested for clarification of the journalist’s death, one in Córdoba, in which the Moro family is a plaintiff, for crimes against humanity.

This case against some officials of Jeanine Añez’s government was brought before the Argentine Federal Court. The second case was opened in Mendoza and is under the legal representation of lawyer Viviana Beigel. Both lawsuits were filed invoking the concept of universal jurisdiction.

Also, in Bolivia there is a complaint being investigated by the prosecutor Dubravka Jordan Velázquez. “The case is classified as ‘homicide’, but no one has been arrested, no evidence has been produced and the facts have not been reconstructed; there is little seriousness in the investigation,” Beigel criticised before the last testimonies of key witnesses and the verification of the scene of the crime, which took place on the same day as the anniversary of Moro’s death, 16 November 2021 in La Paz.

“There are very serious suspicions that lead us to suppose that (Sebastián) could have been beaten to death as part of an attack on the civilian population, within the framework of a generalised attack on the population. We are awaiting the results of the Bolivian justice system”, says the lawyer from Mendoza.

For her part, the new Bolivian lawyer in the Moro case, Mary Carrasco, maintains that the judicial scenario is complicated, due to the fact that the body was incinerated, but clarifies that there are many testimonies and photos that can be analysed by experts, in order to finally arrive at the truth.

Carrasco explains: “We wanted to reconstruct his last hours: there were acts of torture, his arm had traces of having been wrapped with barbed wire, his face was beaten, his wrist was swollen, his legs in the same way, but something that was lethal and forceful was the blow to the lung that displaced him. So, this was not evident to the eyes of those who helped him, but the clinic reports that this was the most serious event”.

“The Public Prosecutor’s Office has asked for materials from the clinic, they have asked for testimonies from the doctors who saw Moro. Strangely enough, they are all on scholarships, doing courses abroad, but we have obtained statements from the nurses. It is a complex investigation because of the time involved, but we have to establish how and why Sebastián was killed; Bolivian procedural law has many tools for this: documentary evidence, testimonial evidence, photographs, filming, but essentially the expert evidence will help us. We have a medical record, the x-rays of Sebastián’s organs and the first erratic diagnosis in which they indicate that he inflicted the blows on himself because he was in an alcoholic or drugged state, without carrying out the corresponding tests. This thesis has collapsed, not only because of what we are experiencing today, but also because of all the testimonies that are being taken forward”.

The criminal lawyer, like the family, denounces the fact that many doctors avoided reporting these assaults. And not only that, according to her. “There are victims – from the Añez government – who say that when they entered the clinics, the doctors told the police, not to make an enquiry, but to intimidate them.

“The medical records are full of errors, controversies, Sebastian’s evolution that have nothing to do with what we saw as witnesses, and not having the body is a serious offence, the fault of the embassy and the clinic, as we were unaware of Bolivian law. When a health centre receives a patient in my brother’s condition, it is obliged to report the fact, we did not even have the advice of the consular authorities and the clinic did not report the fact; surely the body would have had a corresponding autopsy and the only option given to us by the embassy was cremation because it was dangerous for a medical plane to land in La Paz”, recalls Penélope.

Sebastián’s sister concludes by explaining that “the examination that took place in November last year was very important; it is the first one in two years with the Prosecutor’s Office and the investigation team. My mother and my sister were present to testify in the case. The most novel thing about this verification of facts, as they call it over there, is that the person who helped my brother and took him to the clinic came and gave her testimony. There, with the prosecutor, the investigators, and our lawyer Mary Carrasco, we entered Sebastian’s house.

CAMPAIGNING FOR JUSTICE FOR SEBASTIAN

In Aymara culture, the Ajayu is the soul that forms part of a person’s body. According to this belief, when a person suffers an accident or an act of violence, the ajayu leaves the physical body and only returns when the body is in harmony. In Sebastián’s case, there is no body to return to, but Sebastián’s friends invited his family to a similar ritual.

“Some of Sebastián’s colleagues took us to do a quitapena (farewell ceremony) at the Montículo, a place he liked very much. We bought salteñas (empanadas) and they made us put a photo in the middle, along with a blanket, some coca leaves and tobacco. We formed a circle and everyone began to talk about how they had met him, the music he liked (…); they thanked my mother a lot because she had brought him to life, they thanked her because she had taught us to tell stories, because she had passed on authors to us. It was very strong,” says Melody.

Raquel Rocchietti in her statement to the Citizenship and Human Rights Commission of the Mercosur Parliament (PARLASUR) said that Sebastián’s death “was a sobering message for the free press. He became the first victim of the dictatorship that was installed in Bolivia. There was intelligence about his activities. To deny it, to silence it, to hide evidence, constitutes a crime against humanity”.

“In Sebastián’s case, the responsibility falls on the police, because at that time they were rioting, but the de facto government of Añez was not yet in power, nor was the military, and to date there is no one in prison or charged for my brother’s case, which is why we are asking that these cases begin to be tried as crimes against humanity, so far there are only those charged for crimes of corruption and economic crimes,” says his sister Penélope.

In recent months, the Bolivian justice system has begun to issue sentences against members of the Cochala Youth Resistance, including Roger Revuelta Villaroel, sentenced to twelve years in prison for the crime of attempted murder and grievous bodily harm against journalist Adair Pinto.

The incident occurred in 2020 when Revuelta entered a bar and, together with a group of the Cochala Youth Resistance (RJC), insulted the journalist who had publicly denounced Jeanine Añez for the coup d’état on a radio station. Revuelta threatened to rape his younger sister of whom he had a photo. After 20 minutes, when Pinto was leaving the shop and trying to get into a taxi, he was intercepted by Revuelta who stabbed him in the heart, thigh and abdomen.

In this context, the current Attorney General of the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Wilfredo Chávez, told Argentinean journalist Gloria Beretervide, after the GIEI report was released, that the case of Sebastián Moro “has to be investigated”.

“Everything points to the fact that it was a murder, direct and with execution”, he stressed.

The case of Sebastián Moro will remain open for his family, Latin American society and human rights organisations forever, like many other murders, violations and violations of human rights by civic, military, police and ecclesiastical dictatorships in countries impoverished by a few who hold economic power and oppress the people by abusing the figure of political parties in the name of “democracy”, masking their own petty interests.