When it comes to pointing out the winners and losers of the recent elections to renew the board of directors of the Constitutional Convention, it is concluded that those who won are only those who obtained the presidency and vice-presidencies of this entity, which will remain in office for the six months that remain for the 155 constitutionalists to arrive at a proposal for a new Magna Carta.

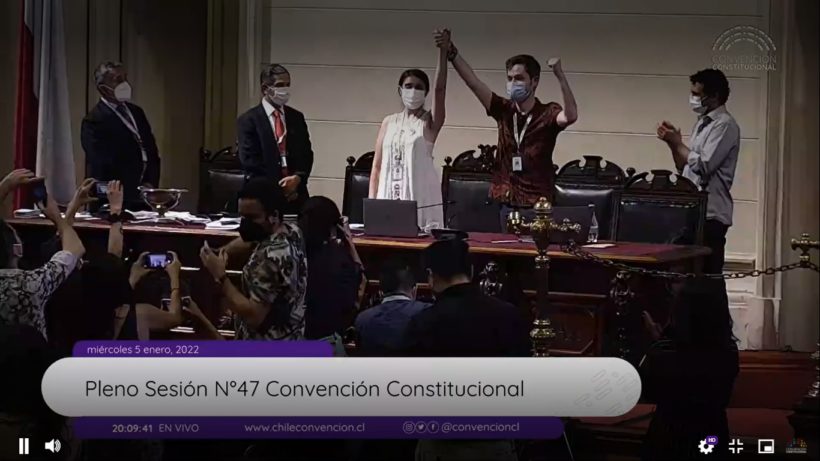

In a spectacle that for many was embarrassing, or more typical of what the political class usually offers us, during two long and tedious days, ten ballots were held to elect María Elisa Quinteros and Germán Domínguez, after at least ten or fifteen names were discarded that did not reach the number of 78 votes required by the Regulations to nominate its top executives. Two names that were not, of course, among the initial favourites and that ended up being imposed by the reciprocal vetoes that were manifested among the political and social groupings of the left. That is to say, those who, as we know, constitute a large majority, which would not be far short of a two-thirds majority of the Convention’s members when they were elected by referendum.

All the parties, apart from the right-wing ones, were forced to elect two members from the so-called social world and from positions that are possibly more radical and, of course, freer than those represented by the political collectives, representatives who seem to be more concerned with securing quotas of power within the Constitutional Convention than with providing ideological guidelines in the definition of our next Magna Carta.

The Frente Amplio of the elected president Gabriel Boric, as well as the communists who constitute the main conglomerate of what will be his next government, did not run together in the negotiations to elect the main heads of the Convention. Even less weight was given to the representatives of the Christian Democratic Party, the PPD, the Radical Party and the Socialists who hope to be included in one of the “concentric circles” designed to house all those who aspire to government posts. Although they do not recognise it, the centre-left parties are without significant strength within the Constituent Assembly. This was demonstrated in the maelstrom of voting and scrutinies, when a PS militant who had managed to attract the will to become president of this entity was discourteously and promptly dismissed simply because of a press report that accused her of having pending problems with the Comptroller General of the Republic, given her alleged fraudulent administration during her term as mayor.

It is important to highlight the fact that María Elisa Quinteros obtained the right number of votes to be elected thanks to the support of an independent from the Right, as well as the noble and generous decision of the lawyer Roberto Celedónal to vote for her and not for himself as all the competitors in this marathon of ambitions had been doing.

Given their precariousness in terms of the number of constitutionalists, the parties supporting the terminal government of Sebastián Piñera and the presidential candidacy of José Antonio Kast, only had to take the stage in this spectacle of divisions and desertions of leftism. Although they were pleased with the enormous difficulty that their contenders might have in agreeing on each constitutional precept. “If they are unable to agree on their leaders, they said, even less will they be able to achieve two-thirds support to approve each article of the Constitution… “which would then have to be endorsed in a national referendum.

Although it transpired that some emissaries of the President-Elect were present at the Convention to instruct his motley first circle of supporters, it could be seen how those of the Frente Amplio ignored the agreement to support the eventual President, backing Beatriz Sánchez, their former presidential candidate, for the post, and this time with a meagre result. Without calculating that those two votes already mentioned above, and which no one counted in their previous calculations, would serve to anoint those who, it is estimated, will not be easily digested by the new Executive or by the entire Chilean party spectrum to be installed or “repeat the dish” in the new Parliament.

A scrutiny that for many may be healthy for the independence that Chileans demand with respect to the decisions of their Constituent. However, the communists were seen as one of the winners of this election day, only for having contributed with their votes to the election of those elected to the leadership of the Convention, distancing themselves from the failed game of their partners in the Frente Amplio, as well as for having denied support to the Socialist Party which they consider too “renewed” and even neo-liberal.

What annoyed many was the expression of so many personal vanities among the members of the Convention, beyond the legitimate right to impose their own supporters in the leadership positions, playing such an important role in defining our new institutional order. There is no doubt that in these two days we are commenting on there were fatal and even obscene negotiations in the greed shown to obtain positions, with very few constitutionalists who did not lend themselves to putting their names “in front of the oxen”.

What there is no doubt about is the total lack of influence of the current Moneda within the constituent body. In addition, the political skill (“wrist”, as they say) of the team that will later arrive at the Executive, which is currently engaged in such a difficult task as nominating ministers, undersecretaries, ambassadors and so many other coveted positions of the President of the Republic’s trust, is also in doubt. Trying to satisfy all those who are on the bandwagon of victory or who insist on getting on or getting close to it.

To all of the above, it should be added that this election day also revealed the rift that exists between those who occupy the seats reserved for the representatives of the native peoples. It is clear that a division was expressed in at least two groups or factions that have a different vision regarding what should be enshrined in the letter of the new Constitution, but also regarding the ratification of what is approved by means of a consultation with the native peoples themselves. The disagreements between the two sectors even raise fears that the new board could be challenged for the procedures used to impose some of their names to the detriment of others. This dispute, if it escalates, could affect the quorums needed to approve the constitutional text by a two-thirds vote. The main trap imposed on the constituent process by the National Congress with the complacency of some left-wing parliamentarians who are now part of the new Executive.