Amid Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s condemnation of the International Criminal Court’s investigation into cases of crimes against humanity involving the murder of 12,000 to 30,000 civilians, at least two major scenarios emerge.

First is the institutional empowerment of the victims of Duterte’s so-called “war on drugs.” This is in terms of their active recognition by the ICC and their official participation in the ICC proceedings. According to Rule 85 of the ICC Rules of Procedure and Evidence, victims “means natural persons who have suffered harm as a result of the commission of any crime within the jurisdiction of the Court.”

Second is the political, moral, and legal significance of the ICC investigation which carries immediate, medium-term, and long-term implications to the hitherto unabated martial law practice by the police and the military of summarily executing suspected criminals and political activists, along with human rights lawyers, and other environmental and human rights defenders.

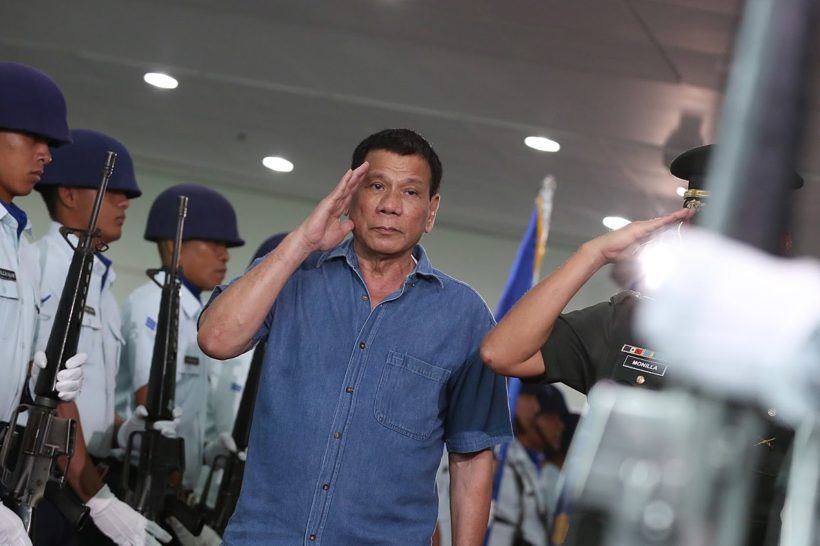

It was at the height of Duterte’s popularity, shortly after winning the presidency on 9 May 2016, that the mindset justifying summary executions gained the upper hand and dominated the national political narrative.

Duterte’s kill orders blasted into smithereens the principle of the rule of law, democratic rights and processes, human rights, and accountability. It is for this reason that the ICC probe carries long-term political and moral significance that goes far beyond the mere criminal investigation and prosecution of Duterte and his top lieutenants who executed his state policy to kill thousands of civilians.

The ICC investigation challenges the police and military mindset – shared and supported to some extent by some segments of the civilian population – justifying arbitrary and summary executions as a means of dealing with criminality. The dark twin of this criminal mindset is the assassination of political activists and human rights lawyers, as well as other environmental and human rights defenders, whom security forces subject to red-baiting by lumping them together with Maoist insurgents.

On 15 September 2021, Judge Péter Kovács, presiding judge, Judge Reine Adélaïde Sophie Alapini-Gansou, and Judge María del Socorro Flores Liera, of ICC Pre-Trial Chamber I, authorized ICC Chief Prosecutor Karim Khan to conduct a preliminary investigation into the situation in the Philippines involving the widespread and systematic killing of civilians from 1 November 2011 – when the Rome Statute of the ICC came into force in the country – up to 16 March 2019, the last day the Rome Statute remained effective a year after Duterte withdrew from the treaty on 17 March 2018.

According to the then ICC Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, in her request for authorization of an investigation pursuant to article 15(3), dated 24 May 2021, Duterte’s security forces and their “force multipliers” killed 12,000 to 30,000 civilians, from 1 July 2016 to 16 March 2019.

Duterte’s withdrawal from the Rome Statute came on the heels of Bensouda’s announcement on 8 February 2018, when she announced that she was opening a preliminary examination of the grisly killings in the Philippines.

The Duterte government has tried to attack the ICC by falsely claiming that the court lacks jurisdiction and that the Rome Statute of the ICC never became effective in the country. This is notwithstanding the Philippines’ official ratification of the treaty and subsequent deposit with the UN Secretary General on 30 August 2011 of its instrument of ratification.

The ICC will certainly take care of Duterte and his apologists who may eventually be found liable for committing offenses against the administration of justice, under Article 70 of the Rome Statute of the ICC, for undermining and jeopardizing the ICC investigation into the mass atrocities in the Philippines.

Victim Empowerment

The Rome Statute of the ICC accords victims the right to participate in ICC proceedings. Once the ICC Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) requests for a preliminary investigation, Article 15(3) of the Rome Statute provides that: “Victims may make representations to the Pre-Trial Chamber, in accordance with the Rules of Procedure and Evidence.” Pursuant to this provision, the OTP notified the victims of crimes against humanity of its request for authorization to investigate the situation.

In its 15 September 2021 decision authorizing Khan to proceed with the preliminary investigation, the chamber wrote: “The Chamber wishes to express its appreciation of the fact that many individuals have come forward with representations to the Chamber on behalf of themselves or on behalf of other victims in the situation.” The chamber noted that, per the ICC Registry’s assessment, “representations were made on behalf of victims including 1,530 individual victims and 1,050 families.”

The chamber’s remarks show the workings of the Rome Statute of the ICC provisions, particularly Articles 19(3), 43(6), 57(c), 64(6)(e), 68(1), and 75, which ensure victim protection, participation, and reparations. Rules 90 (Legal representatives of victims) to Rule 93 (Views of victims or their legal representatives) of the ICC Rules of Procedure and Evidence accord victims their own official representation. Aside from the Office of the Prosecution, and the defense, the victims themselves have their own respective legal counsels who represent their own interests in the proceedings.

The empowerment of victims accorded by the Rome Statute of the ICC assumes heightened significance in the Philippine context in view of the sociopathic manner with which Duterte publicly exhorted the police, military, and civilian population to kill alleged drug addicts, drug peddlers, and criminal elements immediately after he was proclaimed winner of the 9 May 2016 presidential elections.

This victim empowerment that the ICC institutionalizes as an indispensable tool to dismantling impunity serves as a critical counter-force to the Philippine political elite’s insensitive trifling with the lives of the powerless and the poor, whom Duterte’s “drug war” targeted for summary execution.

Moral, Legal and Political Significance

In terms of the moral, political, and legal significance of the ICC investigation, what becomes evident is the further erosion of Duterte’s moral, legal, and political authority to lead. The ICC probe thrusts him into political isolation.

The ICC investigation and the prospects of Duterte facing arrest for crimes against humanity serves as a counter-narrative to Duterte’s kill orders and state policy of perpetrating the systematic and organized murder of civilians on a large scale, even during the pandemic. It is in the moral, political, and legal spheres that the ICC investigation assumes immediate, medium-term, and long-term significance.

Expectedly, Duterte and his political ilk will cover up and protect Duterte from any impending arrest on orders of the ICC for Duterte to face trial before the world’s first-ever independent, permanent, and global criminal court. The political elite will incessantly try to sweep under the rug the grisly murder of civilians, including children, that Duterte allegedly initiated as state policy while he was mayor of Davao City and which he later adopted and operationalized nationwide right after he won the presidency.

Politically, the victims of Duterte’s bloodlust do not owe anything to the elitist, parochial, and anti-poor nature of Philippine politics. It is in this context that the ICC’s empowerment of victims – by according them participatory roles in the conduct of the proceedings – assumes critical importance. It is through the criminal proceedings’ recognition of their official role in the investigation, prosecution, and trial of Duterte and other suspected enemies of humanity that the victims will be able to cast a spotlight on their very own existence, and perforce, the legitimacy and justness of their claims for justice and accountability.

This ICC recognition accords them a powerful voice. This is the only weapon that they can realistically muster in the face of the political elite’s continuing blindsiding of their woes.

Challenges to Cross-Fertilizing ICC Victim Empowerment

Although the ICC institutionalizes victim participation in the investigation, prosecution, and trial of suspected enemies of humanity, much remains to be done in order for their empowerment to actually seep through and permeate the socio-cultural, moral, and political fiber of Philippine society.

Civil society organizations and media organizations have a strategic role to play in popularizing the mandate of the ICC, which is principally to destroy the mantle of impunity shielding Duterte from any criminal accountability and responsibility for his crimes against humanity.

It is imperative that the victims’ own narrative becomes mainstream. It is inevitable that the victims’ articulation of their own experiences and struggles for seeking justice assumes political importance. Their very own articulation of their narratives partakes of the nature of a political act. Their powerful voice will help to undermine the elitist mindset that justifies and perpetuates the arbitrary and summary execution of alleged criminals, lawyers handling drug-related cases, human rights lawyers, and other human rights and environmental defenders.

It is crucial, therefore, for victims to go beyond the four walls of the ICC in advocating for international criminal justice. The victims will need to work with civil society organizations, the media, and progressive church and religious sectors. Inevitably, since their advocacy is for criminal prosecution and justice, their own safety and well-being could very well be at risk. Hence, CSOs will also need to assume frontline roles in articulating their quest for international criminal justice.

In fine, these two emergent scenarios – victim empowerment and ICC investigation as a counter-force to Duterte’s kill orders and state policy of widespread and systematic murder of civilians – form the historic wave that can potentially exorcise Duterte’s vicious legacy of mass atrocities.

About the writer:

Perfecto Caparas is pursuing his Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) studies at Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law. He holds a Master of Laws (LL.M.) in American Law for Foreign Lawyers degree from IU McKinney and an LL.M. in Human Rights degree from the University of Hong Kong (Honors). He is a licensed attorney and lifetime member of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines. He writes regularly for Pressenza and Pinoy Publiko. And, served as a journalist of The Manila Times, Ang Pahayagang Malaya, The Philippine Post, Pinoy Gazette, UCANews, and ISYU Newsmagazine.

Perfecto Caparas is pursuing his Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) studies at Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law. He holds a Master of Laws (LL.M.) in American Law for Foreign Lawyers degree from IU McKinney and an LL.M. in Human Rights degree from the University of Hong Kong (Honors). He is a licensed attorney and lifetime member of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines. He writes regularly for Pressenza and Pinoy Publiko. And, served as a journalist of The Manila Times, Ang Pahayagang Malaya, The Philippine Post, Pinoy Gazette, UCANews, and ISYU Newsmagazine.

The article was first published in: https://www.jurist.org/commentary/2021/10/perfecto-caparas-icc-philippines-politics-mass-murder/

Suggested citation: Perfecto Caparas, International Criminal Court’s Investigation into Philippines’ Politics of Mass Murder, JURIST – Professional Commentary, October 14, 2021,