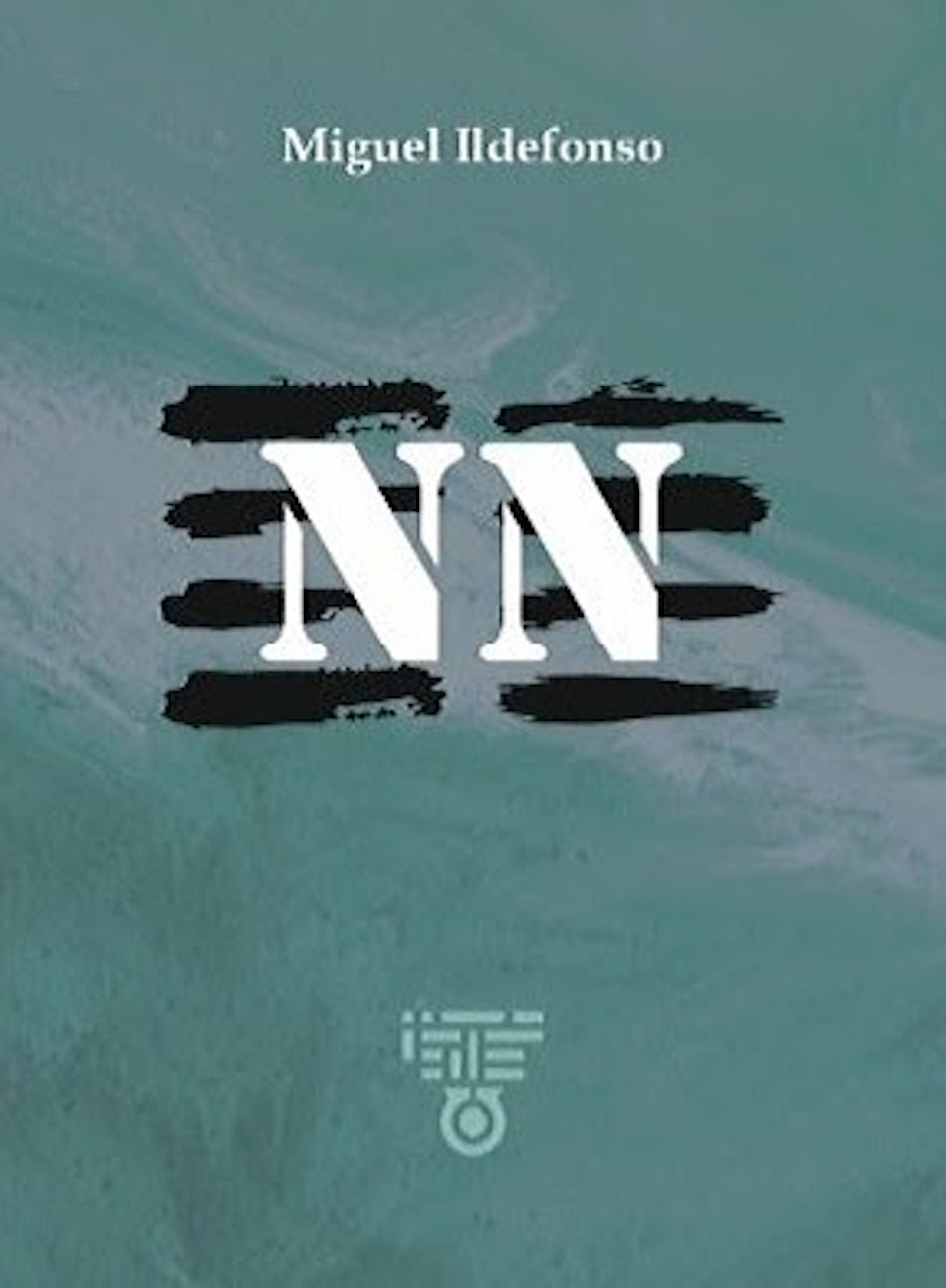

The great Peruvian poet Miguel Ildefonso presented his book “NN” at the International Book and Arts Fair of La Molina, where he was also awarded a prize by the Municipality of that district for his long and prolific creative career.

By Sol Pozzi-Escot

You were honoured for your career during the International Book and Arts Fair of La Molina. What does it mean to you to receive this recognition in the district where you live?

It is an honour. It is more than 30 years of literary work. It is a solitary task that involves a lot of reading, hours a day of writing, a lot of discipline and meditation and endurance. But, unlike a sportsman or a musician, for whom immediate contact with the public is important, the writer and the poet give themselves to the public through the book, it is an intimate approach. Fortunately, and to be in line with the current market, there is already a Book Fair in La Molina, which is the place where the producers of books approach the public, and vice versa. I have just presented NN, a thick book of short stories and tales that is very much about La Molina. I’ve lived there since 2006 and now, finally, in my latest books, I’ve been able to poeticise it. For this reason, and because I am a good neighbour, I was happy to receive this high recognition.

From the formation of Neón to the present day, how would you say your themes of interest for poetic creation have changed and evolved?

I began to write, to create, to make books, to fly, from about 1987. In those early days I explored different styles, while at the same time I was interested in studying in depth the poetics that could help me to express what I needed to express. With some friends from various universities and neighbourhoods, we formed the group Neón in 1990. It was a generational, multidisciplinary, countercultural movement. We were united by the urban vibe, the style that came from the tradition of Baudelaire, Rimbaud, the beatniks, Hora Zero, neo-indigenism, the underground scene in the centre of Lima, Kloaca. Over the years, and not just me, or the ex-members of Neón, but all my class of the nineties, we have shown that we have been developing and evolving towards more personal or original aesthetics. It was our turn to appear at a time of important changes in history. Not rhetorical changes, but real, scientific ones. That’s why poetics today is linked to the development of knowledge. Not so that an artificial intelligence can write poetry. But precisely so that the human remains human, with a “soul”.

In an interview, you said, “For 20 years I have been writing only one work, already finished”. How would you define the common thread of your poetic work?

A figure who opened up a cosmos of creativity for me to apply to writing in a dramatic and festive country like Peru, a multicultural country, was the Puno painter Victor Humareda. His eclecticism, his humour, his critical vision, his search for beauty, his love of freedom, etc., was inspiring; besides, he lived in La Victoria like me. I knew his habitat as a child, there in La Parada, where he rejoiced in the intense colours of the second-hand clothes sold in Tacora. My first book, Vestigios, which will be 25 years old in 2024, begins with a poem dedicated to him. Then I travelled a lot, like Jack Kerouac or Matsuo Basho. I have lived in the United States for two seasons. Between the first and the second I left Apolo, in La Victoria, and moved to La Molina. The thread is the voice of this transhumant, son of migrants, who observes his neighbourhoods, his hills, his apus, and the cities, the deserts, the beaches, the mountain ranges, the jungles, the rivers, the skies, the crepuscules, and he asks himself questions, and seeks responses in writing, in scientific and sentimental observation, in meditation and in reading. I talk to Víctor Humareda in La Molina.

Does poetry help to preserve the human character of people and societies?

Poetry is the manifestation of that human character; it is something made of spirit which, converted into language, has become not a thing, but the living testimony of the good part of what is human. A central theme in all my literary production is that of Peruvian identity, my identity, and I continue beyond that, in the debate about what is human or why I am here or what I am here for. When I was a child, my mother used to tell me about her experiences as a child in the highlands; she let me let my imagination run wild. When she passed away, it was not until later that I was able to get to know that village at an altitude of more than three thousand metres in the central Andes, beautiful, between mountains full of crops and eucalyptus trees. The same happened with my father; when I got to know the estancia where he grew up, I wanted to write about the family memory. What they lived through is almost gone, the people are gone. But I believe in words, in writing and its power. That is why I live.