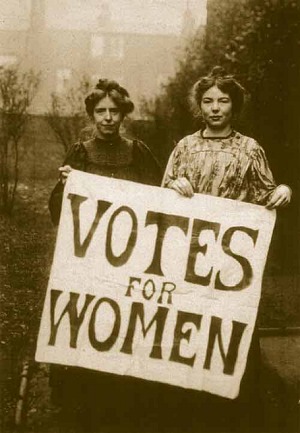

The UK Suffragettes were activists in the British WSPU (Women’s Social and Political Union), led by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, seeking the right to vote for women through some nonviolent methods of protest such as hunger strikes, and other tactics that included pouring destructive chemicals into mailboxes, breaking windows at prestige buildings and night-time arson at unoccupied buildings. Many suffragettes were imprisoned in Holloway Prison in London, and were violently force-fed after going on hunger strike.

The film Suffragette depicts most of such methods, and issues but it seems somehow skewed towards stressing the violence and Emily Davison’s martyrdom (who died under the King’s horse at the Epsom Derby) as decisive for the achievement of the women’s objectives. The longer and nonviolent campaign instituted by leaders other than Emmeline Pankhurst (played in the film by Meryl Streep, who else??!!) is rather absent. For instance no mention is made of the Women’s Freedom League, a breakaway group founded by Teresa Billington-Greig, Charlotte Despard, Elizabeth How-Martyn, and Margaret Nevinson who remained committed to nonviolence following the original ethos of Millicent Fawcett who had started the movement in 1897.

In 1906, Mahatma Gandhi, visiting London, praised the dignified non-violent methods of the English suffragettes, putting their case forward as a moral example to convince his Indian countrymen to adopt the practice of “satyagraha,” or non-violent resistance to the British in South Africa (and later in India).

The new nonviolent group (the Women’s Freedom League generally referred to as “suffragists” to differentiate them from the more violent suffragettes) utilised non-payment of taxes, refusing to complete census forms and organising demonstrations, including members chaining themselves to objects in the Houses of Parliament. They continued their pacifism during World War I, supporting the Women’s Peace Council. On the outbreak of war, they suspended their campaigns and undertook voluntary work, but in 1916 they restarted their lobbying activities, including women’s rights such as equal pay.

There is disagreement as to the effect of the Pankhurst led violence in the campaign. Many support the view that in fact it harmed the cause by depicting women as emotional and irrational. The fact is that the Suffragettes stopped their campaign of violence and supported in every way the government and its war effort during WWI in August 1914. In 1918, the Representation of the People Act was passed by Parliament. Women over 30 years old received the vote if they were either a member or married to a member of the Local Government Register, a property owner, or a graduate voting in a University constituency. Women over 21 received full voting rights in 1928.

The film centres on the life of a working class woman, rather than the middle and upper class ones that formed the majority of the movement at least in its beginnings. Its main strength is to expand the issue beyond voting rights to others such as women’s sexual and work exploitation, lack of rights in relation to their children and domestic violence. The mixed reactions from husbands, employers and the Police add dramatic effect to the interesting depiction of different attitudes and conundrums experienced by the women who become activists.

The final credits include information about when voting rights were achieved in different countries (Switzerland 1971, Saudi Arabia 2015!).

Despite its flaws (may be just my disappointment based on a personal point of view and commitment to nonviolence), this is an inspiring and topical film, and one wonders why it took so long to be made.