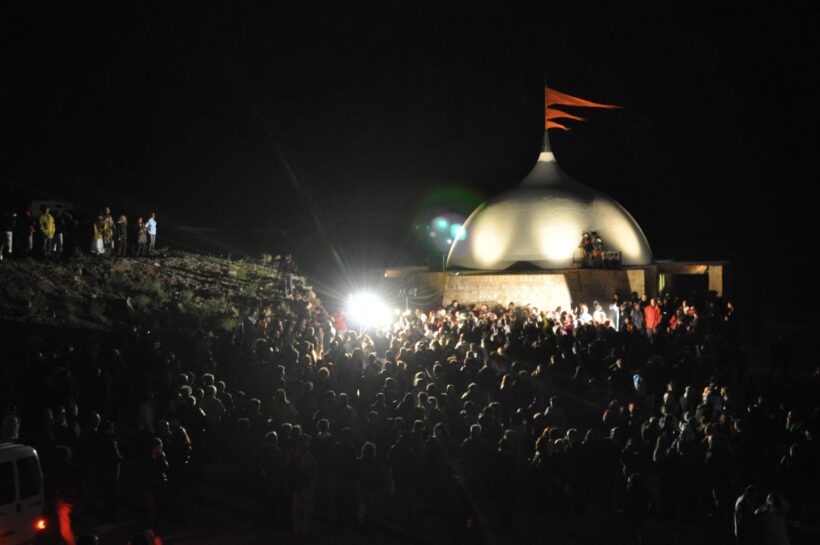

At the Punta de Vacas Study and Reflection Park, a place far from the centers of power but very close to the deep heartbeat of Humanity, Silo—founder of New Humanism—delivered a brief but very meaningful greeting at the beginning of the local calendar year 2010:

“We should celebrate a new year in each cultural calendar, or in a global calendar that must be configured in the future Universal Human Nation.

The intention of that future calendar is unfolding right now under the sign of Peace and Nonviolence.

For now, in all cultures, dates, and languages, we want to celebrate together for that new world which, despite the atrocities of war, injustice, and despair, is already hinted at in the faint breeze of humanity’s dawn.

For ourselves and for all human beings, let us anticipate the embrace of Peace, Strength, and Joy.”

Surrounded by colleagues from a wide variety of cultures, the thinker and spiritual guide subtly alluded to the need to decolonize, in a cultural and religious sense, a calendar established by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582, which gradually replaced the Julian calendar in the West and attempted to impose itself, with the advance of European colonial powers, the calendars of different cultures.

However, the various celebrations remain deeply rooted, showing that beyond the power and violence of external impositions, peoples find inspiration in the diversity of their own cultural memories.

Diwali, for example, is the Hindu New Year, presided over by the goddess Lakshmi, consort of the god Vishnu in that mythology. It is one of the most significant and joyful nights of the year. For their part, Sikhs celebrate on this occasion the liberation of their sixth guru, Hargonbind, and pay homage to the ten spiritual gurus of Sikhism.

The Jewish people celebrate the beginning of their year—Rosh Hashanah—during the first two days of Tishrei, the seventh month of their calendar, commemorating the creation of man, according to the Hebrew worldview.

In China, celebrations begin on the first day of the first lunar month (正月, zhēng yuè) and end on the fifteenth, when the Lantern Festival (元宵节, 元宵節, yuánxiāojié) is celebrated. During this period, the largest human migration on the planet takes place, the “spring movement” (春运, 春運, chūnyùn), and millions of people travel to their places of origin to celebrate the holidays with their families.

In Iran, Central Asia, the Balkans, the Caucasus, the Black Sea basin, the Middle East, and other regions, Nowruz, the Persian New Year, has been celebrated for over 3,000 years, coinciding with the spring equinox.

In Sri Lanka, the date is governed by the Sinhalese astrological calendar and includes food offerings, purification rituals using fire and water, and the preparation of festive meals.

The vast and diverse African continent is home to a unique cultural richness that is reflected in the traditions with which different communities celebrate the end of the year. Each of them is a transformative experience. The rich voodoo culture plays an important role in the continental West, with ceremonies and rituals performed to bid farewell to the old year and welcome the new. Among the Yoruba, the “Odun Ifa” festival celebrates the new year with rites honoring Ifa, the divine oracle. These practices seek to ensure the protection and guidance of ancestral spirits for the coming year.

Ethiopia follows the Julian calendar, and its New Year is known as Enkutatash, while in Ghana, the “Hogbetsotso” is a festival of the Ewe ethnic group that celebrates the New Year with processions, dances, and purification rituals. In several regions of Mali, communities such as the Dogon celebrate the end of the year by lighting symbolic bonfires. This ritual act represents the burning of the old to make way for a new cycle.

Among the Zulus, the Umkhosi Wokweshwama, or “First Fruit Ceremony,” marks the end of one agricultural cycle and the arrival of a new one, while in southern Ivory Coast, the Nzema people celebrate Abissa, a festival that combines music, masks, and social satire. Although it can last for several weeks, the last ceremonies usually coincide with the turn of the year. This period is an opportunity to collectively reflect on the challenges and achievements of the year, in an atmosphere of constructive criticism and reconciliation.

In the Muslim calendar, the new year is on the first day of Muharram (the first month of the Islamic calendar). Much like the Hebrew terms, the new year is called “R’as as-Sana” in Arabic. Many Muslims take advantage of this date to remember the life of the prophet Muhammad and the Hijra, or emigration, he made to the city now known as Medina.

In Russian regions, the Old New Year, often known as “Malenitsa,” is celebrated to mark the end of winter and welcome the arrival of spring. This holiday combines elements of pagan Slavic culture with Christian influences, creating a unique amalgam of traditions that have stood the test of time and fused ancestral beliefs with the Orthodox faith.

In South Korea, families celebrate Seollal on the second new moon after the winter solstice. On this occasion, ancestors are honored and the importance of family and unity in Korean society is highlighted.

The Andean New Year, celebrated in several South American cultures, coincides with the winter solstice and combines ancient knowledge of solar cycles with rituals of gratitude to Pachamama (Mother Earth) and Inti (Sun God). It symbolizes spiritual rebirth and the renewal of vital energy for the Quechua, Aymara, and other Andean ethnic groups.

Thus, as in so many other cultures around the world, people renew their faith in the future, recognizing the long historical journey forged by their ancestors and asking, with their best aspirations, that the new year bring new and better times.