By Ramu Damodaran

The writer is Chief, United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI) hosted in the Department of Global Communications. This OpEd first appeared in the #WhyWeCare, @ImpactUN on February 5.

“Nostalgia for the present“ is a phrase I once heard (or think I have), and it came to mind when reading a response received to last week’s (January 29) column and its looking back on CTAUN’s quarter-century of affirmation and affection. The question asked was straightforward; had CTAUN (Committee on Teaching) been able to “convene” over the past year? The answer, which I missed noting in my nostalgia for the past, is yes…three times actually.

The first, physically at the United Nations, in its annual conference with the theme “War No More”, on February 28, a web conference choreographed by Elisabeth Shuman on media literacy on December 8 and then one curated by Mary Metzger, on the United Nations and Indigenous People on January 24, International Day of Education.

Among the galaxy of participants, Mary brought to the event was Wilton Littlechild, the Cree lawyer and humanist who served in Canada as Grand Chief of the Confederacy of Treaty Six First Nations, as member of Parliament, and on the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

In that last context, he has spoken about looking at reconciliation “from two different places. One is from a cultural perspective. In my language, in Cree, when you say “reconciliation” it’s called Miyowahkotowin. It means “having good relations.” That’s what reconciliation is in my view, and I have a cultural support for that in our ceremonies, where we have protocol: Waypinasun, which can mean “letting go” when it is offered in that spirit. Whether it’s letting go of a bad experience to find a place where you can forgive, or, once you’ve let go, regaining your own self, your strength as an individual so you can start to get back to the balance that you were first blessed with.”

That regaining of self and identity is central to the individuality upon which the United Nations Charter is based (its reference to the “dignity and worth of the human person” and not “of human people” in particular.)

As this column recalled some months ago, it was as recently as 2007 that the United Nations adopted its Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, implicitly central to which was what an academic paper by the International Labour Organization two years earlier described as the “right to be different.”

That was a right whose horrific extinction was manifest in the Holocaust, whose remembrance and commemoration we observed last week. As Professor Xu Xin, Professor and Director of the Centre of Jewish Studies, Nanjing University (People’s Republic of China) has written “what Hitler did is considered as a crime against humanity. It raises a number of questions concerning mankind.

For instance, how could a group of human beings (the Nazis) do such evil things to another group (the Jews)? Why did the rest of the world stand by in silence while the Holocaust took place? What is human nature? What happened to the sense of human rights during the Second World War?”

Dr. Xu’s observations are included in his contribution to the first in a discussion papers journal series published by the Holocaust and the United Nations Outreach Programme, established by the General Assembly in 2005, which its founding Chief, Kimberly Mann, developed into one of “remembrance and beyond”, one which Rabbi Arthur Schneier, Senior Rabbi at New York’s Park East Synagogue, and the Founder and President of the Appeal of Conscience Foundation, in an article in the UN Chronicle, described as having “awakened people across the globe to humankind’s ability to do evil – but also to our capacity to take action to repair our world…a permanent and potent program of education (going) beyond memorializing; it would serve as an antidote to Holocaust denial, a vaccine to prevent the virus of anti-Semitism and racism from ravaging future victims.”

Those attributes are in many a sense the founding stones of the United Nations; as António Guterres has written in his foreword to the United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech, we have “ a long history of mobilizing the world against hatred of all kinds through wide-ranging action to defend human rights and advance the rule of law. Indeed, the very identity and establishment of the Organization are rooted in the nightmare that ensues when virulent hatred is left unopposed for too long.”

Reading the Secretary-General, my mind went back to an essay on Fascism by the late Professor David Ingersoll, Professor Emeritus at the University of Delaware (where US President Joe Biden was among his students) where he argues “perhaps most fundamentally – especially from the perspective of liberal modernity – fascism does not believe that the human being is expressing its most valued, living potential when it uses its capacity to reason for the purposes of individual and collective human enlightenment. Fascism is hostile to reason and “intellectual” reflection. This is one of the main reasons fascism is associated with action and not ideas.”

The Holocaust and the United Nations Outreach Programme has sought to build upon the power of ideas, which fascism suppressed and which the United Nations and Holocaust education have sought to animate, to create the power of action. Speaking at an event at the United Nations five years ago as part of the programme, Professor Zehavit Gross, Chairholder, UNESCO Chair in Education for Human Values, Tolerance and Peace, School of Education, Bar- Ilan University, noted we were “honoured to live in one of the most splendid periods in human history. We live in a world of advanced technology, knowledge, and material richness and the question is what are we doing with it? Have we learnt to live in peace with each other? Have we learnt to respect difference and the human rights of others? If we look around the world today, we can see huge challenges. With all our technology we have not learnt to overcome evil. Yet, it is our responsibility to work for a better world. And the Holocaust must, through education, become a powerful tool against racism, helping to educate towards a better, more just, cosmopolitan future for the benefit of all humanity.”

The span of 2020 was bookended by two events manifesting “remembrance and beyond” in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. A year ago, the city was host to an exhibition created in partnership with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum “Some were neighbours: choice, human behaviour and the Holocaust”, which reflected on what people did – or didn´t do – during the Second World War, in ways that helped the victims – or did not, by contributing to the rise of antisemitism and Nazism.

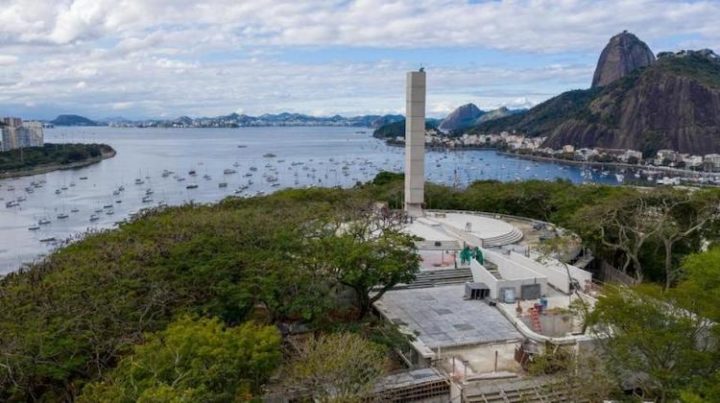

And on December 14 Rio inaugurated a Holocaust memorial, pictured above, that includes a 72-foot-tall tower and overlooks Sugarloaf Mountain, at the mouth of Guanabara Bay, whose name has indigenous origins in the Tupi language, goanã-pará, from gwa “bay” with nã “similar to” and ba’ra “sea”, allowing its ready translation to “the bosom of sea”.

That image brought to mind the call by Secretary-General Guterres on February 3, in his message for the launch of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, for “knowledge – an ocean science revolution…restoring the ocean’s ability to nurture humanity.”

The ocean, in that tidal phrase, could well be a metaphor for education, the revolution seen within it by innovation and exploration, like that relating to the Holocaust, and education as a means to “nurture humanity” within its bosom, a bosom as nurturing and secure as that of the sea, an education which respects the lesson, no, the warning, of history, as António Guterres phrased it in his address to the German Bundestag in December, “that politics driven by anger, distortion and scapegoating is always – always – a recipe for disaster.“

A reflection of what the legendary scholar Professor Yehuda Bauer Academic Adviser to Yad Vashem – The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority (Israel) wrote in the very first discussion papers journal, that “politics that are not based on moral basis are, at the end of the day, not practical politics at all.”

Dr. Bauer had himself addressed the Bundestag twenty years ago, where he said: “I come from a people that gave the Ten Commandments to the world. Let us agree that we need three more commandments, and they are these: thou shalt not be a perpetrator; thou shalt not be a victim; and thou shalt never, but never, be a bystander.”

Those words echoed in mind as I read Rabbi Schneier’s article in the Chronicle cited earlier, and his reference “to borrow from an old show tune, “You’ve got to be taught”. And what we must teach are respect, civility, the foundational values of justice and freedom – in short, to “love your neighbour as yourself”.

Reading those stirring lines, and wishing circumstances allowed us to hear them in Rabbi Schneier’s own voice of gentleness and steel, I thought of another tune and song of hope triumphing memory, of learning, that can be, like regret, lifelong.

Teach your children well

Their father’s hell did slowly go by

And feed them on your dreams

The one they pick’s the one you’ll know by

And you of tender years

Can’t know the fears

That your elders grew by

And so, please help

Them with your youth

They seek the truth

Before they can die

Photo: Memorial to the Victims of the Holocaust, Rio de Janeiro. Credit: UN Academic Impact