By Jeffrey Lawrence

On September 19th, 2011, Luis Moreno-Caballud and Begoña Santa-Cecilia returned to their apartment after three days of intense discussions and assemblies in New York City’s Zuccotti Park. As members of Occupy Wall Street’s original Outreach Committee, they were frustrated by what he had seen in the park since the beginning of the occupation on September 17th. They had imagined that the encampment in the heart of Wall Street would be something like the acampadas they had visited in Spain earlier that year, large open tent camps in public plazas where diverse groups of people had congregated. Yet it still wasn’t happening. Zuccotti Park was ringed by police vans, protestors in bandannas yelled at officers and passerbys from the sidewalk, and the assemblies themselves had become fractious. They decided to send an email to the Outreach Committee, the “working-group” responsible for communicating Occupy’s message to the outside world, to propose a change in tactics.

The aim of the email was simple. Occupy needed to emphasize that it wasn’t just another demonstration of protestors violently decrying the “system,” but a movement that was creating a physical and conceptual space where people could come together to talk, to listen, and to formulate alternative solutions to the global economic and political crisis. Rereading emails and thinking back over assembly debates, they revived a slogan that had been formulated through collective process in the days leading up to the occupation: “We Are the 99%.” Moreno-Caballud sent the email with the subject line “#OccupyWallStreet stays alive by becoming #WeAreThe99%:”

It looks like #OccupyWallStreet is in urgent need of a massive and targeted outreach operation to stay alive. The key to the success of the movement is to be inclusive. Right now the movement is too homogenous, due to the ‘activist’ imaginary and language identified with it…I propose that we start today a fast and massive outreach campaign with this idea: #WeAreThe99%. This is the plan: we put all our energy and resources in outreaching for the #WeAreThe99% Day which will happen next Saturday 23rd, at our space in Zucotti/Liberty Park.

Two days later, Justin Molito, another member of Outreach, began to print flyers. By that weekend, the 99% campaign was on the ground and #WeAreThe99% became a trending topic on Twitter. Within two weeks, encampments had gone up in more than fifty cities in the United States. “We Are the 99%” was being chanted around the country, then around the world. The 99% movement had gone global.

It is helpful to pause for a moment to recall just how deeply the “We are the 99%” slogan became ingrained in the American national consciousness during the months of October and November, 2011. Perhaps we are still too close to those “Occupy months” to fully comprehend how, in a country that prides itself on speaking to and for the middle-class, the rhetoric of the 99% and the 1% reconfigured our political vocabulary. Indeed, it seems plausible to believe that ten years down the line, those months will be seen as the turning point in the buildup to the 2012 US presidential election—when a beleagured Barack Obama, reeling from the disastrous results of the 2010 midterm elections and a poor performance in the debt ceiling showdown with congressional Republicans, was finally able to strike something of a populist note. How ironic that it was a Spaniard who had sent the email. So how did it happen?

There are a lot of misconceptions about the history of the Occupy movement in the United States. Since the earliest days of Occupy Wall Street, when The New York Times reporter Gina Belafonte referred to the Zuccotti Park encampment “political protest as spectacle,” the mainstream American media has largely presented Occupy as a ragtag group of dissatisfied individuals struggling to find a purpose. At the same time, those sympathetic to Occupy Wall Street have often given an account of the movement’s origins that revolves around the activities of a cluster of American organizers who somehow managed to capture the public imagination. This is a different narrative of Occupy Wall Street. It is a story about how a group of foreigners who brought tactics and experience from recent social movements in other countries articulated some of the most persuasive ideas and lasting practices to come out of the Occupy movement.

The Politics of Anyone and the NYCGA

From August 13th to September 10th, 2011, I attended gatherings of the New York City General Assembly (NYCGA) in Manhattan’s Tompkins Square Park. At these weekly “general assemblies,” which were open to anyone who wanted to join, a group of about fifty or sixty people planned the September 17th encampment in and occupation of Wall Street. The standard narrative of Occupy Wall Street in tells of how the American left was finally able to muster a collective movement to combat the abuses of the politico-financial elite in the wake of the economic crisis of 2008. Even those articles that have recognized Occupy’s international connections have usually characterized them in terms of indirect “inspiration” by the earlier social movements of 2011 in Egypt, Greece, Spain and elsewhere. Yet what I saw at these gatherings, and what I have been able to reconstruct by looking at the early documents of the NYCGA, is that about 40% to 50% of the participants in the assemblies in August and September of 2011 were from places other than the United States: Spain, Brazil, Iran, Greece, Armenia, Japan, India, Palestine, Argentina, Russia, and Italy, as well as the Choctaw nation and Puerto Rico. Only one media piece in the first month of Occupy Wall Street focused exclusively on the international roots of the movement, Andy Kroll’s October 17thMother Jones article, “How Occupy Wall Street Really Got Started.” As far as I can tell, his provocative but legitimate claim that foreign participants were at least as important as Americans in the organization of Occupy Wall Street was not seriously taken up anywhere else. Perhaps more surprising to me has been the way that prominent intellectuals on the left, from Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri to Immanuel Wallerstein, began to rehearse this narrative of indirect inspiration rather than direct participation once Occupy went global.

My goal here, however, is not simply to recuperate the significance of the international participants. From the first days of the NYCGA and the organization of Occupy Wall Street, there were different internal visions of the movement’s aims. Paradoxically, while most interpretations of Occupy have tended to marginalize the foreign voices in the movement, these foreign voices are the ones that have resonated most profoundly with people in the United States and around the world. This is particularly true of the Spanish contingent of Occupy Wall Street, which made up between ten and twenty percent of the small organizational assemblies of the NYCGA. I remember one American commenting in quasi-religious terms of the “unshakeable faith” of the Spaniards, and another (a little less enthusiastically) mentioning the fact that he was one of the few people in the NYCGA, foreign or American-born, who did not speak Spanish. Like Moreno-Caballud and Santa-Cecilia, many of the Spaniards had recently returned from Spain after participating in the indignado or May 15th (15-M) movement, which was launched on May 15th, 2011 with a nationwide demonstration against corruption among the Spanish political and financial elites and led to the construction of encampments (acampadas) in major squares across the country. By July, 2011, 15-M had achieved an 80% approval rate among Spanish citizens, and current estimates suggest that the movement has succeeded in attracting six to eight million people to the encampments in Madrid, Barcelona and various other cities and towns. In addition to the convictions borne of having just witnessed this truly popular movement, the Spanish contingent of Occupy brought an important principle that had been forged in the crucible of the acampadas.

This principle was what the Spanish contingent began to call “the politics of anyone,” (la política de cualquiera), the belief that social movements should be composed of everyone who wants to participate. Although “horizontality” emerged in the autonomist and anti-globalization movements of the 1980’s and 1990’s as a keyword for the consensus-building structure of popular assemblies, the Spanish conception of Occupy was oriented less toward the activities of those internal to these gatherings—“autonomous” groupings engaged in “direct action”—than toward ordinary people outside of the assembly. They were more concerned, that is, with the inclusivity than the horizontality of the movement. For them, a “leaderless” movement was important not only because it established a protocol for non-hierarchical assemblies, but also because it blurred the lines between those on the inside and those outside of the movement. The Spanish contingent often repeated the phrase, “We care less about Occupy itself than what Occupy represents.” They were deeply impressed by the way that activists in 15-M had ceded authority and agency to newcomers just arriving at the acampadas, and they were adamant about the need to frame the movement’s message so that non-activist and non-academics could understand it.

Corollary to this belief, the Spanish contingent held that the encampment of Wall Street should not only be the site of a protest against the excesses of American financial institutions but also, and even more fundamentally, a construction site for an alternative society in which cooperation and mutual support would substitute for economic competition. In many ways, this idea was consistent with the principles of self-organization outlined by fellow NYCGA participant in his now iconic article that originally appeared in The Guardian on November 11, 2011, later republished as “Occupy Wall Street’s Anarchist Roots.” Graeber, perhaps the most visible face of the Occupy movement, has been one of the few activists to recognize the contributions of the Spanish indignados and other international participants in the creation of Occupy Wall Street. Yet Graeber’s recent account of the movement in The Democracy Project: A History, A Crisis, A Movement focuses heavily on the anarchist process of the assemblies, downplaying the initial fears, repeatedly voiced by the Spaniards and others during these gatherings, that an exaggerated emphasis on the internal dynamics of the assembly would create an isolated radical community rather than an inclusive movement. From my perspective, the success of the organization of Occupy Wall Street by the NYCGA owed much to the powerful combination—one could just as easily say the productive tension—between those working primarily inside and those looking primarily outside of the assemblies.

One of the main characteristics that distinguished the Spanish contingent from the rest of the participants in the NYCGA is that most of the Spaniards in the movement had never been activists before the events of 2011. Like the majority of Spaniards at home and abroad, they were drawn to the 15-M movement precisely because the language of the acampadas had moved beyond the traditional discourses of the left. Though many of the Spanish participants in the NYCGA had a postgraduate academic formation—Santa-Cecilia, Moreno-Caballud, Lauren Dapena Fraiz, Ángel Luis Lara, Maleni Romero, Lucia Rey, Vicente Rubio, Xavi Acarrín, and Nikki Schiller—all were captivated by the simple slogans coming out of the acampadas of the 15-M. Nearly everyone at the NYCGA assemblies was steeped in the radical political tradition, and had read everything from Marx and Franz Fanon to Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, from Gayatri Spivak and Jacques Rancière to Hardt and Negri. The fundamental difference, in my view, was how the participants related to these thinkers. While several (though not all) of the American activists couched their anti-capitalist sentiments in the idiom of academic theory, the Spanish contingent was primarily concerned with how the ideas being generated in the NYCGA could be modified, reformulated, and translated into slogans that were understandable beyond the activist and academic community. They were inspired by the Madrid-based writer Amador Fernandez-Savater’s blog posts during the first weeks of the 15-M, when he defended the political potency of ordinary language statements such as “real democracy now” (real democracia ya) and “we are people” (somos personas) against hardline Spanish activists who insisted on the emptiness and naiveté of this everyday vocabulary. The conviction that the movement’s formulations would have to be broad enough to allow “everyone to fit” was an operating principle of the Spanish contingent of Occupy.

The Spanish Contingent and the 99%

The transit of these people, practices, and ideas between Spain and the United States in the summer of 2011 generated much of the energy that infused the organizational efforts of the Occupy movement that August and September. Of course, many different strains of protest and political thinking came together in the formation of Occupy Wall Street. The movement owed much to contemporary alter-globalization campaigns in Seattle and Argentina at the turn of the millennium, the pro-democratic protests from the Arab Spring that began to send shock waves throughout the West, and the call for American encampments in the dog days of 2011 from the Canadian culture-jamming magazine Adbusters. In July, the group New Yorkers Against Budget Cuts tested out the idea of a protest encampment in the United States with a small tent cluster called “Bloombergville” outside City Hall.

Even before these North American initiatives, however, the push for what would become the Occupy movement began in New York with a solidarity demonstration with the Spanish 15-M movement in Washington Square Park on May 21st, 2011. Over the following six weeks, a group of Spaniards, many of them longtime New York residents, met weekly in a tapas bar under the name of “Democracia Real Ya – NYC” to discuss the situation in Spain and the possibility that a similar type of movement could be achieved in the United States. Cesar Arenas-Mena and Moreno-Caballud began to attend meetings of the New Yorkers Against Budget Cuts in mid-July, and on July 27th, an informational talk on 15-M was held at the Manhattan bookstore Bluestockings. The key moment of this early phase was a meeting on July 31st at 16 Beaver, an art and activist space in the heart of Wall Street. The meeting, organized by Ayreen Anasta, Rene Gabri, Xavi Acarrin and Moreno-Caballud and called “For General Assemblies in Every Part of the World,” brought together participants from the acampadas in Spain and the Syntagma protests in Greece, as well as Japanese, Palestinian, and American activists. It was at this meeting that the first assembly of the NYCGA (at this point referred to as the People’s General Assembly on the Budget Cuts) was announced for August 2nd.

Over the next several days, Occupy’s most iconic and enduring phrase, “We are the 99%, was molded by a number of participants in the NYCGA. The Spanish contingent was absolutely crucial to this articulation. On August 4th, an email thread on the newly-created “September 17th” Google Group, titled “A SINGLE DEMAND,” was initiated. Willie Osterweil began the “A SINGLE DEMAND” email thread by stressing that the NYCGA demand would have to be broad enough to appeal to everyone: “We don’t want observers, we want participants.” Lorenzo Serna, a Latino member of the Outreach committee (and also a Spanish speaker), responded by saying that perhaps what was needed was not a single demand but a single message, something that could “be easily transferrable from me, to someone else.” Isham Christie then differentiated between a “demand,” “that is directed at the state or economic elites,” and a “message,” “that is directed at the folks we are trying to bring into the movement.” Crucially, the “online consensus” that was reached by the group was that the Occupy Wall Street movement needed to be defined less by what it wanted than by whom it wanted to participate. Moreno-Caballud then suggested that the movement’s identity would be defined by how easily its message was understood, and stressed that both the identity and the message would need to combine the political and the economic. Amin Husain added a populist inflection from the American Constitution, putting forth the slogan: “We, the people, are taking to the streets because the government is not hearing us.” Finally, David Graeber drew from the rhetoric of a May, 2011 article by the economist Joseph Stiglitz on the politics of the “1%,” offering up the phrase that would become synonymous with Occupy: “What about the ‘99% movement.’” Graeber elaborated further:

Both parties govern in the name of the 1% of Americans who have received pretty much all the proceeds of economic growth, who are the only people completely recovered from the 2008 recession, who control the political system, who control almost all financial wealth. So if both parties represent the 1%, we represent the 99% whose lives are essentially left out of the equation.

The next day, Santa Cecilia and Moreno-Caballud printed out a flyer, adding the pronoun “we” to the 99%, thereby giving a “collective identity” to the anyone and everyone that would form part of the movement: “We, the 99% call for an open General Assembly Aug 9th 7:30 PM at the Potato Famine Memorial.” The concept of the 99% began to circulate through the streets of New York. A few weeks later, the activist and blogger known as Chris transformed the slogan into its final form, creating a Tumblr page with the meme “We are the 99%.” These were the words and the concept that Santa-Cecilia and Moreno-Caballud recuperated in their email in September during the first week of the encampment.

Occupy Loves 15-M?

How, then, has the Spanish contingent been virtually effaced from the prehistory of Occupy Wall Street? It strikes me as more than incidental that the group that most worried about and worked toward the inclusivity of the movement has been effectively excluded from the main narratives about Occupy’s origins. Why is this the case? More than anything, I believe it was because the Spanish contingent was more determined than many of the other participants in the NYCGA in carrying the belief in a leaderless movement down to the organic level. Since those who were interviewed in the Spanish acampadas often refused to give more than just their first name, this practice that was initially replicated by the Spanish contingent of Occupy. Especially in the early days of the Zuccotti encampment, this tactic of depersonalization was often met with confusion, hostility, or (more often) indifference by an American society that is heavily invested in the cult of celebrity.

The lack of self-promotion by the Spanish contingent of Occupy meant that their visibility and influence in the movement slowly ebbed. By the time Occupy Wall Street captured the popular imagination in the last weeks of September, the Spaniards no longer had significant input into the main organs of the movement, either in Zuccotti Park or elsewhere. This shift confirmed, in part, the effectiveness of their concept of a movement of the 99%. On the other hand, the fact that they were less visible than other occupiers meant that the global media—and consequently academics and activists, since for all the rhetoric we remain tied to narrow channels of information—essentially ignored the concrete connection between 15-M and Occupy.

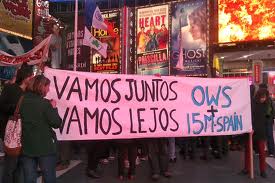

On May 1st, 2012, during a May Day march through the streets of Manhattan, a group of Occupy participants retroactively attempted to bridge the identities of the two movements. Worried that people in both the United States and Spain still saw Occupy as a homegrown movement focused on the American political systems, they carried a sign that said: “Occupy Loves 15-M (Spain).” I have pictures of the Spanish contingent carrying the sign from Union Square down Broadway and all the way to Zuccotti Park, but I’m not sure how many others do. The sign bore witness to a certain kind of defeat. If it was true that many in Occupy “loved” 15-M, it had now become impossible to state the more encompassing truth: that 15-M was, or was a major part of, Occupy Wall Street.

One final word about the history of this article. Over the past five months, I have submitted it to several publications, mainly outside of the Occupy networks so as to reach a broader audience. Up until now, all have declined to publish it. The mind of an editor is notoriously like a black box, yet one question has continued to come up. Why should we print this when Occupy Wall Street is no longer a current event? The concern is understandable for those in the publishing world, who are often pressed by the media logic of presenting information that touches on the here and now. But I wonder if it is the right question for those of us still trying to grapple with what Occupy Wall Street was and what the Occupy movement has become.

When a translated version of the article finally appeared in an online Spanish newspaper two weeks ago, one commenter fumed: “Try telling this to the Yankees and see if they pay attention…this document should help to recognize the Spanish role in the movement, but it won’t, just as others haven’t been able to before.” This is all the more disturbing given that the main strategy that the media used to discredit Occupy Wall Street was to suggest that it had been started by a group of American hipsters and radical activists. How will it be possible to have a conversation about the legacy of Occupy, by almost all accounts the most significant American social movement of the past thirty years, without first acknowledging that its beginnings were vastly different from the origins ascribed to it by journalists, academics, and many within the movement itself? An astonishingly diverse group of voices from around the world went into the articulation of the Occupy message. This is not an argument. It’s a fact. I’ll let you decide if you think people should know about it.