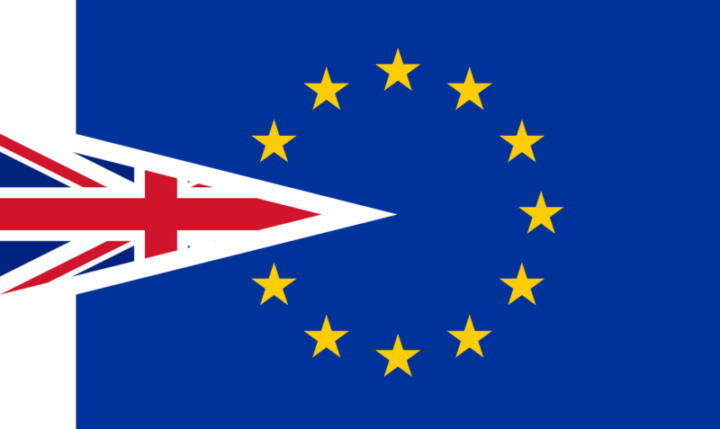

The political conflicts between the EU and Great Britain – also over vaccines – are increasing while economic ties are decreasing.

The controversy between the EU and Great Britain over access to Covid-19 vaccines is escalating. The persistent EU campaign against the vaccine by AstraZeneca (headquartered in Cambridge) has already provoked considerable anger in the UK. Brussels’ threat to withhold future vaccine supplies from Great Britain is further exacerbating tensions. Recently, the EU ambassador to the UK was summoned to the Foreign Office by British Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab. Brussels, on the other hand, has launched legal proceedings against London over a breach of the Brexit deal’s Northern Ireland Protocol. While political tensions are rising, economic ties are diminishing – apparently a long-term trend. Experts forecast that overall UK trade with the EU could fall by about a third by 2030. At the same time, the UK is rapidly expanding its economic ties to Asia – and plans to shift the focus of its foreign policy to the “Indo-Pacific.”

Campaign against AstraZeneca

The persisting campaign within the EU against the vaccine by AstraZeneca (headquartered in Cambridge) is provoking considerable anger in the UK. The Union and several member states, including Germany, have strongly attacked the company for delivery delays, initially imposed age restrictions for application of the vaccine, and have regularly downgraded its somewhat lower efficacy compared to the vaccine from BioNTech/Pfizer (Germany/USA). Recently the use of the AstraZeneca was suspended due to uncertainties related to several cases of thrombosis following vaccination. The EU’s complaints are causing all the more anger in the UK since the delivery of other vaccines (BioNTech/Pfizer, Moderna or Johnson & Johnson) have also repeatedly been delayed and have produced side-effects – including blood clots – occasionally resulting in death, without encountering comparable attacks. After a while, the AstraZeneca age restrictions had to meekly be lifted. The EU campaign has, however, seriously damaged the reputation of the British vaccine that was recommended by the WHO and is also produced under license by the Serum Institute of India (SII) for many poorer countries.

Summoned to the Foreign Office

The EU has also been exacerbating tensions by now resorting to export bans, in an attempt to divert attention from its failure to procure vaccines. AstraZeneca and the UK are again being targeted. The first such case (March 4) was met with massive protest worldwide. In collusion with the EU Commission, Italy had blocked export to Australia of 250,000 AstraZeneca jabs – produced in Anagni south east of Rome – declaring the EU needs the vaccine itself. (german-foreign-policy.com reported.[1]) Because the EU campaign against AstraZeneca has considerably reduced the vaccine’s reputation within the population, eight million jabs are currently stockpiled in warehouses around the EU.[2] In response to the Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen’s most recent threat to ban vaccine exports to the UK, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab said that normally this “kind of brinkmanship” is only known from “countries with less than democratic views.”[3] Previously Raab had summoned the EU’s UK representative to the Foreign Office, because of the false claim, persistently repeated in the EU that London has banned exports of vaccines.[4]

Dispute over Northern Ireland

The EU’s attacks on AstraZeneca and the British vaccination campaign have horrified and outraged even the previously EU-loyal “Remain” milieus and weakened the Union’s standing within Great Britain. Now the dispute over supplying Northern Ireland with British commodities is escalating tensions. According to the Brexit agreement, some of the rules of the EU’s internal market still apply to Northern Ireland, but not to Great Britain, after it withdrew from the Union. This means that commodities being delivered from the UK to Northern Ireland must be inspected, to determine, if they conform to these rules. This is posing serious practical problems, particularly for the delivery of foodstuffs. Since discussions with Brussels have not yet resolved this problem, London has extended the grace period – due to expire at the end of March – to the end of September, to prevent empty shelves in the supermarkets. The EU considers this a breach of the Brexit deal’s Northern Ireland Protocol and has launched infringement proceedings before the European Court of Justice (ECJ). Maroš Šefčovič, Vice-President of the EU-Commission complained that London “undermines trust between us.”[5] Infringement proceedings are not uncommon in the EU. By mid-2020 for example, 81 such proceedings were pending against Germany alone.[6]

Asia-Pacific Growth Region

As political tensions are increasing, Great Britain’s economic ties to the EU are decreasing. This apparently is a long-term trend. For example, the EU-27’s portion of British exports in goods and services has been declining since 2002, when it had reached its historical peak of 54.9 percent. In the year preceding the crisis – 2019 – it was only at 42.6 percent. The EU-27’s share of British imports is also on a long-term downward spiral, since it reached its high point of 58.4 percent in 2002, to reach 51.8 percent in 2019. Conversely, trade with non-EU countries is becoming more significant for the United Kingdom – a tendency that is increasingly winning over sectors of the British elite to support Brexit. Over the past few months, London has entered free trade agreements with Japan as well as with several countries in Southern Asia, and is seeking a free trade agreement with India. It intends to focus more intensively on the Asia-Pacific region, which is already the region with the greatest share of the global economic output (35 percent) along with being the region with the fastest economic growth.

Disintegrating Sales Market

The fact that, the EU’s importance for the British economy is diminishing, in the long run, primarily affects German industry which, by far, had been Great Britain’s largest supplier on the European mainland. Prior to Brexit, in 2015, the United Kingdom had been the third-largest customer for German exports, after the United States and France, (with a volume of €89.2 billion). In the year prior to the corona crisis in 2019, German exports to the British Isles had only reached €79 billion – a drop of ten billion, even though German exports, in general, had significantly increased within the same timeframe. The decline is only partially due to the devaluation of the pound in relation to the euro. For the month of January, (the first month, when the post-Brexit free trade agreement between the EU and Great Britain went into effect), Germany’s Federal Office of Statistics announced a dramatic slump of 29.0 percent in German exports to the United Kingdom and a slump of even 56.2 percent in imports in comparison to January 2020.[7] The Corona crisis and problems of transition have played a role after the regulations of the transition period ended, however, a recent study commissioned at the London School of Economics (LSE) predicted that overall UK trade with the EU could fall by about a third over the next decade, under the new trading terms.[8]

Shift to the “Indo-Pacific”

Great Britain’s economic reorientation is being accompanied by a shift of the political paradigm, outlined in a strategy paper presented Tuesday by Prime Minister Boris Johnson. The paper (“Global Britain in a competitive age”), drafted in the course of last year, particularly proposes to shift the focus of Britain’s foreign policy to the “Indo-Pacific” region, which London considers to be the new center of global policy. In light of the West’s power struggle with China, the paper calls for closer cooperation with regional pro-western governments and modernization of the British armed forces, particularly the naval forces.[9] Experts are already discussing how the UK’s shift to Asia will affect foreign and military policy cooperation with the EU, which is of principal importance for Germany – particularly for being able to use the clout of Britain’s armed forces in future EU operations. (german-foreign-policy.com reported.10]). Some already doubt that there will be enough converging interests in the future.

[1] See also Europe First.

[2] Jakob Blume, Thomas Hanke, Hans-Peter Siebenhaar, Christian Wermke: Stopp für Astra-Zeneca: In der EU wird Impfstoff zur Mangelware. handelsblatt.com 17.03.2021.

[3] Kate Devlin, Tom Batchelor, Jon Stone: Raab compares EU to dictatorship as row over access to vaccines escalates. independent.co.uk 18.03.2021.

[4] Jessica Elgot: Raab summons EU official as anger grows over UK vaccine export claims. theguardian.com 09.03.2021.

[5] Verfahren gegen London. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 16.03.2021.