Based on the work collected in the cartography “Bogotá, city of memory”, the exhibition “I resist, therefore I am” offers an overview of the struggles and resistance of the last eighty years of Colombia’s history.

Published: El Mundo Obrero

The exhibition is a living exhibition because its content will change over time to cover “all the events and processes of the project”, in the words of José Antequera, director of the Centre for Memory, Peace and Reconciliation (CMPR) in Bogotá, where it is installed and whose inauguration took place on 24 March 2023.

The map of resistance in Bogotá that gives rise to this exhibition contains 91 points of memory of events that violated civil liberties and rights, and of the victims who have been left behind, the aim of which is to collaborate in the construction of new memories and new citizenships to fight against silence and oblivion.

The exhibition is a must-see, both from a historical and pedagogical point of view, to get to know and see all the life and death sown in the Colombian territories, together with all the struggles, hopes and resistances that have allowed their people to survive and continue to hold on to their lands and their existence.

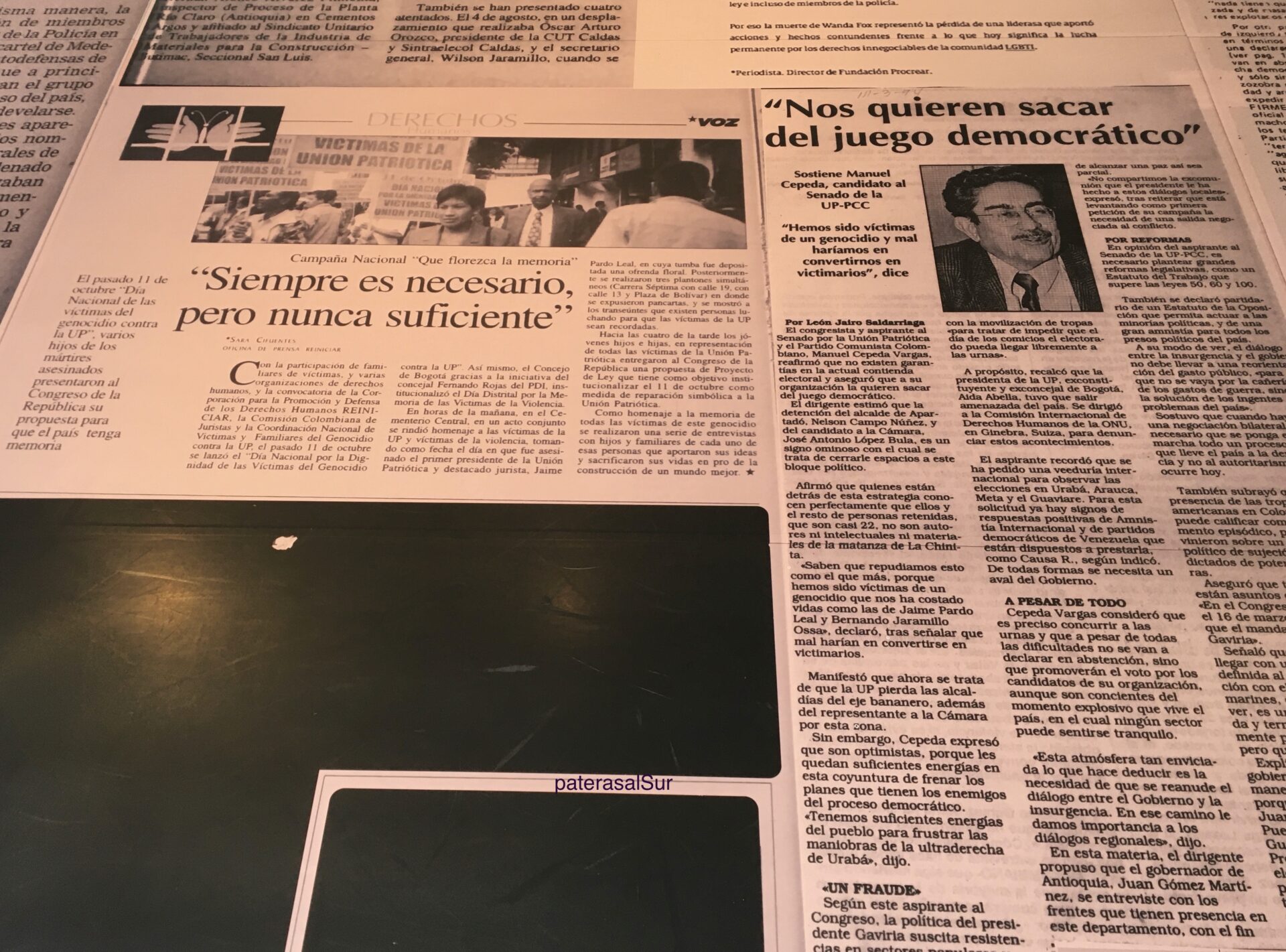

The entrance opens with the media as the main protagonists, with sheets of paper spread out on the floor that reproduce news about outstanding events in recent history and with some spaces in black as a call for attention to that media censorship that ignores or does not report anything that could directly affect the interests of the corporations that finance them or the powers that govern them.

Reproduction of news items from the period covered by the exhibition. Photo by Iñaki Chaves.

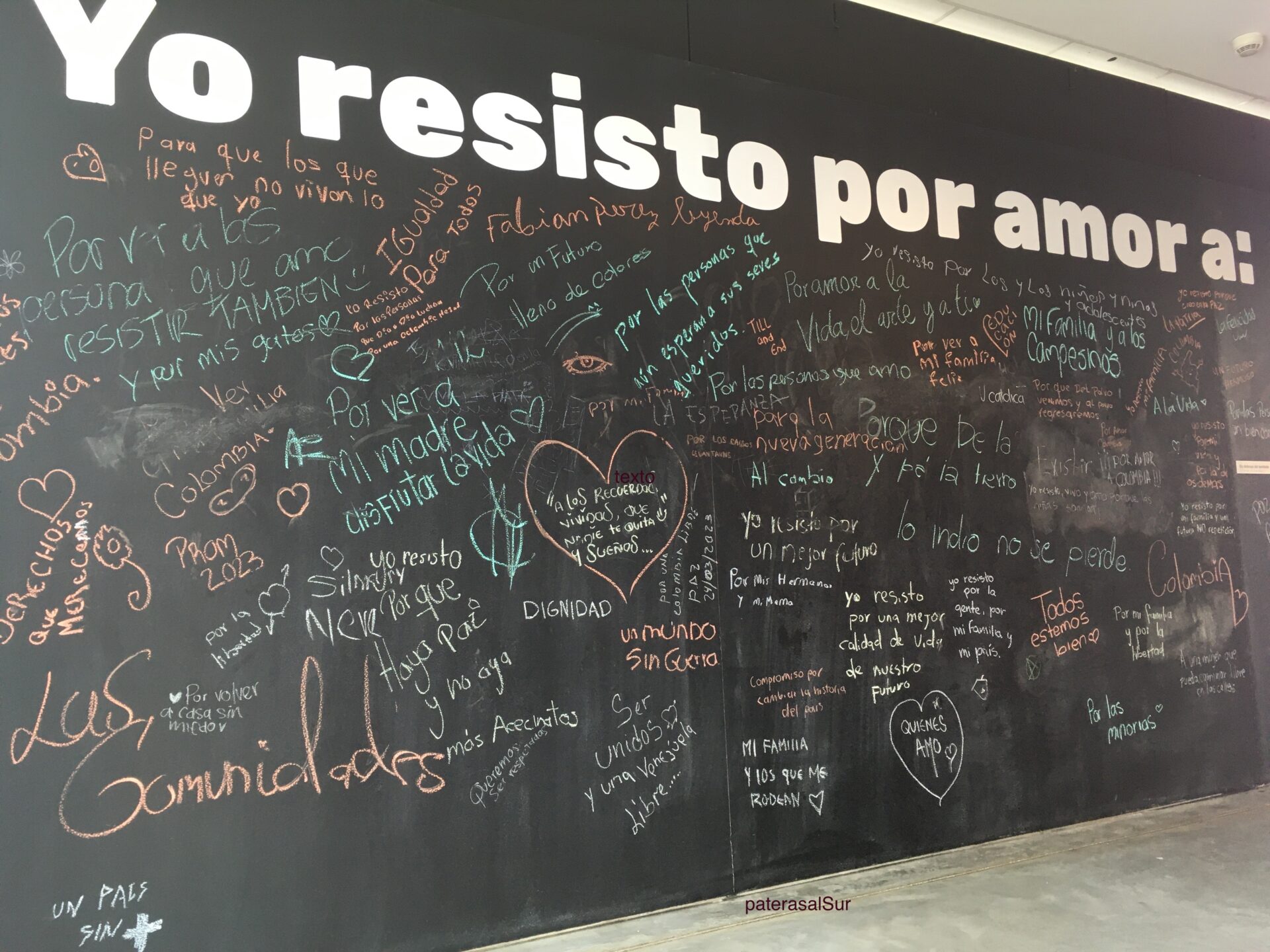

Organised as a labyrinthine journey through violence and resistance, which is nothing else but a resistant labyrinth in the history of Colombia, the room offers ten stages that begin with the question, “What is memorable? “which include “Voices of the present”, “For peace and democracy”, “I resist, therefore I am” (from the victims whose resistance deserves to be valued and heard), “In defence of territory”, “I resist for the love of…”, “The exoduses that build us”, “Vestiges”, “Common cause” and “Bogotá, city of memory”, leaving open a hopeful exit towards peace.

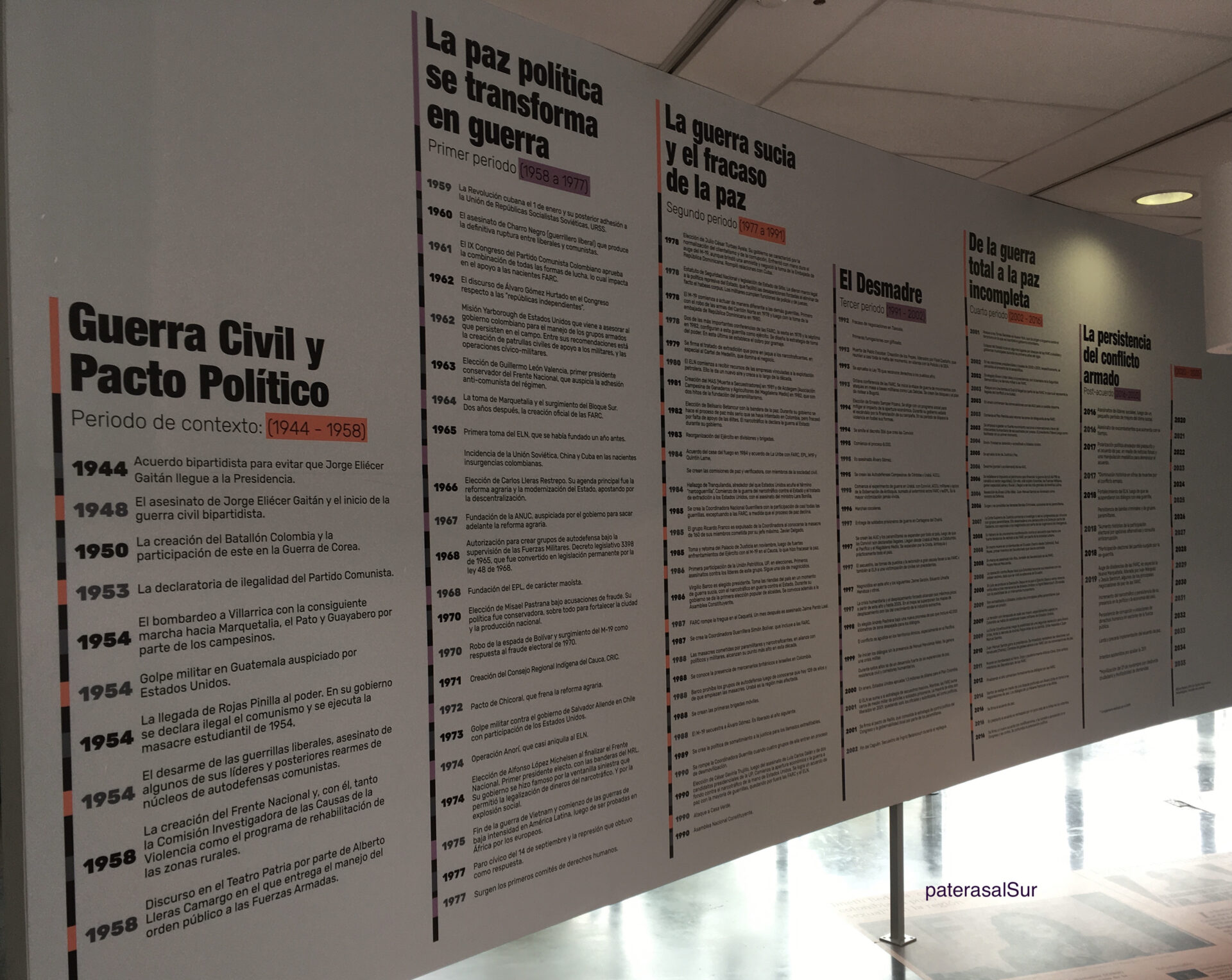

One panel contains the timeline, drawn up by sociologist and journalist Alfredo Molano and included as part of his contributions to the work he carried out as a member of the Truth Commission, with six periods from 1944 to 2019 (the year of his death), with some notes added by the CMPR itself, and a stage to be written from 2020 to 2035 that will hopefully be recorded only in ink and not in blood. Curiously, the chronogram does not include the year 1991 in which the current Political Constitution of Colombia was approved.

With this exhibition, the Centro de Memoria does not intend, in the words of its director, “to tell a final story about what happened in the conflict, but rather it is an exhibition that has been constructed so that everything can be discussed”. The idea is not to look at history in a static way, but rather for “there to be a public conversation” about everything that is exhibited in it.

Colombia, a country that exists because it resists, has in this exhibition a nod, as explicit as it is symbolic, to the need to remember its victims and its social struggles, its dreams of democracy and peace. A memory that is a “map to be built”, indispensable to be able to build a future of dignified life.

As 9 April approaches, the 75th anniversary of the assassination of the liberal political leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán and a new National Day of Memory and Solidarity with the Victims of the Armed Conflict, it is essential to visit the exhibition “Resisto, luego existo” (I resist, therefore I am) to understand the history of this country, its realities and the desires of its citizens to build a new Colombia from all the narratives that constitute it, from all its memories.

Timeline of the eighty years of history covered by the exhibition. Photo: Iñaki Chaves.

Timeline of the eighty years of history covered by the exhibition. Photo: Iñaki Chaves. Reasons to resist and exist. Photo: Iñaki Chaves

Reasons to resist and exist. Photo: Iñaki Chaves Places of memory in Bogotá. Photo: Iñaki Chaves

Places of memory in Bogotá. Photo: Iñaki Chaves