Brian Nichols, the State Department’s top official in the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs, visited Honduras the week before the presidential elections. The objective was to “promote the peaceful and transparent conduct of free and fair national elections”. Nichols did not meet with the de facto president, Juan Orlando Hernández.

By Patricio Zamorano / From Washington DC*.

The gesture was clear and clarifying on two levels.

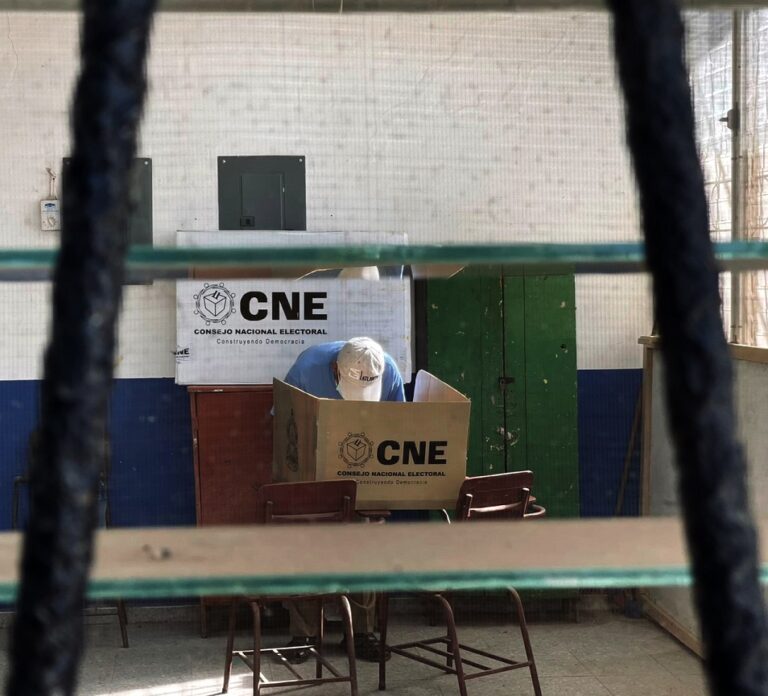

First, it showed that the US government had already accepted the irrefutable reality that the centre-left coalition led by Xiomara Castro would be supported at the polls by the Honduran people (at press time, it was leading with 53.6% [1]), with 5.1 million Hondurans also called to elect 3 vice presidents, 298 municipal mayors, 128 deputies to the local Congress and 20 to the Central American Parliament.

Alina Duarte/COHA

But secondly, the gesture of the American Nichols not to meet with the de facto president made it clear once again that the fate of Honduras remains under the irrepressible domination of the United States, which maintains in Palmerola the largest military base in Latin America [2], and which has supported the narco-government of Juan Orlando Hernández for 8 long years. With a clear electoral fraud in between.

Sanctions against Honduras that never came

Supporting a third electoral fraud in Honduras would have been a political indecency that not even the northern power could sponsor this time, as it did in 2017[3]. In 2014, there were serious accusations of fraud that went unheeded by the international community. And in 2017 the Organisation of American States (OAS) itself certified a new fraud, publicly stating that it could not declare Hernández the winner, and calling for new elections [4]. The pressure ‘for continental democracy’ only went so far, as the OAS never suspended Honduras from the Permanent Council in Washington DC, maintained the diplomatic representation office in Tegucigalpa, and basically treated the Hernández de facto government as absolutely normal. There have never been any US sanctions against the Hernández narco-government. Isn’t this an outrageous double standard?

In the meantime, the US courts of justice did not follow the script of the Trump and Biden administration. An investigation in New York for drug trafficking against the brother of the de facto president, Tony Hernández [5], forever recorded in the judicial records the name of Juan Orlando Hernández himself with protection for drug traffickers, bribery and organised crime activities [6].

Alina Duarte/COHA

US military presence in a narco-state

The levels of violence, crime and corruption in Honduras have soared to historic levels, creating the immigration wave of thousands of desperate families knocking on the door of the southern border (Honduras is the third country in the Americas in terms of homicides per 100,000 inhabitants [7]). This under the watchful eye of US military units in Honduras, troops and intelligence personnel who, for some reason, have zero and almost comical effectiveness against the organised crime that uses Honduras as a bridge for transporting illegal drugs from Colombia, another US ally.

How does one explain that Juan Orlando Hernández’s own family and the dozens of drug cartels in the country can operate so comfortably, under sophisticated US technological surveillance present on Honduran territory itself? The United States, as the world’s largest consumer of illegal drugs, also feeds the crime network that shakes Honduras and all of Central America. The crisis also directly affects Mexico, which faces great immigration pressure at its own borders. The policies of Xiomara Castro’s new government will have an influence in this area.

Political and economic feudalism that kills thousands

The history of Honduras is a history of political feudalism that still keeps the country trapped between political forces that do not end up re-founding the country under a new social contract that is urgently needed. Every day that the country remains in chaos, dozens of Hondurans lose their lives, are kidnapped, injured, or forced to flee the country.

The US and the OAS are directly responsible for the debacle of the last 12 years. The 2009 coup d’état that ousted President Manuel Zelaya proved the fragility of Honduras’ political institutional system. One of the coup plotters’ justifications was the discussion under Zelaya’s government of reforming the constitution to democratise it, including opening up the possibility of re-election of presidents. A few years later, the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court, in favour of Hernández, did exactly that, authorising de facto, without constitutional reform, Juan Orlando Hernández to re-elect himself, despite the fact that article 239 of the Constitution prohibited it [8]. This time there was no coup and no US claims.

In 2021, the US and the OAS seem to wash their hands of this scandalous past, removing from the equation an undesirable de facto president who is no longer capable of keeping Honduras aligned with the strategic geopolitics of the North, with his candidate Nasry Asfura of the National Party, collecting only 33.8% of the vote.

Alina Duarte/COHA

A new phase of uncertainty

The isolation to which the US has subjected Juan Orlando Hernández in recent months has only reflected the de facto president’s great unpopularity.

The big question is how the US will behave towards the new president, Xiomara Castro, wife of ousted president Manuel Zelaya, a former latifundista who made a huge ideological shift towards continental Bolivarianism and became an ally of Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela in the late president’s strong years.

The alliance that backed Xiomara Castro brings together centre-left forces that will have a tough job in creating a government and countering the penetration of drug trafficking and organised crime. The presidential alliance includes the Liberty and Refoundation Party, LIBRE (whose coordinator is former president Zelaya) and the “Salvador de Honduras” party, chaired by former presidential candidate and victim of fraud in 2017, Salvador Nasralla. Also, part of the coalition are the Partido Innovación y Unidad-Social Demócrata (PINU-SD) and the Alianza Liberal Opositora, among others.

Political and social re-founding of the country: first urgency

But the most important challenge is to move forward with the process that the 2009 coup d’état, left unfinished. The Honduran constitution is profoundly anti-democratic. It still contains ‘stone articles’, as they are called in Honduras, institutional foundations that cannot be reformed (except in implausible acts such as the Supreme Court’s approval of Hernández’s re-election).

The most important challenge for Honduras is a new social contract between the state and citizens that “democratises access to democracy”. A feudal and retrograde elite that continues to rule the country must open up real spaces of representation for the vast 50% of the country’s languishing poor [9]. Social, gender, peasant, indigenous, trade union and cultural groups must have access to representative positions in Congress, in political parties, in the ministerial cabinet of presidencies.

The international community can play a vital role in supporting the democratisation that Honduran voters are clearly demanding, to give Xiomara Castro’s government the space, support and financial assistance to make the necessary changes without facing the economic and political attacks that some Latin American governments suffer from the US, and also to put pressure on the entrenched Honduran elite in power. The Honduran people have suffered enough, as the humanitarian tragedy on the southern US border has shown. It is an ethical obligation for all actors who claim to believe in democracy to respect the wishes of the majority of Hondurans to take the country back from drug traffickers and organised crime and build their own form of democracy, free from external interventionism.

*Patricio Zamorano is an international analyst and Director of the Council on Hemispheric Affairs (COHA).