Those who went to vote on Sunday did so in the conviction that they would have to return to the polls to decide between the two candidates with the highest number of votes. The polls, and not the popular demonstrations, had decided on the names that were likely to go to the next ballot and the press and public opinion were satisfied with these predictions which, as is well known, are not very accurate in Chile. Practically from the beginning of this short competition, some candidates were taken for granted and those who were considered to have very little chance were relegated to the sidelines.

Citizens learned almost at the last minute that the candidates had government programmes and it was certainly not these proposals that motivated voters. It was a campaign focused on names rather than parties or ideologies. Nor did the candidates arouse the popular fervour of other contests in the past, so much so that many said they should vote for the one who looked the least bad. This is fully explainable by the enormous discrediting of politics and the lack of credibility of its parties and caudillos.

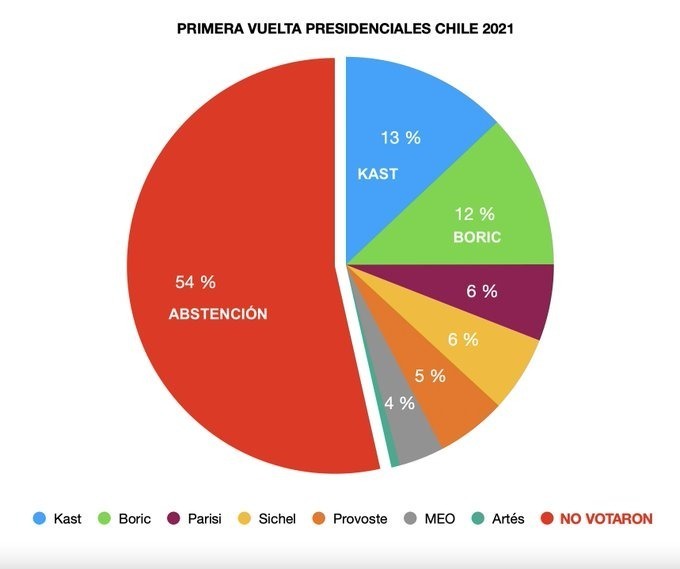

Hence, the abstention levels (52%) were once again high for a country that prides itself on democracy and the high civic spirit of its population, which suggests, in any scenario, that the next president will not obtain the effective support of more than 25 or 30 percent of Chileans with the right to vote. We will have a minority government, with a parliament that will not be very docile to it, and with an enormous amount of social expectations that will most likely reignite social protest. With the aggravating factor that the pandemic is not at all under control, that the fiscal coffers are simply not enough to resolve all the demands that are still pending, and with a legislative branch that will find it hard to agree to whatever the executive proposes.

All the candidates were warned that, if they won, they would have a hard time governing. Just as it would be too difficult for them to deal with the conflicts in various parts of the country, especially in Araucanía. That the phenomenon of violence and delinquency that really plague the country could hardly be mitigated without the possibility of making effective progress in social justice and equity, concepts that from mouth to mouth are positioned in all discourses from the ultra-right to the extreme left. Without a resolution, as a matter of urgency, to drastically improve the incomes of workers and families. Without the new authorities resolving to put an end to the abusive AFPs, to drastically raise the floor of pensions and to stop health care from being the lucrative business of the isapres in order to guarantee medical and hospital care for the whole nation. In other words, what has been promised across the board for the last three decades, without any progress and with the aggravating circumstance that, in order to alleviate the crisis, the meagre funds of future retirees would have to be tapped, making their expectations of a dignified retirement even more uncertain.

With one known exception, no candidate promised to seriously review defence spending, which gives rise to glaring inequality between uniformed and civilian personnel. There was not even any talk of reducing arms purchases, just as there was little mention of the countless cases of corruption among officers and police. Nor was there any promise this time to abolish VAT on books, a long-standing demand that has been flouted by all governments. Thus, the debate on the country’s destiny seemed at times to be confined to the possibility of passing a new and more permissive abortion law, to giving more legal recognition to same-sex relationships and to other issues that, while important, are not really on the agenda of a population that is experiencing so much socio-economic deprivation and is now terrified of the inflation that is making itself felt and could well lead to social explosions in the near future.

It was said that the country was highly polarised, that we were in danger of choosing between a National Socialist and a Marxist-Leninist, to the extent that the centrist candidates did not show much success in appearing to be moderate and winning over those Chileans still shocked by the Pinochet dictatorship and what they have been told about the horrors in Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba. For which the press, addicted to the system, lies and exaggerates through its ignorant and uninformed analysts, as well as the television presenters themselves.

What is certain is that beyond their “commonplaces” and specific and demagogic proposals, all the candidates, with one known exception, went on ad limina visits to the big businessmen and, beyond the cameras, even held suspicious bilateral talks with them that were not noticed by the press. Some went to kneel before the businessmen and others in the hope of sensitising them to the country’s social urgencies, above all to obtain resources to finance their campaigns. There was no talk of expropriation or of taxing them with the fair taxes that are now becoming imperative. And they were only half-heartedly reproached for their new acts of collusion and tax evasion or avoidance. Even less were they called upon to strengthen trade unionism.

There were even candidates who in the past have spoken out against the rule of the market who this time remained sacrosanctly silent and, in the hours before the election, the government decided to scrap a public tender won by a Chinese and German group to make our identity cards and passports. Nothing more than to please the United States, a power that was certainly annoyed and from which reprisals were feared in the face of a sovereign Chilean act. All this despite the fact that the Asian nation is our main trading partner.

To the above, let us add that even the expression “neoliberalism” disappeared from the speeches and presidential debates, with the exception of one candidate who dared to say anything and everything, knowing that he had no chance of reaching La Moneda.

There will now be a second round in which fears will be exacerbated, disqualifications will rise and the candidates -Kast and Boric- will do everything possible to win the support of the losers, who together had more votes than each of their opponents in the second round. We will be told of the danger posed by the victory of the adversary and we will be taken back to the time of Pinochet and the Cold War, when the vast majority of voters did not live through those times and in some cases have only hearsay knowledge of what happened so many decades ago.

However, it is highly unlikely that the new President can really usher in a “new era” as promised and, barring the usual stock and dollar price fluctuations, all indications are that the country will continue to be governed by the political class, with the sacrosanct market remaining our sovereign. With the backing of the rulers and the military caste or praetorian guard. But now a process of negotiations will be imposed by the elite, which could wipe out some of the good intentions with its elbow.

What will happen in the Constituent Convention is another matter, if there is to be any confidence that it will be able to continue to exercise freely in the face of a new and empowered government and parliament, despite its limited representativeness. After an election that, as usual, was highly determined by electoral propaganda, the bias of the powerful media and, it must be said, a country that is very unmotivated about a democracy that does not solve its problems. More unequal, certainly, from one government to the next. More and more convinced every day that it is the street and not the vote that can open its wide avenues.

That is why the enormous majority obtained by the independent candidate, Fabiola Campillay, one of the most severe victims of Piñera’s repression, is so encouraging.