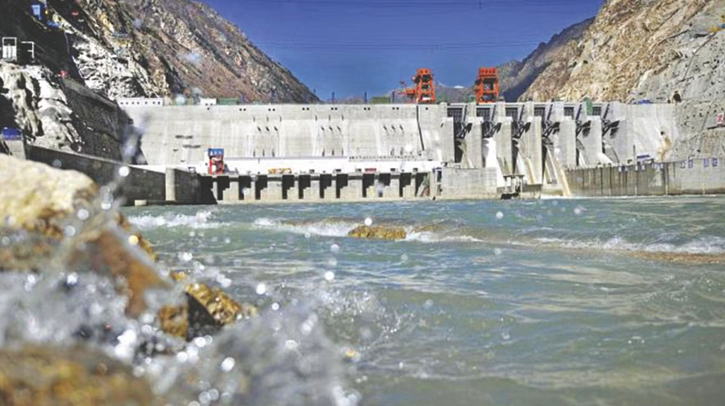

China secretly built the world’s biggest dam over the mighty Brahmaputra River which is likely to jeopardise the ecology, environment, and morphology.

If the mega project goes through will immensely cause hardship for several million people in downstream India and of course Bangladesh.

China’s $1.5 billion dam over Brahmaputra, known as Zangmu Hydropower Station, has raised serious concerns in Bangladesh and India.

China did not consult with the two neighbouring countries, which is mandatory according to the Helsinki Rules on the Uses of the Waters of International Rivers is an international guideline regulating how rivers and their connected ground waters that cross national boundaries may be used, adopted by the International Law Association (ILA) in Helsinki, Finland in 1966.

Dhaka and New Delhi know very well that diplomatic parleys will not dent the simmering issue with the arrogant Beijing administration.

The hydropower dam over the mighty Brahmaputra River, China is opening another flashpoint with India, as Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has its party in power in the northeast state of Assam, where the river flows further south and enters Bangladesh delta.

The Brahmaputra River once it enters Bangladesh, at Bahadurabad in Jamalpur, gets a local name. The Jamuna River directly flows from the yawning Brahmaputra River, said researcher and writer Mohiuddin Ahmad.

The people along the Jamuna River people are critically dependent on the river for rejuvenating life in the monsoon for massive agricultural activities and navigation to millions in the floodplains.

China’s planned super dam on a major river that flows into northeast India threatens to turn into another in a series of flashpoints with New Delhi and Beijing and is likely to spark concerns in Bangladesh.

Brahma Chellaney is professor emeritus of strategic studies at the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi and a former adviser to India’s National Security Council. He is the author of nine books, including ‘Water: Asia’s New Battleground.’

China is unmatched as the world’s hydro hegemony, with more large dams in service than every other country combined. Now it is building the world’s first super dam, close to its heavily militarised frontier with India.

This megaproject, with a planned capacity of 60 gigawatts, would generate three times as much electricity as the Three Gorges Dam, now the world’s largest hydropower plant.

China, though, has given few updates about the project’s status since the National People’s Congress approved it in March 2021.

China presented the super dam project for the approval of the National People’s Congress only after it had built sufficient infrastructure to start transporting heavy equipment, materials, and workers to the remote site.

Barely two months after parliament’s approval nearly three years ago, Beijing announced that it had accomplished the feat of completing a “highway through the world’s deepest canyon.” That highway ends very close to the Indian border.

Opacity about the development of past projects has often served as cover for quiet action. Beijing has a record of keeping work on major dam projects on international rivers under wraps until the activity can no longer be hidden in commercially available satellite imagery.

The super dam is located in some of the world’s most treacherous terrain, in an area long thought impassable. The hydrology and river morphology have not been fully explored, meaning research on the gigantic river is still under study by experts.

Bangladesh is trailing behind in conducting a study on the river Brahmaputra, said Ahmad, who had worked for Bangladesh Delta Plan (BDP) for 100 years.

To understand, the Brahmaputra, known to Tibetans as the Yarlung Tsangpo, drops almost 3,000 meters as it takes a sharp southerly turn from the Himalayas into India, with the world’s highest-altitude major river descending through the globe’s longest and steepest canyon.

Twice as deep as the Grand Canyon in the United States, the Brahmaputra gorge holds Asia’s greatest untapped water reserves while the river’s precipitous fall creates one of the greatest concentrations of river energy on Earth. The combination has acted as a powerful magnet for Chinese dam builders.

During the British Raj, several British expeditions and researchers failed to enter Tibet, now a territory of China, said Sanat Chakraborty, a journalist and researcher on the river morphology, life and history of rivers in northeast India.

Another journalist Samrat Chowdhury, an acclaimed Indian journalist who floated on the Brahmaputra for days in the northeast as well as in Bangladesh has written a book The Braided Rivers, which describes the life of boatmen, fishermen, the chars (shoals) people, vibrant trading in hats (market) and farmers. He described how millions of people are dependent on the river.

The behemoth dam, however, is the world’s riskiest project as it is being built in a seismically active area. This makes it potentially a ticking water bomb for downstream communities in India and Bangladesh, writes Chellaney.

What is alarming, the southeastern part of the Tibetan Plateau is earthquake-prone because it sits on the geological fault line where the Indian and Eurasian plates collide.

The 2008 Sichuan earthquake, along the Tibetan Plateau’s eastern rim, killed 87,000 people and drew international attention to the phenomenon of reservoir-triggered pressure from a dam’s reservoir may have helped trigger the earthquake.

Some Chinese and American scientists drew a link between the quake and Sichuan’s Zipingpu Dam, which came into service two years earlier near a seismic fault. They suggested that the weight of the several hundred million cubic meters of water impounded in the dam’s reservoir could have triggered RTS or severe tectonic stresses.

But even without a quake, the new super dam could be a threat to downriver communities if torrential monsoon rains trigger flash floods in the Great Bend of the Brahmaputra. Barely a few years ago, some 400 million Chinese were put at risk after record flooding endangered the Three Gorges Dam.

In pursuing its controversial megaproject on the Brahmaputra, China is cloaking its construction activity to mute international reaction, alleges the Centre for Policy Research.

The Brahmaputra was one of the world’s last undammed rivers until China began constructing a series of midsized dams on sections upstream from the famous canyon. With its dam building now moving close to border areas, China will in due course be able to leverage transboundary flows in its relations with rival India.

But the brunt of the environmental havoc that the megaproject is likely to wreak will be borne by Bangladesh, in the last stretch of the river. The environmental damage, however, is likely to extend up through Tibet, one of the world’s most bio-diverse regions. In fact, with its super dam, China will be desecrating the canyon region which is a crucial Tibetan holy place.

A cardinal principle of water peace is transparency. The far-reaching strategic, environmental and inter-riparian implications of the largest dam ever conceived make it imperative that China be transparent. Only sustained international pressure can force Beijing to drop the veil of secrecy surrounding its project.