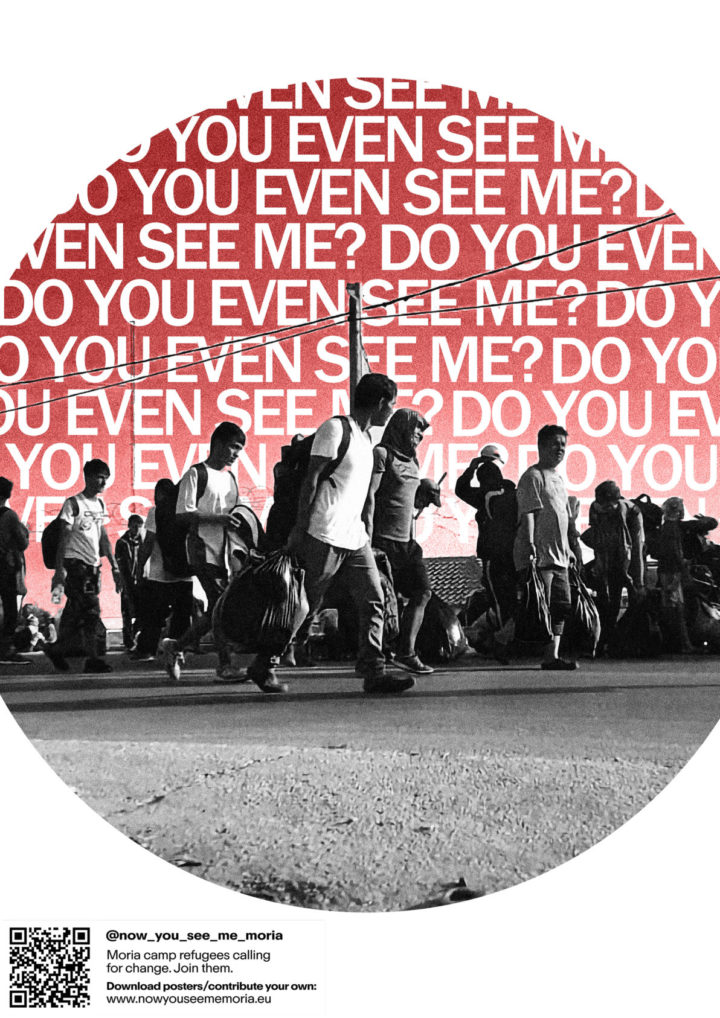

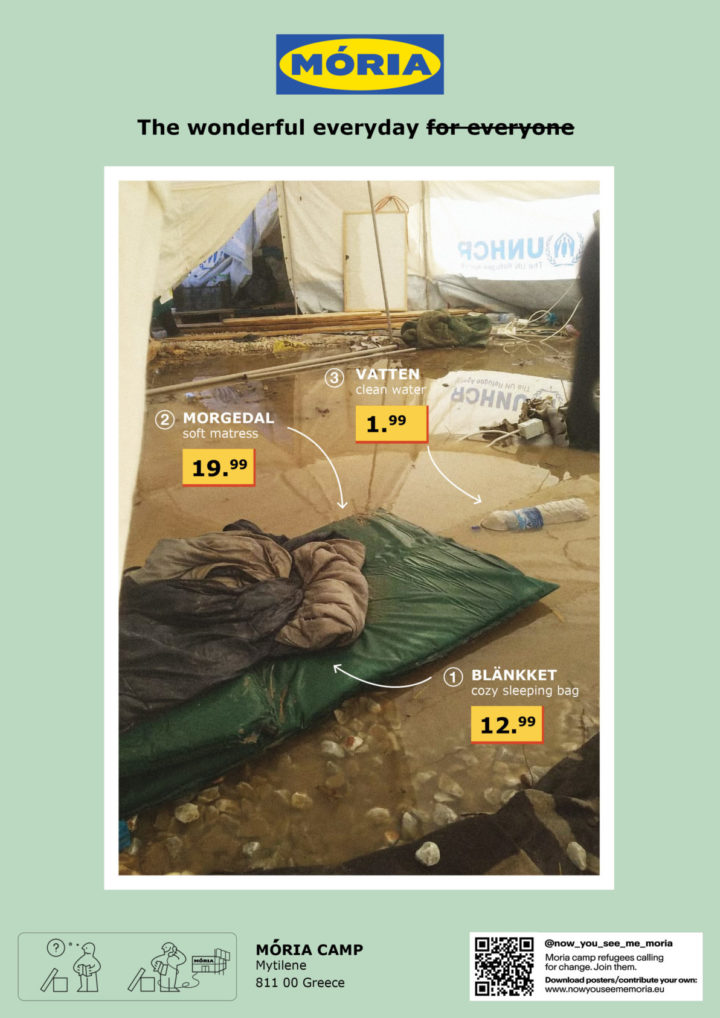

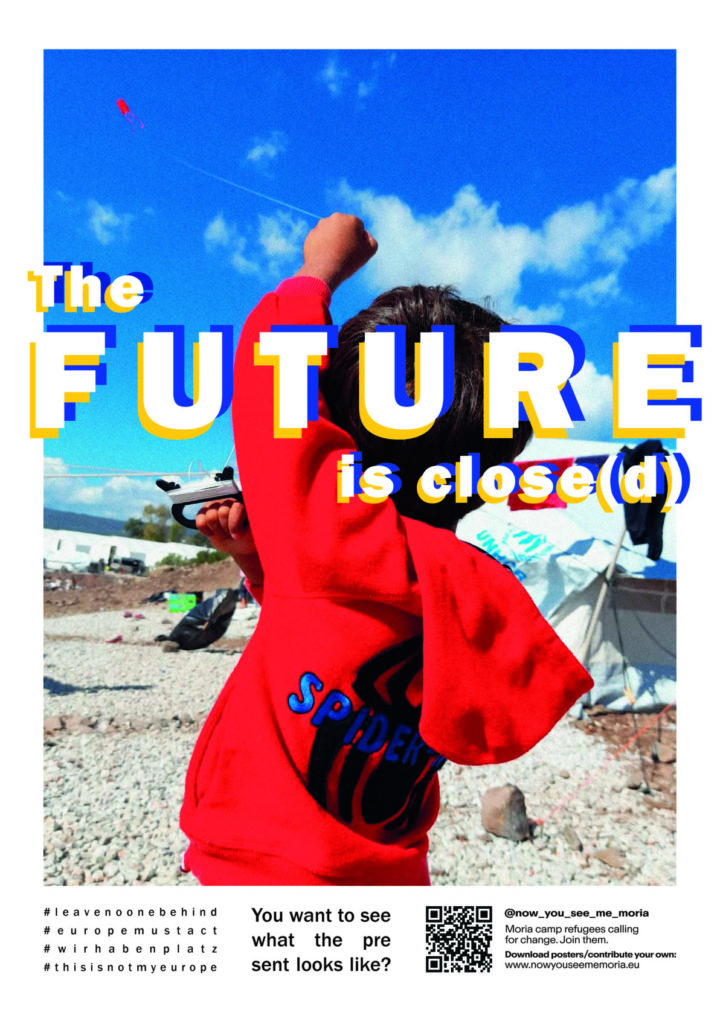

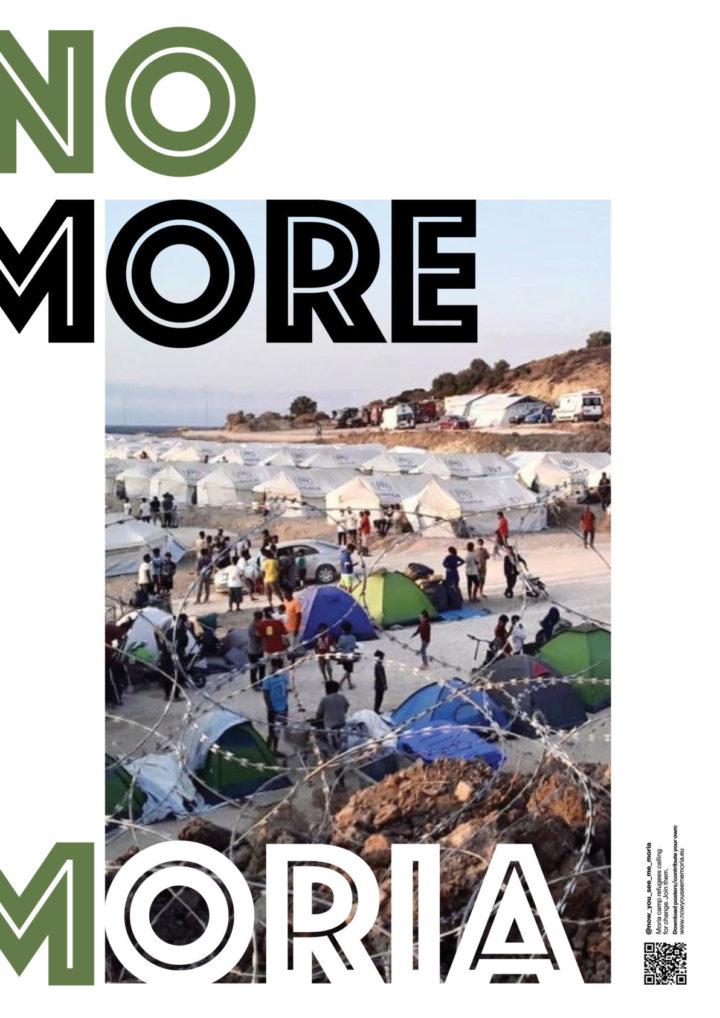

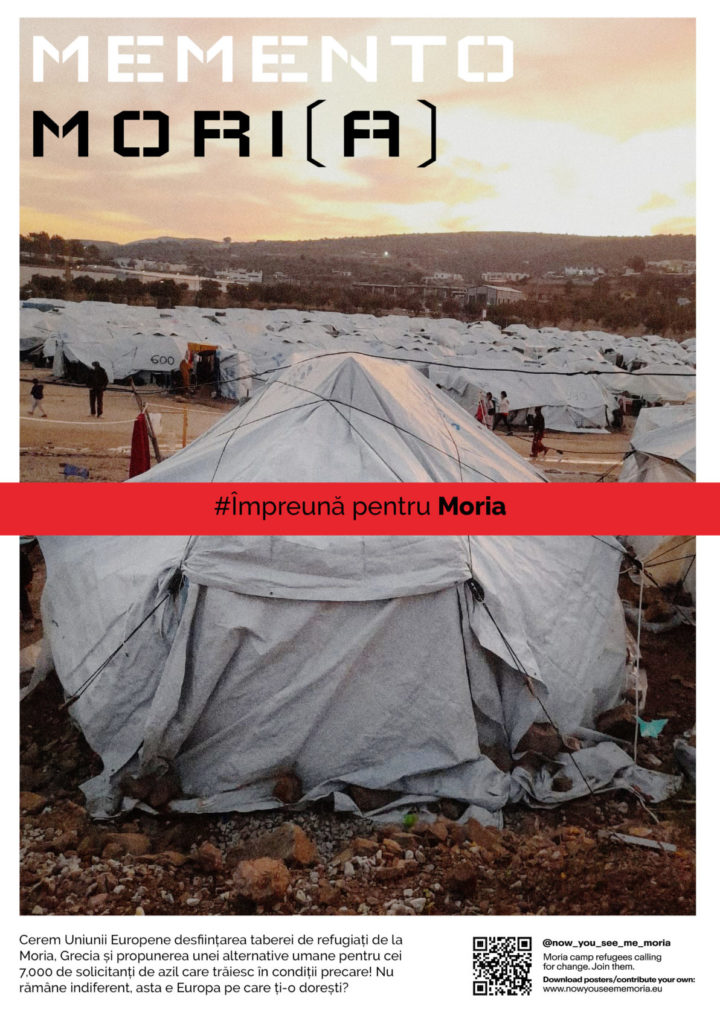

Last week we met Noemi from the collective team of “Now You See Me Moria”, a collaborative project that seeks to raise awareness of the situation in Moria and an urgent appeal to policymakers to change failed immigration policies. The program with main vehicle photos from everyday life in the refugee camp of Mytilene “Moria 2” invites designers and citizens to download the posters and post them in a public place in their city. Images from “Moria 2” last months have traveled on posters in many cities around the world, such as Munich, Cologne, Berlin, Seoul, Antwerp, Vienna, Dusseldorf, Brighton, Olten, Grantz, London, Geneva, etc.

What was the inner motivation for you to start this project and what was the first reaction of your friends?

One night just checking my social media in Facebook, following a friend who is an Afghan journalist, and he was living for 5 months in Lesvos, making a movie about the situation in Moria during the pandemic. And there I saw some photos from Amir and those photos attracted my attention because they were very different to the typical photos that you can see about migration and about refugees.

I was very touched by the photos and I realized that he was trying to express something. And that is how I contacted him, and told him that I think these photos were very strong about the reality of migration and I told him maybe we can start this collaborative project together. We can combine the photos he was taking with my knowledge about photography and then together we can try to bring out what’s happening in Moria so that more people can see and know what is happening. It was a moment that we were also focused on the pandemic in our countries and there was really nothing in the news about the situation in Moria.

At the beginning, my friends, did not thought that we were doing something important, but now they realize that it is important. Because you meet more people that realize that you could do something about the situation by not accepting people living like this. There is a general approach that this is how things should be, to be treated like this and that’s okay. I think there was a common feeling of accepting this situation, that “we cannot do anything,” “it is not in my hands,” “there is nothing I can do.” Politicians are responsible for migration policies and you as a citizen you have also responsibility by not accepting this behavior anymore.

I think that the most important thing is to change our mindset. We are not going to accept any longer that people are treated that way, like in the past when women could not vote. It is happening all across Europe and we cannot accept it anymore, and we all can do something. Many thousands of people together, we can bring a change, it would be a big step.

This initiative is by a group of people and every time we are trying to engage more people, like graphic designers, graffiti artists for 18th of March, in order, to create some murals with criticism of the EU-Turkey deal, because on that day is the 5th year anniversary. Also political scientists are engaged and also journalists, like you that you give the opportunity of making an article in Greek.

This concept that refugees are dangerous it is not real. We can see photos at the media mostly of people arriving with boats and when they pray. And the clear message when you portrait refugees arriving with boats, you portrait them as a threat, as if they are making an invasion. It is all about visual culture and how refugees and migrants are represented. And, also, you will see a lot of photos of them praying. Well, yes, some of them are praying, some of them are Muslims, but others are precisely trying to get away from religion and they don’t pray, they don’t believe. So there is an issue, how the rest of us see them through media as a threat, and there is a political decision behind that. Of course there are people that behave badly, but they are the minority. But this is something that is the same in every society.

In our project, the representation of the situation is made by the people who are experiencing the situation, and not by a photographer. We believe this is important because as a photographer you have your vision when you go to a place, so maybe it is very appealing when they are praying, and you have to be far from judging them. So, when you let the person who is experiencing the situation to represent themselves, then it’s completely different the kind of images that they’re going to reproduce and you are going to see.

With the project you can see the daily life, how it is to live inside a European refugee camp, with all the bad conditions and the daily life too. We show everything. We have for example shared videos where they are celebrating a wedding, or when someone got the status of a refugee and is happy. And I believe this brings more closeness of the people instead of feeling fear. Instead of focusing at the differences, it focuses in the things that they have in common, like they want to see their children go to school and study, to have a house to live, to have a job and to have a safe life and not being in this constant uncertainty on what is going to happen.

Especially you have to think that 40% of the people in Moria refugee camp are children. And all of those children have no access to education at the age of 12, 13, 14 or 15. You cannot

have children for 2 years without access to education. That is a crime. And I do not think that money is the issue, with all this quantity of NGOs and donations from people. The problem is that they don’t want to do it because it’s a message. It’s like “if you come, we are going to treat you bad, so, don’t come.”

But we, as Europeans, we cannot accept that they are being treated badly. Of course there should be some kind of system, but a humane one that respects humans, and we cannot let people die at the sea, and the people who arrive cannot be treated like this. Because at the end of this nightmare, some of them will get the refugee status, but the mental damage is done. Staying in these conditions for 2 or 3 years, creates a lot of mental issues after, it changes you.

What are the main obstacles that you have faced up to now?

They want to use, always, photos taken by professional photographers. Like the incident with the fire. Of course the people get interested, but then they forget the game. And with the media it’s complicated.

Also, creating the images it’s not easy, because they have to do it in a very careful way. It has happened two times, that the police saw them taking photos and then they broke their phones and so they have to be very careful.

Also, for them is not that easy, when they have taken the images sometimes they don’t feel comfortable, they are all day in a tent. Imagine your situation, working at home with children, but at least they have the option to go to school online and you are at home working. But they are not in the same situation. They are inside a small tent, sharing it with another family, separated with a blanket. All this with cold and rain, and not knowing when this is going to end. Because, when there is a difficult situation and you know that this is going to end in a month, then, mentally, you have a bigger persistence because this is going to end. But they don’t know how more they have to wait and stay under these conditions.

Has the initiative found support at local and institutional level in any European country?

We didn’t have any institutional support but lot of support from the graphic designer Raoul Gottschling, Linkelab from Milan and Bas Vroege director of Paradox from Rotterdam.

What are your next steps?

On 18th of March, the 5th year anniversary of the EU-Turkey common statement, we are going to share the posters with the European civil society platforms “Europe Must Act” and “Leave no one behind” which were very supportive.

For more information about the project you can visit www.nowyouseememoria.eu