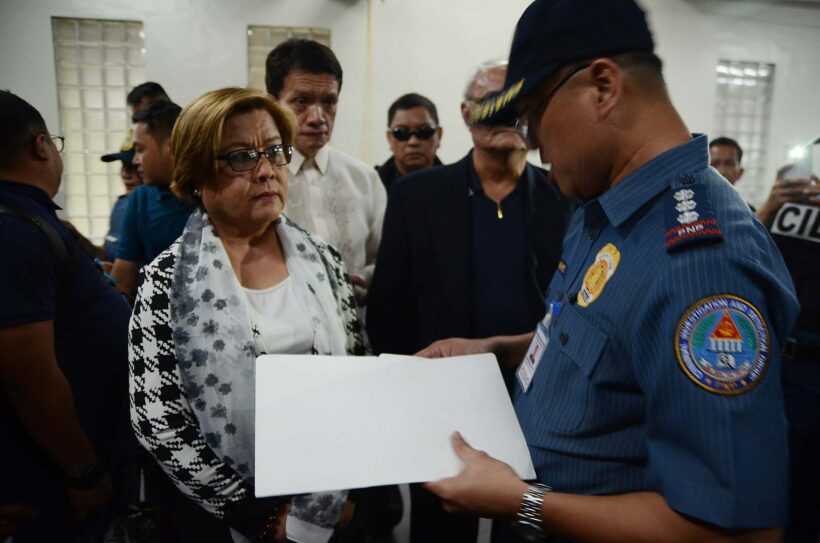

Pressenza journalist Perfecto Caparas interviewed political prisoner Leila M. de Lima, former senator, justice secretary, and chairperson of the Commission on Human Rights. On October 9, 2022, de Lima was taken hostage by a fellow prisoner inside her cell where former president Rodrigo Duterte’s government locked her up on February 24, 2017 on trumped-up drug charges. This is the second part of the interview.

Civil society

Perfecto Caparas (PC): Did you feel supported by the government when you launched your investigation as CHR chairperson into the summary executions in Davao?

Leila de Lima (LDL): If you will recall, the government at the time, headed by then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, did not have the best track record for human rights. In fact, the Davao Death Squad first came to national and even international prominence due to the report released by then Special Rapporteur Philip Alston, who was sent to the Philippines because of the disturbing trends of summary or extrajudicial killings that even the international community was taking notice of.

So when I was appointed as Chairperson of the Commission on Human Rights, I knew that I might not necessarily receive the support of the government. The best I could hope for is that the CHR be given a free hand to investigate and take necessary actions within the parameters of its mandate. And that is pretty much what happened, i.e., I mostly felt that the government gave neither support nor any outward hostility to our investigation, likely because the Administration was well aware that it was facing sanctions if it could not show improvements in the handling of cases of human rights abuses.

PC: How about later when you were the chairperson of the Senate Committee on Justice and Human Rights who initiated and led the senate investigation into the “drug war” killings?

LDL: That was, truly, a totally different experience altogether. One that I did not realize the full impact of until years later.

At the time, I truly believed that common decency and the spirit of public service would move more of my colleagues in the Senate to support the investigation.

At first, I thought that most of them were waiting to see how the investigation would progress, that once evidence has been presented, they would do the right thing.

Perhaps it’s a reflection of my own good faith that I did not expect some of my own colleagues to prematurely put an end to the investigation after ousting me as Chairperson of the Committee on Justice and Human Rights. Sure, I understood enough that, by connecting the extrajudicial killings in 2016 to the modus operandi of the Davao Death Squad through the testimonies of Edgar Matobato and Arturo Lascañas, I was risking my Chairmanship. But, at the very least, I expected my colleagues to continue the investigation in good faith and in earnest and see it to its logical end. That they did not even allow the witnesses under the protection of the CHR to testify, including those who were eyewitnesses to some of the killings, is still a move that I could not comprehend to the point of being enraged. Of course, without hearing out those witnesses, they would say that there is no evidence that the killings are state-sponsored – not because the evidence did not exist, but because they refused to hear and consider it.

PC: How about civil society, what was their response? Did they support you?

LDL: I think civil society organizations were perhaps my strongest, most vocal and most resilient allies in the fight against the spate of extrajudicial killings linked to the War on Drugs. I think it was because many of them still remember or even had origins from the abuses that happened during the Martial Law Regime of former President Ferdinand E. Marcos, that is why they were not taking a “wait and see” attitude. They knew enough that abuses like those are just precursors to bigger and more enduring Rule of Law and Justice problems. So they understood that it was not something to tolerate in the short run in the hopes that it would run its course in a few days, weeks or months.

Their response was immediate, and it was clear. For that I am grateful because, when I began to experience reprisals, some, if not all of them, also championed my innocence, knowing that I was experiencing persecution due to my work as a defender of human rights.

PC: How about the people at large?

LDL: I think the people at large, meaning the ordinary citizens, were understandably afraid to speak out and make their dissatisfaction known. Surveys at the time were really very telling. While the results would indicate that people tend to support the War on Drugs, it simultaneously showed that people were afraid that they would become victims of mistaken identity or be falsely accused or, worse, killed. It shows that the people did think that “innocent” people are being killed and they fear becoming part of the statistics, which leaves no doubt as to why they tend to say they “support” the War on Drugs – they are afraid.

Do I think that they did not support the killings of innocent civilians? Yes, I am certain that they would have objected more vocally if they were not so afraid of angering the wrong people under a prevailing culture of fear and impunity.

PC: Is there anything that these sectors could have possibly done better during those CHR and Senate investigations?

LDL: I think we could have all used more unity. If the officials in the government who were supposed to serve as the check and balance against abuses by the Executive Department, along with members of the private sector, all saw the problem as a common problem – instead of just the problem of the poor people, who tend to make up the majority of the demographics of the victims – then everyone would have been more alarmed and would have acted with greater urgency against the threat to our society and democracy.

The problem is that everyone was manipulated into thinking that they were on opposing sides: DDS v. Dilawans. Because of how divisive the Duterte government acted (i.e., vilifying those who don’t sing the praises of the President, or who question some of his extremely questionable statements and actions, or even the wisdom of some of his decisions), people were groomed to think that supporting one political side means that those on the other are the enemy. That made the spread of fake news and disinformation so much easier. With that, it was easier to keep the people subservient and afraid.

LEILA M. DE LIMA

21 Oct. 2022