In 2008 progressives lacked a coherent and compelling alternative to neoliberal policies. This time it must be different.

“Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.”

Milton Friedman understood that moments of crisis do not automatically create change. They are shaped by politics. When the global financial crisis hit, it was neoliberal ideas that were ‘lying around’, and their exponents who successfully framed the causes and solutions. Progressives lacked a coherent and compelling alternative.

As a result, the policies employed in the UK over the past decade have damaged the living standards and services of ordinary people, and have not addressed long-standing weaknesses in our economic model – indeed they have exacerbated some of its worst features. The challenge for progressives today is to show there really is an alternative, and not just be content ameliorating the failures of the status quo without shifting the parameters. When the crisis comes, we have to be ready with an agenda for transformation.

Last year, IPPR’s Commission on Economic Justice set out a ten-part plan for fundamental reform of the economy to match the scale, if not the direction, of the last great shifts in how we organise our economy and for whom: the post-war moment, and the neoliberal counter-assault from the late 1970s onwards. Today, we’re launching the Centre for Economic Justice to take forward that agenda and create a coherent policy programme for a fairer and stronger economy.

The case for change is clear. The UK economy is not delivering. Employment growth since the financial crisis has been accompanied by the weakest decade for average real earnings growth in 200 years. Over the last 40 years, only 10 per cent of national income growth went to the bottom half of the income distribution. The UK is Europe’s most geographically unbalanced economy, with wide disparities in wealth and power between nations and regions, and once-thriving communities suffering economic decline. These problems are not glitches in an otherwise healthy system; they are the result of structural flaws in our economic model.

For the past three years all attention has been turned inwards to the Brexit process. But new risks in the global economy, as well as deep shifts in how we will produce and distribute goods in the future economy, mean we must now look outwards.

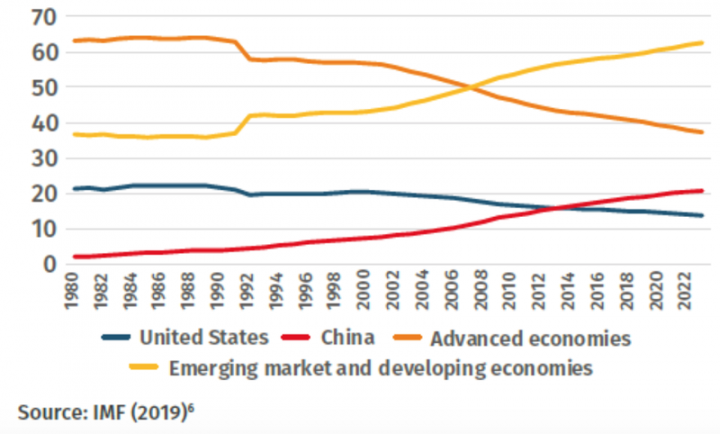

There are good reasons to prepare for instability and a potential recession in the years ahead. While the largest contributor to global growth is now China (see figure 1), its economy could be running out of steam. Debt has risen in China and many advanced economies: if monetary policy is tightened, as expected, this could become unsustainable. Political uncertainty in the Eurozone and escalating trade wars pose further risks. While by nature economic shocks are unpredictable, the UK should be prepared: post-war history shows us to expect a UK recession every 10-15 years.

Figure 1: Contributions to global growth (GDP based on PPP, share of the world)

More fundamentally, the very systems upon which our economic model relies – the Earth’s natural systems – are being increasingly damaged by our activity and systematically unaccounted for in investment decisions across the globe. Climate change poses risks to the stability of our financial system, future economic activity and productivity. Business-as-usual is no longer an option: the question is when, not if, we shift to a less extractive model.

So too, technological change demands a reimagining of our economy. Technological change is changing the shape of production, where it can occur and who captures the gains from growth. Managed well, there are huge opportunities in change; managed poorly it risks exacerbating existing inequalities of power and reward.

The UK has agency in the global economy, particularly given the City of London’s prominent role in the international financial system. Brexit, and how it is handled, will shape our economy and other economies for years to come. We have shown climate leadership in the past and can do so again in future, to match our historic responsibilities and present capabilities. But many of these shifts are occurring outside the influence of UK unilateral and domestic political institutions. Yet while policymakers may not be able to control the changing global economy, they can choose how to prepare and how to respond. Proponents of progressive policies must be ready to shape this response.

That will mean arguing for macroeconomic policies that protect the economy from risks, such as macroprudential policies to help direct investment into the productive economy and prevent bubbles forming. It will also mean arguing for coordinated macroeconomic policy that targets not just stable growth, but equitable outcomes. Over the past decade, fiscal and monetary policy have pulled in opposite directions, with austerity stripping demand from the economy and severely undermining public services, while Quantitative Easing has benefited the wealthy by pushing up asset prices. With interest rates still near their lower bound, alternative measures will need to be used and this time the impact of the response on wealth, and who the response benefits, must be considered.

It will also mean addressing the long-standing weaknesses of the UK economy, in particular low investment, a trade deficit and poor productivity. Succeeding in the global economy of tomorrow will mean shaping our economy to respond to environmental breakdown and technological change. Far from avoiding robots, we need more of them: but this process must be managed to ensure the rewards are widely shared. So too the UK should radically and justly decarbonise its economy, to generate green, high-quality jobs

From the Wall Street Crash to the global financial crisis, history shows us that policy responses to crises shape not just the stability and level of growth, but also levels of inequality in society, who holds economic power and how people feel about their futures. The consequences of the progressive failure to set out an alternative and coherent response to crisis is all around us in the vote for and repercussions of Brexit. The irony is that Brexit has caused politicians to look inwardly, when what is needed is a vision for the economy of the future, in a global context. That economy must be one in which prosperity and justice go hand in hand.