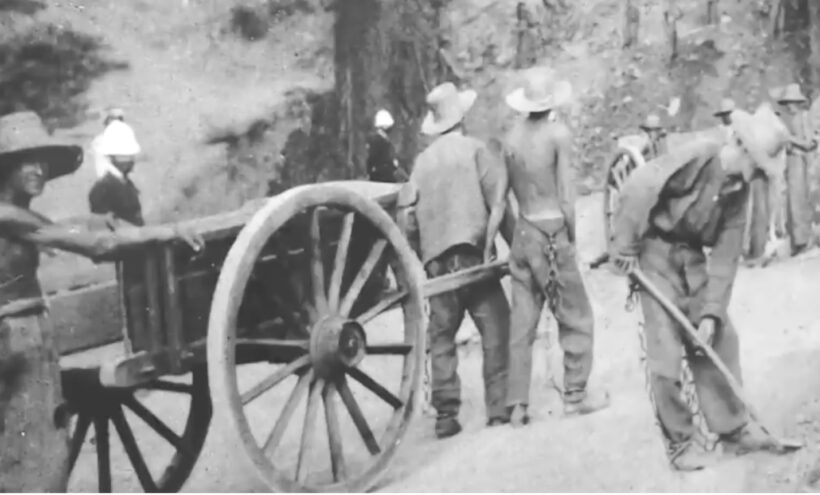

The presence of Kabyles in the Pacific emerges from complex historical processes, encompassing both forced exile and voluntary migration. In the 19th century, French colonial authorities implemented repressive measures to suppress resistance in Algeria, particularly following the 1871 revolt in Kabylia. Many Kabyle insurgents were deported to distant colonies, including New Caledonia and French Guiana. These deportations were intended not only as punishment but also as a means of controlling populations considered politically threatening. Once in exile, Kabyles were subjected to strict regimes of forced labor, constant surveillance, and severe living conditions akin to those experienced by European convicts in penal colonies. The combination of geographic isolation and denial of civil and political rights rendered return to Kabylia virtually impossible, emphasizing the coercive nature of colonial displacement.

Despite these oppressive circumstances, deported Kabyles demonstrated significant forms of cultural and social resilience. Their experiences and identities were preserved primarily through oral transmission, family narratives, and inherited surnames, maintaining a fragmentary yet persistent Kabyle identity. The systematic absence of these histories from colonial and postcolonial narratives has contributed to the relative invisibility of Kabyle trajectories within the historiography of penal colonies, underscoring the marginalization of their experiences in official accounts.

The 20th and 21st centuries witnessed the emergence of a new Kabyle presence in the Pacific, characterized by voluntary migration. This movement was driven by educational opportunities, professional mobility, and familial networks, with New Caledonia remaining a significant destination due to its status as a French territory. Kabyles also settled in Australia and New Zealand, often following prior migration from Europe. Contemporary Kabyle communities in the Pacific are generally small and geographically dispersed, integrating into multicultural urban environments rather than forming formal community structures. This dispersal contributes to their limited visibility within institutional and academic frameworks.

The memory of exile and migration manifests differently across generations. For descendants of 19th-century deportees, recollections are preserved through oral histories and familial accounts, often fragmentary due to the lack of formal recognition. For the contemporary diaspora, identity formation is facilitated through transnational networks and digital communication, resulting in a hybrid Kabyle identity that negotiates between local, national, and global contexts. Collectively, these experiences illustrate a historical continuity between colonial coercion and voluntary migration, highlighting the ongoing challenges of visibility, recognition, and cultural preservation.

Analyzing the Kabyle presence in the Pacific allows for a reconsideration of colonial and postcolonial migration through a transnational lens. These movements reveal the coercive dimensions of French colonialism and its long-term effects on identity and collective memory. Moreover, acknowledging these previously overlooked trajectories raises significant political and commemorative questions, including the possibilities of symbolic reparations and the inclusion of Kabyle experiences within broader national and global narratives.

From the forced exile of the 19th century to the contemporary diaspora, the Kabyle presence in the Pacific exemplifies enduring themes of resilience, adaptation, and identity reconstruction. This history, largely marginalized in mainstream historiography, invites scholars to adopt a decentered and transnational perspective on migration. Restoring visibility to these trajectories is essential for a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between colonial history, migration, and cultural survival.