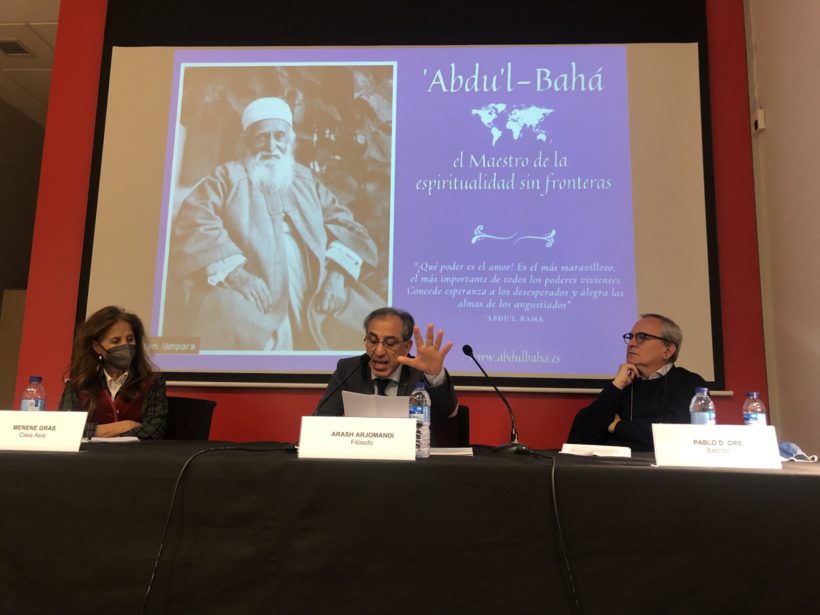

We spoke with Arash Arjomandi and Pablo d’Ors, on the occasion of the dialogue they held in Madrid (Casa Asia), entitled “‘Abdu’l Bahá, the master of spirituality without borders”.

While Arjomandi introduced us more to the figure of ‘Abdu’l Bahá, d’Ors took us to the spaces of silence, where we can meet with ourselves, with others and with “the mystery of Light and Love, which is what we call God”.

This meeting is part of the events that the Bahá’í Community is holding around the world during these days, in commemoration of the centenary of the death of the son of the prophet of the Bahá’í Faith, Bahá’u’lláh, who spread and developed the principles and proposals of his father throughout Europe and North America.

Pressenza: For those who do not know his work, what is the contribution that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá makes to the Bahá’í Community and to the world?

Arash Arjomandi: There is a confluence of several reasons. From the point of view of a Western citizen, according to the media of the time – specifically, the New York Daily – he was the first Eastern figure to visit the United States. He was in Europe and North America, spreading a series of principles that, for the time, were very avant-garde. They were all spiritually based but aimed at improving society, not just the individual and his or her well-being.

He, spoke of gender equality. We are talking about the first decade of the 20th century. But not in a tangential way, he put it at the centre, and said that peace is not possible – remember that we are at the gates of the First Great War – if women do not enter the scene of leadership and the administration of affairs, something that today the economy has demonstrated.

On the other hand, he predicted the Great War two or three years earlier in the US media and people did not believe it, but also what could be done to avoid it. Among other things, it is documented that his work and ideas influenced President Woodrow Wilson, through his eldest daughter, to create the League of Nations. There he was talking about an international governance structure that could arbitrate in conflicts.

He, spoke of the need for religions to dialogue with each other. He said: “the most religious thing is to have no religion, if it is to confront”.

Another fundamental principle he defended was that religion and believers had to respect objective science much more, because it was the only way for the advancement of civilisation to have both dimensions: the material and the spiritual.

That which is a century and some time ago, now has had a very big footprint, because the Bahá’í Community (7 million followers around the world) today is working in the world for all these initiatives.

Pressenza: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spread his father’s doctrine in Europe and North America, as you pointed out, what is the Bahá’í Community doing today to transfer these teachings?

Arash Arjomandi: It works on three or four lines at the grassroots level, in the neighbourhoods; it also has its structures at the UN to influence, to promote these ideas of international peace. Abdul Baha talks about a World Federation of Nations. But at the neighbourhood level, at the grassroots, he works on spiritual education for children, but in a very cross-border way, not necessarily from a confessional adoption. So, it works on education in values, values that are not taught in schools, because schools teach secular values, which is fundamental, but they are insufficient.

We also do things similar to what Pablo does, which he does excellently, which is to try to promote some introspective practices, through prayer, meditation, contemplation, because that really helps the wellbeing of the person. We also have programmes with young people, to empower them towards these universal values.

Pressenza: You have spoken of bringing spirituality to young people, to children, to the community, without it being confessional, are we talking about a universal spirituality?

Arash Arjomandi: I don’t necessarily mean non-denominational. I mean that when the Bahai Community or another community does it, it is not necessarily to enhance the Bahai name, the objective is something else. If, on that path, there is someone who expresses an interest in joining the Bahai Community, or other spiritual paths, it is facilitated. I believe that one of the mistakes of our time is to want to create a spirituality at any cost, emptied of its religious substratum.

“For there to be spirituality, it has to produce a fruit of harmony and compassion.

Pressenza: By religious substratum do you mean associated with certain figures?

Pablo d’Ors: I usually say that religion is the cup and spirituality is the wine. It seems to me a very clear image. Or if you prefer, form and substance. Religion is cultural, linguistic, liturgical, ritualistic forms… for what we call spirituality, which is nothing more than the connection with the deep self, with the mystery of the Self, whatever we want to call it, or God in religious language.

Spirituality is gaining more and more prestige, curiously, thanks to the discrediting of religion. In other words, many people today define themselves as spiritual, but not religious. When we enter into this debate, I always say: ‘tell me ten names of non-religious spiritual people’, and practically nobody is able to give me a single name. In our culture, religion has been very much associated with spirituality. Maybe they name thinkers, or artists… Of course, thought and art can be spiritual, but not necessarily.

For there to be spirituality, in addition to other things, it has to produce a fruit of harmony and compassion. That is to say, harmony towards oneself and compassion towards others. If your religious, artistic, intellectual or altruistic practice does not produce harmony and does not serve to generate humanity and fraternity, I would not call it spirituality.

Silence as a path and spiritual encounter…

Pressenza: What spiritual experience could unite all Humanity, all people, and how to access it, what steps to take…?

Pablo d’Ors: It is clear to me. I think we have to move from inter-religious dialogue to inter-religious silence. Nothing can unite us as much as being together in silence, because I believe that the word can generate, in the best of cases, intellectual or sentimental affinity. Intellectual: I agree; sentimental: I like you. This is at best, although it usually generates dissension, even confrontation. Whereas silence, under a series of assumptions – it is not a question of being quiet, just being quiet – silence, ritualised silence, as an interior search, generates spiritual communion.

Pressenza: Where does the silence you speak of lead?

Pablo d’Ors: To this communion we are talking about, to realising that if I am in my depths and you are in your depths, that is where the true encounter can be made possible.

The problem is that we are not at the bottom. As we are in the forms, that is where there is conflict. But if we really managed to be in our own depths, there would be no wars in this world. There would be universal peace. For me, that is universal spirituality.

Arash Arjomandi: I have experienced this silence. All people who have gone trekking, they experience it. When you go hiking with a group, normally you don’t know most of the people because they are open groups, a very curious phenomenon happens: after five or ten minutes of walking, in the forest, in the mountains, the feeling you get is that you know these people from long before, from always. And often they don’t speak, and I think that this is partly the effect of silence, a silence that makes sense, that is not empty, and that is where this effect is produced, which is experienced.

Pablo D’Ors: This is very nice, I totally agree. In fact, walking or strolling is a spiritual exercise. I think that there, more than the silence, which also influences it, there are two things that generate a kind of fraternity among all the walkers. In fact, you go along a path and say ‘good afternoon’, and you go through the city and you don’t say good afternoon to whoever you pass, and I think that this is due, firstly, to nature. We are good in nature because we are nature. That context brings you back to the fact that there is no difference between one and the other and it evokes you. That is to say that part of our undoing is that we have lost contact with nature. And the second thing is that, when you go hiking, you are on a path. And the path is possibly the most perfect, the most successful metaphor for what human life is. So, when you are in such a symbolic reality as a path, you are united with everything there is, with the sun, with other people… and because of that, you feel united.

I believe that nature, the path, the walk, for example, the inter-religious march, this unites us more than any congress. Well, Gandhi already knew that, for sure.

What do you expect to find at the end of the road?

On this path you are talking about, Pablo, and the one you have taken us on, Arash, what are you looking for, what do you hope to find at the end of this path of life, of spirituality?

Pablo d’Ors: Me, to meet God, I am a believing man. That is to say, with the mystery of Light and Love, which is what we call God.

Arash Arjomandi: That, said from another angle, is the search for happiness, inner and outer well-being. You seek to be well, but differentiating it from short term pleasure because that too has been proven – from all sciences – that it does not last and requires an escalating effect, that you never finish. On the other hand, when we talk about happiness, inner well-being, life satisfaction, it is something that is deep down, even if you have crises, adversities or difficulties. That is there and that is, in my opinion, the primary objective of any religious experience. And that is achieved by finding yourself in the silence of desire, of aspirations, as Buddhism says, but at the same time with that first or last substratum that we can call divinity.

Why do we always feel happy or have a sense of satisfaction when we find something that was our home, our family, our homeland? Because meeting the root is the ultimate experience of well-being, and that ultimate root is our Creator.

Pressenza: One last message for any human being who is in search of…

Pablo d’Ors.– Look lovingly at your shadow.

And Arash acknowledges: I like Pablo’s phrase, I couldn’t improve it.