By India Stoughton

In late 2011 four Arab women, inspired by the success of the Arab Spring demonstrations but horrified by the backlash against the women who had protested side-by-side with men in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Syria, decided to start their own Facebook group. They called it “The Uprising of Women in the Arab World.”

Founded by activists Daila Haidar and Yalda Younes from Lebanon, Sally Zohney from Egypt and Farah Barqawi from Palestine, the group calls on men and women from all ethnic, social and religious backgrounds to unite in the face of discrimination “to say no to violence against women, no to their allegiance to men, no to repression and abuse, no to their treatment as second class citizens” and to demand the full application of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights for Arab women as well as men.

Over the past year the women have worked together to construct a wide-reaching and effective virtual uprising, continually evolving new strategies to reach out to like-minded activists regionally and internationally and to create a community of supporters with numbers large enough to ensure real influence.

“The initial aim of the page was to get to the point where we can create synchronized events,” explained Younes, “because the most incredible thing about the Arab Spring is not only the fall of the dictators but it’s this global solidarity created between the citizens, which doesn’t exist at all at a state level. The governments never support each other — the Arab League is a joke.”

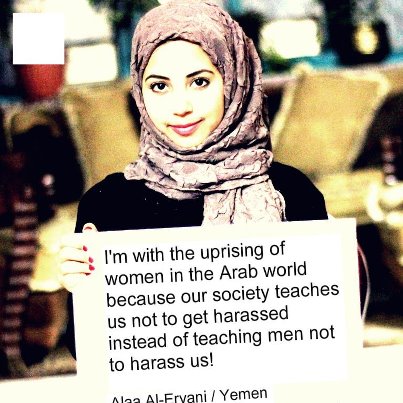

Fifteen months after founding the group, the organizers have reached the point where they are ready to make the virtual uprising physical, thanks to a photo campaign launched last October. The organizers asked members of the group to post photos of themselves holding a sign explaining why they support the women’s uprising. Until that point the page had attracted 20,000 supporters over the course of a year. Within two weeks of the photo campaign’s launch that number had doubled and over the last four months it has continued to steadily rise, with the total number of supporters currently standing at just under 100,000.

Thousands of women from across the Arab world have taken part — the majority of them from Palestine and Saudi Arabia, two societies relatively unchanged by the Arab Spring. Many non-Arabs, as well as men, have sent in messages of support. While the organizers welcomed the support, they were also wary of some non-Arab members of the group who they say did not fully understand the problems facing women in the Middle East and who tried to impose their own cultural and social expectations on them.

“It’s very patronizing,” said Younes. “We don’t want anyone to liberate us.” She added, “We don’t want this projection of the West that it is poor veiled women who are primitive, or a lack of education. Not everything is a lack of education and these campaigns have shown that women are very much aware of their rights.”

The group received international media attention after a Syrian girl named Dana Bakdounis posted a controversial photo of herself with her hair uncovered, holding up her passport to show the photo, in which she wears the veil, and a handwritten sign that read in English and Arabic: “I am with the uprising of women in the Arab world because for 20 years I wasn’t allowed to feel the wind in my hair and my body.” Facebook removed the photograph from the group page and the girl’s own profile after it was reported as “offensive,” and the organizers accused Facebook of censorship after their accounts were suspended. Facebook later told the BBC that it was a misunderstanding, restoring the photo and lifting the ban after a few days.

(Facebook/The uprising of women in the Arab world)

The four women have consistently allowed the needs and suggestions of the group’s supporters to drive the direction of their campaign. When they began receiving stories from women who wanted to share their experiences, they decided to launch a call for true accounts of sexual discrimination and abuse. “We’ve received 65 stories so far for this campaign from all over the Arab world and we’re still receiving stories,” said Farah Barqawi. “Some women even started posing questions at the end of their stories about what they should do.”

The next step, she says, is a campaign to systematically document the laws pertaining to women across the Arab states so that supporters can easily research which laws are already in place to protect them from abuse, which laws are contributing to ongoing sexual inequality, and what more needs to be done to ensure safety and equal rights for women. Though this campaign will start online, the organizers are hoping to manifest it physically by printing out the information and arranging talks at universities and schools across the region.

In the meantime the group is about to undertake its first physical demonstrations, protesting sexual violence against women in Egypt, which has escalated exponentially since the 2011 uprising.

“We were thinking for a long time what the suitable time to go to the street is and it was pretty hard to decide,” said Barqawi. “Just protesting on one day with no real cause, just for the general cause, is not really what we thought of as intifada [uprising, or literally “spilling over”]. But we felt like the media is not really concentrating on what’s happening to Egyptian female protesters.”

Some people have asked why the protest is being held for Egyptian women in particular, when women in Syria and other parts of the Arab world are also struggling with sexual abuse. “If it’s necessary that this global protest becomes a weekly or monthly one it will become a weekly or monthly one, like the Tahrir Friday protests,” Barqawi explained. “The thing about Tahrir is that it became kind of the Kaaba [a Muslim holy site in Mecca] of revolutionaries.”

“People iconize Tahrir,” she continued. “I have a postcard of Tahrir in my room. I want to wake up every day thinking that my country and every country will reach the point that millions of people decide to topple the ruling system. But finding this icon destroying women instead of empowering them — it’s really painful and it deters us from going to the streets. So this is why Egypt: Egypt is umm al-dunya [the world’s mother] in a way.”

She and the other organizers have made plans to protest outside the Egyptian Embassy in Beirut at 6 p.m. on February 12 and have reached out to activists in other countries to organize similar protests in their own cities. Currently demonstrations have been organized in Cairo, where participants are voting on the best location to hold the demonstration, as well as outside the Egyptian embassies in Tunisia, Yemen, Palestine, Morocco, Syria, Jordan, Mauritania, Thailand, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Canada, Australia, New York and Washington, D.C.

The protesters will hold the Egyptian ruling party responsible for not “taking measures to prevent organized thugs attacking, stripping, raping, injuring and killing peaceful protesters” and demand that laws be put in place and be strictly enforced to prevent sexual harassment in all its forms. They also condemn the common perception of sexual abuse in Egypt, which often involves shaming the victim rather than the aggressor.

“We’re doing the exact opposite of what the traditional Egyptian society and other Arab societies tend to do, which is shaming and silencing,” said Younes. “You can’t put pressure on these women anymore, because we are more numerous. They may seem to control the square, but we are the ones who stand strong together.”

The original source of this article can be found on the Waging Nonviolence website here.