We transmit to you the study “Some clues for nonviolence” carried out by Philippe Moal, in the form of 12 chapters. The general table of contents is as follows:

1- Where are we going?

2- The difficult transition from violence to nonviolence.

3- Prejudices which perpetuate violence.

4- Is there more or less violence than yesterday?

5- Spirals of violence

6- Disconnection, flight and hyper-connection (a) Disconnection.

7- Disconnection, flight and hyper-connection (b- Flight).

8- Disconnection, flight and hyper-connection (c- hyper-connection).

9- The different ways of rejecting violence.

10- The decisive role of consciousness.

11- Transformation or immobilisation.

12- Integrating and overcoming duality and Conclusion.

In the essay dated September 2021, the author expresses his thanks: : Thanks to their accurate vision of the subject, Martine Sicard, Jean-Luc Guérard, Maria del Carmen Gómez Moreno and Alicia Barrachina have given me precious help in the realisation of this work, both in the precision of terms and ideas, and I thank them warmly.

In the essay dated September 2021, the author expresses his thanks: : Thanks to their accurate vision of the subject, Martine Sicard, Jean-Luc Guérard, Maria del Carmen Gómez Moreno and Alicia Barrachina have given me precious help in the realisation of this work, both in the precision of terms and ideas, and I thank them warmly.

Here is the seventh chapter:

Disconnection, flight and hyper-connection.

b- Flight

The neurobiologist Henri Laborit showed, 35 years ago, how flight – disconnection from a problem – is often the way out when faced with something beyond our control. For Laborit, flight is not cowardice, but a response to the forbidden, the impossible, the dangerous. He was referring to the sailor who fled from the storm, not out of fear, but out of survival instinct. We can add that today there is a tendency to flee from what is going too fast and what has become too complex in society, because we do not know how to respond to it.

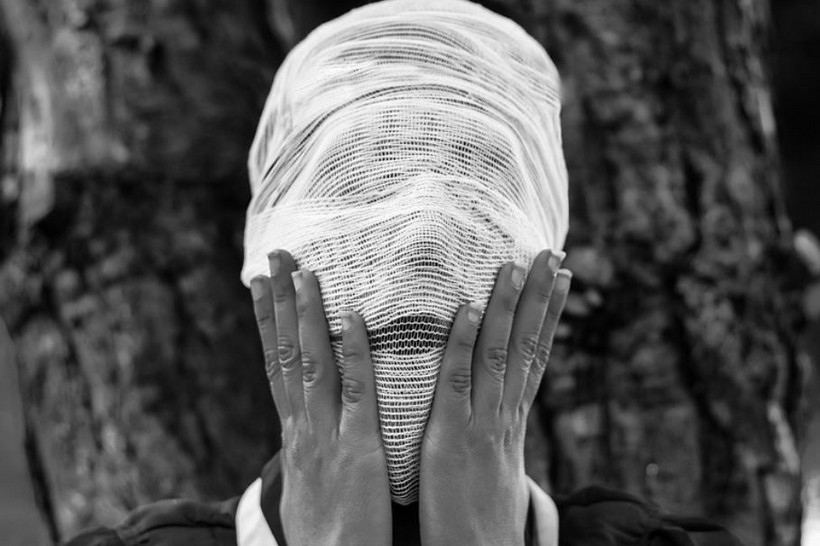

But when the world of men forces me to observe its laws, when my desire is thrown headlong against the world of prohibitions, when my hands and legs are imprisoned in the implacable shackles of prejudice and culture, then I tremble, I moan and I cry. Space, I have lost you and I return to myself. I lock myself in the top of my bell tower where, with my head in the clouds, I make art, science and madness[1].

To hide the unbearable, to flee from the pain and suffering of today’s world, that is, to face only what concerns us, we are being channelled towards escapes that tend to become globally uniform: consumerism, major cultural and sporting events, video games and networks, or television series which, being hyper-violent, can make us feel by comparison that the real world we live in is not so violent (which is perhaps also the aim). These escapes allow us to escape and become real addictions, such as those related to alcohol or amphetamines.

Sartre defines anguish as the feeling of vertigo that invades man when he discovers his freedom and realises that he alone is responsible for his own decisions and actions. (…) It is in order to escape from the anguish that nestles in freedom, to evade the responsibility of choice, that men often resort to those forms of self-deception that constitute the behaviours of escape and excuse, or to bad faith hypocrisy, when conscience tries to lie to itself, mystifying its motivations and masking and idealising its ends[2].

However, despite these diversions, nothing can compensate for the growing economic problems, health difficulties and increasingly precarious living conditions of a growing number of people.

As for the forgotten who live in alarming living conditions, they no longer count, they are on the margins, they are redundant for society; they are in the same boat as those who live in areas where there is war, famine or any other serious situation: for them there is no escape, there is no palliative, only survival counts.

In a lecture[3] in 1975, Silo described how escape from consciousness is impossible because the intentional act-object structure is present in consciousness, come what may, unless it destroys itself.

I summarise here, in lapidary fashion, some points of his analysis: “In the state of escaped consciousness, there can be no self-consciousness, escape is attempted through the increasing stimulation of the senses. As escape from reality is the real concern, everything becomes imaginary and happens in the head and nothing will actually be done to change the oppressive situation, because the priority is to escape from it. In the state of escaped consciousness, everything becomes illusory and is translated into ritualistic acts to make sense of what is being done. As consciousness and the body cannot be separated, the latter can somatise. Disconnection from oneself and from the world cuts off all possibility of communication and there is no more intersubjectivity, no more self-criticism. The only possible way out becomes almost magical; in politics, for example, any charismatic candidate will be the saviour who will make it no longer necessary to flee, who will fulfil everyone’s wishes…” A cruel illusion!

The only way out of the fugue state of consciousness is to return to oneself. By refocusing and reconnecting with oneself, one returns to the essential. While one was outside oneself, it is a matter of going back inside oneself, realising oneself, recognising oneself.

Just as one flees from poverty, illness and loneliness, just as one flees from these sources of suffering, the flight from life and the flight from death are inherent in today’s world, whose values are underpinned by individualism, nihilism and immediacy, leading inevitably to existential meaninglessness.

Until I realise that I am living and until I realise that I am going to die, I am condemned to live in violence. The two realisations are closely linked; one cannot exist without the other. I cannot live serenely if I forget my death and I cannot live fully if I do not realise that I exist.

Not being aware of myself, existing, forgetting myself in a certain way, leads to a life of an automaton, mechanical, instinctive, impulsive, hypnotised by the outside, illusory, dominated by the body…, a state that leads directly to violence.

Not realising or forgetting that I am going to die leads to meaninglessness, to absurdity, to nihilism, to the secondary…, a state that leads directly to violence.

Why do we run away from death, is it because we are afraid of being afraid, is it because of a lack of questioning and reflection, is it because of the anguished doubt about the after death or the after life? Paradoxically, the more I accept to consider my death, the more I allow myself to look it in the face, the closer I get to it, the more I tame it, one might say, the less anguish it causes me, the less it terrifies me and the more it becomes part of my inner landscape.

When his beloved brother dies, he contemplates death for the first time with spiritual eyes, and is horrified. As a sincere man, with extraordinary frankness, he admits that he is defeated by it, that he is insignificant before its power. And this truth saved him. From that moment on, it can be said that the thought of death never left him. It led him to an inevitable moral crisis and to victory over it[4].

Why this flight from life? Perhaps because I am absorbed by the outside world, more concerned with doing than with being; perhaps also because I forget the aspirations and ideals from which all my activities start; perhaps to keep myself busy and not to glimpse my inevitable death.

Living with the awareness that I exist makes me connect with myself and with the world simultaneously. I am aware of the other person, so violence against them is inconceivable. Better than that, with this gaze I experience feelings of compassion, protection and closeness with him. We are one, connected to each other, out of the state of indifference that separates us, which is above all an indifference to myself.

By incorporating a new gaze with which to contemplate my own death, I recognise that one day the body will cease to function, I will have to separate from it and therefore free myself from it, and continue on my way. When I am aware that I am going to die, I am aware of the death of the other; this brings us closer, we are both in a temporary, ephemeral situation. Being similar, what can we do together that is constructive, how can we help each other instead of destroying each other? The realisation of the other’s death brings me closer to him while he is there, while I am there. What can I express to him? What can I do for him? What experience can I pass on to him? The realisation that the other person is also going to die invites me to do with him/her everything I will not be able to do afterwards, because it will be too late.

Accepting to see my death gives me a register of freedom, that of breaking down the barriers, prohibitions and limits that prevent me from listening to, seeking and putting into practice my deepest aspirations.

When I stop from time to time in the course of my daily activities, even if only for a moment, to connect with myself and humbly and honestly ask myself these fundamental questions: Who am I? Where am I going? I become aware that I exist, as well as my finitude. These are questions that, among other things, lead to non-violence.

Notes

[1] Éloge de la fuite (In Praise of Flight), Éditions Robert Laffont 1976, p. 184, Henri Laborit (1914-1995), French surgeon, neurobiologist and philosopher, popularised neuroscience among the general public.

[2] Interpretations of humanism, Virtual Editions, 2000 (© 1997), p.73, Salvatore Puledda (1943-2001), scientist, thinker and humanist writer.

[3] The Flight of Consciousness, apocryphal talk, Silo, 1975.

[4] Leo Tolstoy, Life and Works, Pavel Ivanovič Birûkov (1860-1931), Russian writer, biographer of Tolstoy, Mercure de France, 1906, p. 120.