by Lina Merino and Agustina Medina

Every 11 February we remember the “International Day of Women and Girls in Science” established by the United Nations in December 2015. The date represents an opportunity to rethink the current situation of women, girls and dissidents in the scientific and technological field, and also to think about the importance of making visible the obstacles that prevent them from accessing and developing in this sector, promoting their full and equal effective participation.

The scientific and technological system is an environment that, like others, does not escape the reproduction of the capitalist and patriarchal system, where even with a growing feminist movement, we have a long way to go in favour of equality.

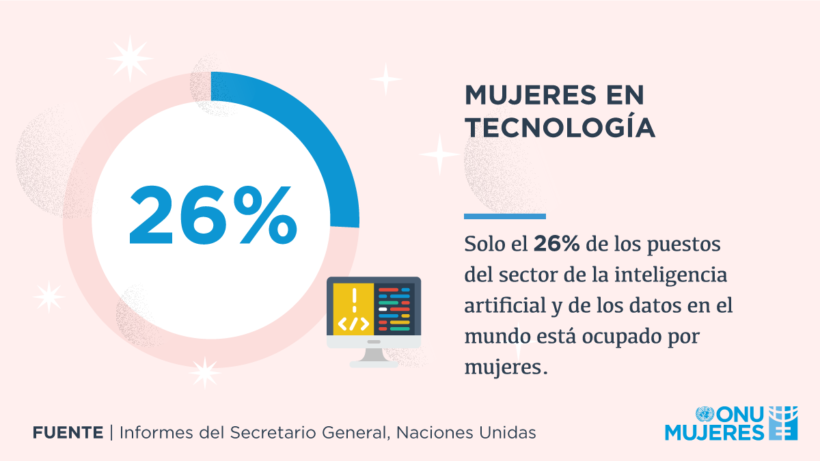

We are interested in analysing the role of women in a key sector for the current state of development of the productive forces, in the sectors with the greatest investment in knowledge, such as STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) careers. When we talk about “role” we are not only referring to the type of position held, but also to the possibility or not of actually occupying more or less hierarchical, decision-making and managerial positions, or other more secondary ones.

It is also central to analyse the level of access to political participation, understood in its full dimension, i.e., the degree of activism and organisation in which we are allowed to develop.

Recently, the Centre for the Implementation of Public Policies for Equity and Growth (CIPPEC) published a report on women’s participation in the field of science, research and technology in Brazil, Mexico and Argentina, which highlights that, in the very booming sector of the current and future economy, the situation is particularly unequal in Latin America. In Argentina, less than 25% of S&T employment is occupied by women.

This is due to multiple situations, and redressing them requires a comprehensive approach in multiple dimensions.

According to a study based on the Permanent Household Survey, the gap between men and women decreases as we move up the educational level. On the other hand, in highly educated institutions, such as universities and scientific institutions, women’s participation in the labour market is lower.

The way in which the unequal distribution of educational attainment limits our degree of labour participation translates into the need for more women to have access to universities in order to shorten the labour gap, but also the need for representation in hierarchical positions, a slogan that has been heard many times before but is still merely an exclamation point. It seems that the ceiling is made of bulletproof glass.

While some things seem to be changing too slowly for the times, life has taken astronomical leaps thanks to the technological revolution.

We are going through a stage of digitalisation of life, in which the degree of concentration of wealth is deepening, mainly in the technological giants, the so-called “GAFAMs” (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft), merged with the great transnationalised financial capital.

Artificial intelligence, robotisation-automation, big data, 5G technology, 3D printers, are areas of knowledge that occupy a preponderant place, being necessary and transversal for everyday life, they are now more than ever part of our way of relating, producing and consuming.

But this technological leap has been accompanied by a concentrated appropriation of its benefits. It is precisely those sectors that have appropriated the most knowledge that have managed to impose their plan and accumulate the socially produced wealth. These are times when not only science and technology are advancing, but also inequality is growing with enormous and worrying speed.

In this context, accelerated by two years of pandemic, social inequalities in general and gender inequalities in particular have deepened. According to a survey of 295 economists in 79 countries, 87% believe that income inequality will increase because of the coronavirus crisis, while 67% believe it is likely or very likely that gender inequality will increase (OXFAM, 2021). Thus, globally, women are over-represented in the economic sectors most affected by the pandemic (ILO, 2020).

The hinge time we are living through presents us with the opportunity to think about the role of science and technology, as well as the necessary insertion of women and diversity in the knowledge-intensive production system. Today’s world is developing in chaos and the institutions that once contained society have now become backward structures incapable of dealing with the concentrated economic power that is based in a complex global network.

In a context of increasing privatisation of resources and knowledge, is it possible to think about innovation with social justice? If we want to move towards scientific development based on equity and sustainability, we will have to break with structures and interests. To achieve this, we believe that it is time to deepen the production of knowledge for sovereign development. We need to leave behind agendas imposed with a “northern” perspective and focus on internal problems.

We know that historically, and increasingly so, science and technology have been able to alter the reality in which we live, making it a tool for building a society without inequalities. The role of scientists will be to question the world in which we live in order to transform it and be part of the construction of the world we want.

Feminism is a heterogeneous and transversal movement, capable of driving and leading transformation processes, questioning imposed patriarchal structures. Its power can generate the necessary conditions for girls, boys, women and today’s diversities to be the scientists of a new tomorrow that includes us all. We must be able to think of new relationships that allow us to advance in the struggle for equality and social justice, and to question the bases of all injustices, as a way to build a better reality for all.

*Merino has a PhD in Biological Sciences (UNLP), a degree in Biotechnology and Molecular Biology (UNLP), a Diploma in Gender and Institutional Management (UNDEF), and teaches at UNAHUR. Medina has a degree in Molecular Biology (UNSL) and is a PhD candidate at the University of Buenos Aires with a mention in Physiology, Faculty of Pharmacy and Biochemistry, (UBA). Both analysts at the Latin American Centre for Strategic Analysis (CLAE).