By Jhon Sánchez

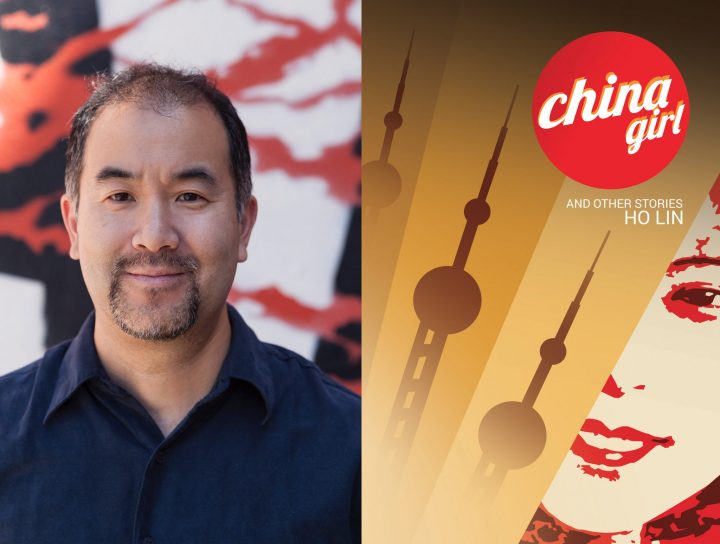

In 2017, Ho Lin edited one of my short stories, but we met in person for the first time in February 2018, during a reading of his book, China Girl, at Bluestockings in New York City’s Bohemian Lower East Side neighborhood of New York City. In November this year, Ho Lin returned to New York, this time as a guest speaker for a class I teach at Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC). He came all the way from San Francisco, where he lives and edits Caveat Lector, a literary journal.

After the class we grabbed some pizza and talked about movies and literature. Ho Lin is also a filmmaker and musician, and many of his writings can be seen as a conversation between film and music. It would’ve been nice to catch a movie together, but we didn’t have time on this occasion. Maybe next time.

J.S/You were born in the USA, but lived in China for a while, and I think that experience has a direct impact on your book. How did the experience of connecting with your ancestry affect you as a person? Did this collection of short stories begin to take shape here or in China?

After I finished graduate school I lived in China and Taiwan for four years in the late ’90s. The experience opened me up not only to my heritage, but to different ways of telling stories. As an Asian-American growing up in upstate New York, you definitely understand that there is a sense of “otherness” about you. Living in Asia took me to the other end of the scale, where people assume you’re a foreigner because you don’t look or act like a “local.” And while there are challenges being in that uncertain, fluid space between cultures, I came to find that there were also opportunities to play around within that space, creating stories set in (or inspired by) Asia that have a multicultural perspective.

Not every story I write has an Asian connection, but when I started putting China Girl together, I noticed that many of my stories had these commonalities, and it is these pieces that ended up in this collection. The first (and earliest) story in the collection, “China Girl,” was inspired by people I knew in China, and written around 2002, and the most recent story, “National Holiday,” was written in 2016.

J.S/ Besides the topic, one of the characteristics of your collection is the constant playfulness with the structure. The stories are told in a non-traditional way. You challenge the story telling process. Have you written stories in a more traditional way? How did you transform your storytelling into a more experimental form and why?

I think my experimentation dates back to my college days, when I had the fortune of taking a hypertext workshop with the writer Robert Coover. Until that point I was very traditional in my storytelling, but hypertext—or at least, how hypertext was envisioned in that workshop—lends itself to a freer approach, where you can mix different voices, different kinds of media, and even criss-cross stories with other authors. The idea that you can play around with the form of the content appealed to me. And isn’t that more or less how we live life these days? Memories and fantasies and the present are always colliding. One minute we’re very present with what we’re doing, and the next we might be mulling over something from the past, or a piece of music, or a scene from a movie. You could say the way we live now, with so many stimuli coming from all directions, was anticipated by hypertext. It’s certainly informed my work.

Don’t get me wrong, I love traditional stories as well and I always aspire to write more of them. Few things give me as much pleasure as reading a well-written piece of genre fiction. I wish I were better at it, myself!

J.S/ There are two stories told like screenplays. Reading screenplays are difficult but in this case, the stories are fun. What’s is the key for achieving that? Do you think is voice? While reading these stories, I felt like a friend was narrating a movie from beginning to end.

If that’s the impression you had while reading those stories, then I’m pleased, because that’s what I was aiming for. The two stories you’re referring to, “Floating World,” and “Trio,” are labelled as “film treatments,” but they’re not treatments in the literal sense. Any Hollywood exec would tell you they fail to fulfill the goal of a treatment, which is to provide a complete explication of the story. When I was putting these stories together, I thought of them in terms of emotions—what kind of feelings did I want them to elicit?

These days, so many screenplays spell out everything about the story. From a certain standpoint, you have to, because a screenplay is supposed to be a “roadmap” for a film production. With these stories, I went the other way and approached them as open-ended questions rather than complete statements. I give you a scenario, I describe characters, I present plot movements—but much of what happens in these stories is unsaid, or left to the reader’s imagination. Hopefully that inspires the reader to fill in some of those blanks, and gives you the feeling of possibility. You could say it’s a trick, because I’m presenting it in a format that leads you to think everything will be explained to you, but I wanted to capture that sense of ineffable magic that all good films have. Part of that magic is the connections that a viewer makes with a movie as the viewer “interacts” with it, so I tried to preserve that by leaving these stories open enough for the reader to engage with them.

J.S/ In “National Holiday,” you named one of your characters “Little Prince.” This immediately made me think of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s classic book of the same title. The story also has a language, ambience and a journey that resemblance “The Little Prince.” It has a fable-like touch but within a certain political context. It’s a story that talks about censorship. Could you comment on that?

I had a stimulating chat with David Andersson on his program “Face 2 Face” a few months ago, which centered mostly on China’s development. David was very bullish on China, and considered it to be more advanced than the US at the present time, in terms of growth and efficiency. I can’t necessarily disagree given current trends in U.S. politics, but I also think that in celebrating China’s achievements, there’s a danger of overlooking its very real issues of censorship and authoritarianism. When independent Hong Kong book publishers who print unflattering books about Chinese politics suddenly “disappear” for months, are finally declared to be in custody, and forced to shut down their businesses, it tells me that censorship is still alive and well in China. You could argue that censorship is also very present in America, and I would agree—for me, it’s a case of different stripes but same animal.

At the same time, it has been noted—accurately, I think—that the current Chinese regime is probably the most benevolent the nation has had in its long history. That might say more about Chinese history than about the current regime, but nevertheless, I acknowledge the gargantuan task China faces. I think Bette Bao Lord once said that when you’re dealing with over a billion people, the ruling hands cannot be too soft.

That’s a long-winded explanation, but it forms the backbone of “National Holiday,” where two opposing viewpoints collide with each other. “The Little Prince” is a young rising Party member who is a pragmatist—he understands that not everything his government does is necessarily fair, but he also believes that it’s impossible to make progress and accommodate everyone. In the story, the Little Prince has to “babysit” a rogue journalist who writes uncomfortable things about government and society, and prevent him from making any controversial statements during the celebration of the current regime’s birth. Such situations actually happen with activists in China. In my story, no one’s mind is necessarily changed, but the two men do come to a sort of understanding of each other, which you could read as an inverted version of Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. (Incidentally, I love Saint-Exupéry’s work, especially his autobiographical writings on air travel).

With “National Holiday,” I tried to give a true-to-life situation a fable-like quality, but without a pat conclusion. Nobody gets a happy ending, but life goes on, everyone gains a little wisdom, and possibilities still exist—which is also similar to Saint-Exupéry, I suppose.

J.S/ As I told you the day I met you, I love the title China Girl. It says a lot about the book and reminds us of one of David Bowie’s songs. In Spanish China is feminine so the emphasis of China as a woman is just beautiful. Could tell us what is for you the deeper meaning of the title? Is the title a metaphor for how we, in the West, see China?

Just the term “China Girl” is pretty loaded. On a recent visit to China, I was often asked who the “China Girl” in my book was! The simple answer is that the main character in the story “China Girl” represents the modern Chinese woman—smart, ambitious, wanting to break out, very aware of the obstacles her society and nationality has placed before her. But it’s also about how other people see her, which is where the David Bowie song comes in. We have notions in the West about what Chinese women (and Asian women) are like, and these notions can be limiting. That comes through in Bowie’s song, which is directly referenced in the story.

I do think that on the whole, women are more interesting than men. They have a self-consciousness and awareness of the world around them that a lot of men don’t have, and it’s a challenge for me as an author to explore that. In “China Girl” I tried to present a realistic portrait of an everyday woman in China. There’s a sadness in her situation, but also moments of connection and joy. For me, it sums up what China is about—it’s not an easy place to live, but it has a certain energy and rhythm unlike anywhere else, and I feel that comes through most powerfully through its women.

J.S/ The United States has lived through shameful moments of discrimination, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, which was born out of negative perceptions about Chinese immigrants. Now, we’re experiencing a new wave of discrimination, mostly against Mexicans and Muslims. What are the lessons that Chinese learned from this dark period? Do the Chinese support other minorities who experience discrimination? Or is there a disconnection among the different groups? Can we bridge that disconnection? What’s the role of writers in achieving this goal?

Very heavy and important questions. One thing the Chinese people have is a ton of patience. You have to, in order to put up with what they’ve had to put up with in history. They made do for decades despite the exclusionary laws against them in the US, and when the laws changed, they adapted accordingly. On the other hand, I think Chinese people are pragmatic by nature, so their instinct is not to rock the boat. While I believe they are naturally sympathetic to the plights of other minorities, they will always be cautious about getting involved. There are always exceptions—the Chinese-American author Frank Chin has been an outspoken ally of Japanese-Americans who were interned during World War II, for example.

The fact is, humans have always found reasons to separate themselves into groups: haves and have-nots, acceptable and unacceptable. We hold the US up as a beacon of freedom and multiculturalism, but it’s no different here. Asian immigrants, Native Americans, black people, certain European immigrants, and now Mexicans and Muslims. I do see change, though. Something like Trump’s wall might have been accepted as a matter of course over a century ago, but now you have dialogue and opposition on the topic. African-Americans might have a long way to go with civil rights, but more voices are being heard on the subject. And as authors, I think as long as we’re bringing out all these viewpoints and voices, we’ll be contributing to debate, and change. Fortunately, I think getting different voices out there is one of a writer’s primary jobs anyway!

J.S/ One of the most emotionally devastating stories in your collection is “Litany, Eulogy.” The opening sentence is “We did not want to attract attention”, but the narrator confronts her father to recount, relive, and call attention to a massacre he had survived when he as child. Why is important to remember painful moments like this one?

It’s funny, “Litany, Eulogy” is dedicated to and inspired by Iris Chang, the author of The Rape of Nanking, and in earlier versions of the story, there was less focus on the narrator’s family drama and more on the wartime atrocities she researches. But even back then, I was grappling with the idea of how dealing with these horrors takes a toll on the person who reports them. This was shortly after Iris Chang committed suicide, and while “Litany, Eulogy” isn’t a depiction of her life, it was meant to dig into the psyche of someone who did what she did for a living.

It wasn’t until a friend of mine misread the story and thought the narrator’s father actually witnessed these tragedies that I realized that I could combine the political and the personal. It adds to the narrator’s sense of guilt that she forces her father to remember these moments, and it makes the story more intimate. She’s recounting historical events, but also events that have directly impacted her upbringing, and even her obsessions. Once it gets to that personal level, you no longer need to go through a laundry list of atrocities—instead you focus on people’s reactions, which turned out to be more powerful.

In the end, the narrator feels like she has a mission, like Iris Chang did, like many of us do as authors, to report on these atrocities. We may be doomed to repeat the past, but if it’s documented and remembered, you at least have a fighting chance to avoid the same mistakes. A life is a story, and the more stories we tell, the more we can understand and document life.

J.S/ I also came from a country that lived a history of violence. Now, in Colombia, we are talking about restorative justice. How is story telling part of the healing process?

There are certain types of justice—the type you find in law courts, or in the social sphere, where someone’s image can be rehabilitated or ruined. The act of telling a story is a different form of justice. You’re giving a voice to experiences—what has happened, or what could happen. Writing can be an act of resistance: This is entering the public memory, where it will not be easily erased or forgotten. Other forms of justice might be subverted, but it’s harder to take away the power of a story. The pen might not always be mightier than the sword, but the words from one pen can reach millions. That’s not something to take lightly.

J.S/ You’re also a filmmaker. You incorporate movies into your stories, the dialogue and the scenery. Can you tell us more about your career as a filmmaker, and how you use movies as part of your narrative?

I don’t consider myself as a master filmmaker by any stretch—I’ve worked on some short projects and a feature-length project that will probably never see distribution—but I enjoy playing around in the medium. I think it’s fair to say that films are the lingua franca of our time, for good and bad. Like books, films are cultural reference points, and indicators of one’s taste.

As a writer, it’s easy to fall into the trap of “cinematic” writing, which mainly relies on describing what’s happening as if you’re watching it in a movie. The vocabulary of film—the visuals, the audio—can be very easily transposed to literature, and that style of writing is very prevalent these days. We also live in a very self-aware time, in which we think about our experiences as if we’re watching a movie. A waiter in New York isn’t just living life; he’s starring in a self-produced movie about his life called “Waiter.” With social media, we’re creating multimedia productions about our lives, every day.

What interests me about film is that it is a very artificial medium—you know what you’re watching on screen is manufactured, unreal—but it still brings out very pure emotional responses. It can also be a prosaic or abstract medium, depending on how you deploy it. I try to accomplish the same in my writing, and by bringing movies into it, whether it’s a film reference or parallel, or the way I structure the story like a film treatment, I pay tribute to the ubiquity of film, while hopefully adding a little twist in this more literary context.

Literature can do certain things that are harder to accomplish in film: describing internal states of being, for example, or introducing a character in a concise manner that doesn’t require clunky exposition or explanatory dialogue. I try to marry the best advantages of both formats in some of my writing.

Naturally I’ve also worked on some full-length screenplays—maybe someday I’ll actually be able to make a movie out of one of them!

J.S/ Tell us about your work as an editor and how this contributes to your creative work.

For me, being an editor is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, I enjoy editing others’ work, and as a co-editor of a literature journal, it’s a great pleasure to find writers and help get their work out. Just the act of reading is like being an editor—even if you’re reading a bad story, you can gain inspiration and ideas. I would have done this part differently. Or: This gives me an idea for my own story.

On the other hand, it can be easy to fall into certain patterns as an editor, just as it’s easy to fall into a rut as a writer. There’s nothing more deadly than having same-ness invade your writing. So I try to apply my editorial eye judiciously to my own writing—enough for me to detect major mistakes, but not so much that I’m prevented from being experimental, or taking chances.

J.S/ The collection is dedicated to your mother, Alice P. Lin. Can you tell us about her and her influence in your life?

My mom loved books. She was a voracious reader and even translated Western novels, such as J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, into Chinese. She had a successful career as a consultant, but she liked to write, and eventually published two books of her own. She was reading mysteries when she was pregnant with me, and I firmly believe my love of mysteries (and literature in general) comes from her.

After she passed away a few years ago, I came into possession of hundreds of pages of her travel writings, dating back to her first visits to China in the late ’70s. Like many from China, her family fled to Taiwan when the Communists took power, so her journals from her China trips are fascinating, both as a glimpse of China before modernization took place, and as a personal story as she reconnected with family and friends she hadn’t seen in three decades. The political married with the personal, once again. I’m in the middle of editing these travel writings, which cover four decades, and hope to get them published in some form soon.

J.S/ I know you’re writing a novel. Can you tell more about that?

My novel elaborates a bit on one of the stories in China Girl, “Ghost Wife,” which mentions the tradition of taking a ghost bride. It’s been documented that in older times, if you were a well-to-do family with a son who died prematurely, you could “hire” a woman to become a bride for the dead son, so he wouldn’t be alone in the after-life. The woman would come live with the family and get all the support and respect one would give a real widow, with the understanding that she would be “married” to the dead son for life. The book I’m working on is contemporary, but pivots on this practice—or rather, an updated version of it. Without giving too much away, the story concerns two friends in Shanghai who go in different directions, and a mystery that leads from the center of urban China to an isolated village in a rural China poised on the edge of modernity.

J.S/ Thank you for visiting my class in New York. Next time, we’ll go to the movies in San Francisco.

Absolutely! Thank you.

Ho Lin is an author, musician and filmmaker, and the co-editor of the literary journal Caveat Lector. He currently resides in San Francisco. www.holinauthor.com

Jhon Sánchez: A native of Colombia, Mr. Sánchez arrived to the United States seeking political asylum. Currently, a New York attorney, he’s a JD/MFA graduate. His most recent short stories published in 2018 are Pleasurable Death available on The Meadow, The I-V Therapy Coffee Shop of the 21st Century available on Bewildering Stories and “‘My Love, Ana,’—Tommy” available on www.fictionontheweb.co.uk