For a long time, Algerian identity has been presented through a narrow and selective lens. Many Algerians were taught, directly or indirectly, that their origins were mainly Arab, as if the country’s history began only with the arrival of Arab-speaking populations and Islam. This simplified narrative, repeated for generations, gradually imposed itself as common sense. Yet when history, archaeology, and modern genetics are examined together, they reveal a reality that is far older, deeper, and far more complex.

Research in population genetics consistently shows that the primary foundation of Algerian DNA is indigenous North African, commonly associated with Amazigh populations. This biological continuity has existed on this land for thousands of years, long before the arrival of Arabs, Romans, Ottomans, or Europeans. Today, this ancestral component remains dominant throughout Algeria, including among Arabic-speaking populations. This is not a matter of opinion or ideology, but a fact supported by numerous scientific studies.

Despite this evidence, acknowledging this reality remains difficult for part of Algerian society. This resistance is largely explained by the historical process of Arabization, often portrayed as a natural cultural evolution, when in fact it unfolded in a context of conquest, political domination, and religious transformation. The expansion of Islam was accompanied by the gradual imposition of Arabic as a sacred, administrative, and socially dominant language, marginalizing local languages and identities.

Over time, an ideology took shape that equated Islam with the Arabic language, and the Arabic language with legitimate identity. This confusion produced a powerful but often unspoken dogma: not speaking Arabic, or valuing another language and identity, is perceived as being against Islam. Yet no religion is biologically tied to a language, and Islam has never required the erasure of the peoples who adopted it. This artificial fusion of faith, language, and identity is an ideological construction, not a religious truth.

Today, this Arabist ideology continues to manifest itself in the hostile reactions triggered by any direct reference to Amazigh identity. Many Arabic-speaking Algerians perceive the affirmation of Amazigh roots as a threat, or even as an attack on Islam itself. In some cases, those who openly assert their Amazigh heritage are accused of being “against religion” or treated as enemies. This hostility is not a product of Islam as a faith, but of its instrumentalization for identity and political purposes.

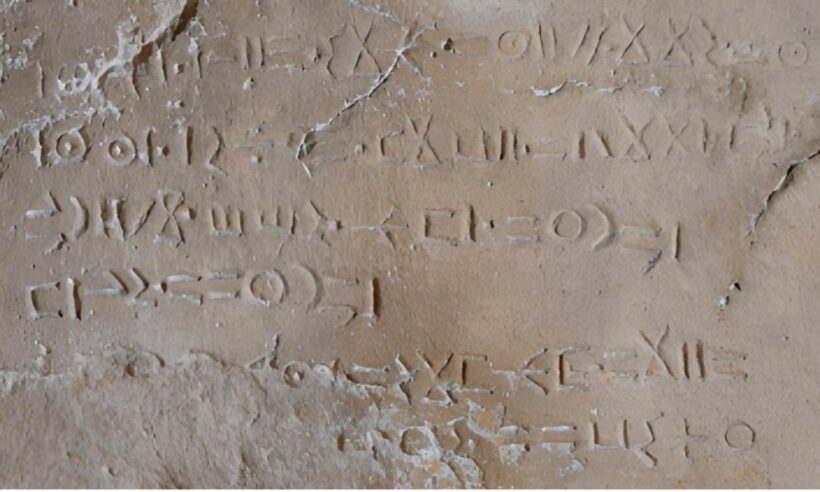

The celebration of Yennayer, the Amazigh New Year, clearly illustrates this ideological drift. Although it is a cultural and ancestral celebration, predating Islam and devoid of any religious dimension, it is sometimes rejected or demonized by certain ideological currents that present it as contrary to Islam. Framing an indigenous cultural tradition as a religious transgression amounts to denying the very existence and historical legitimacy of the Amazigh people on this land.

History, however, is unambiguous. Islam spread in North Africa among Amazigh populations who remained Amazigh in their essence. They adopted a religion, not a foreign origin. Arabization was primarily a linguistic and cultural process, reinforced by political and religious authority, but it never resulted in a massive replacement of populations. Speaking Arabic does not alter DNA, just as embracing a faith does not change a people’s biological origins.

Like all ancient societies, Algeria experienced multiple external influences: Phoenicians, Romans, Vandals, Andalusians, Ottomans, and Sub-Saharan Africans. These contributions enriched the population but never erased the fundamental local continuity. The Amazigh foundation remained the demographic and historical core of the country, integrating external elements without disappearing. It is precisely this continuity that constitutes Algeria’s true singularity.

It is essential to emphasize that Algerian DNA is neither pure nor fixed. Purity is a myth with no scientific basis. Human history is defined by movement, mixture, and exchange. What distinguishes Algeria is not an artificial homogeneity, but the extraordinary depth of human presence on the same land over thousands of years.

Telling the truth about Algerian DNA and about the mechanisms of Arabization is not an attack on Islam or on the Arabic language. It is a rejection of ideological amalgamation and instrumentalization. Recognizing the Amazigh foundation of Algeria takes nothing away from anyone; on the contrary, it allows for the construction of a more honest, calmer, and inclusive national identity.

No nation can build a solid future on the denial of its own history. Understanding the gap between Arabist ideology and the genetic, historical, and cultural reality of Algeria is a necessary step toward reconciliation with our past, with science, and ultimately with ourselves.