By Shane Burley June 27, 2018

It was about 3:30 a.m. on the morning of Monday, June 25 when armed Federal Protective Service officers returned to the Portland, Oregon office for Immigration and Customs Enforcement. ICE personnel had not been back since June 19, when protesters began disallowing easy access in and out of the building. A mass of people had formed the night before and began blocking the exit at closing time on Monday afternoon.

As the protest ramped up that evening, an ICE staff person came out and demanded the protesters move so that the ICE staff could “go home to their families.” It was that line that caused an insurgent uproar, cementing the creation of a community that included hundreds of people and tents.

Family concentration camps

The Trump administration’s “no tolerance” policy on undocumented immigration, and the revelations that families are being broken up and children placed into cages in detention facilities, has created a vitriolic wave of anger across the country. Protests exploded in dozens of cities, targeting ICE operations who many allege have created a system of terror and oppression for people of color and immigrants. Stories about sexual assault in ICE facilities, the use of forced labor in camps, and the “losing” of children in custody have made this an issue so divisive that the public has been forced to confront it.

While the movement has hit a fever pitch in affected communities in every pocket of the United States, the protests hit a tipping point in Portland, Oregon. A local organization, the Direct Action Alliance, held a rally at the local ICE facility in the city, nestled near a track of high-priced condos newly built along the Willamette River waterfront. That first action pushed for an occupation, a blockade that would directly contest ICE’s ability to continue aggressive immigration arrests, and the growing numbers of protesters decided to enact a round-the-clock vigil.

“The feeling has been one of community and defiance and revolution. It really felt like once the occupation started, and started growing, that we were on to something here,” said organizer Jenny Nickolaus.

A community quickly formed, built on the principles of direct democracy and anti-hierarchical decision making. In the model of the Occupy Wall Street movement, the tent city included a fully functioning kitchen, medical and mental health tents, an accessibility area, childcare and a growing complex infrastructure meant to sustain more than just the protest. Committees and working groups were formed with an eye on maintaining the simultaneous purpose of building relationships and halting the functioning of the building it was quickly engulfing. This was more than just a challenge to ICE, it was a vision of something to replace it with.

Committing to disruption

The Portland occupation sparked a nationwide shift in tactics, moving beyond simple protest and into actions where organizers were committed to the longer-term blockage of ICE functioning in the various administrative and detention centers it operates in.

In New York City, the Metropolitan Anarchist Coordinating Council, or MACC, took the lead on turning a Bikes Against Deportation protest on Thursday, June 21, into a rolling encampment to challenge ICE operations in Lower Manhattan. As the protests continued well into early Friday morning, and confronted an ICE van trying to enter the 201 Varick Street entrance, it was clear that a continuous blockade was starting to form. They had taken over two city blocks by Sunday and were operating in shifts with 20 to 30 people at a time to maintain coverage on the entrance to the facility. While police came and hosed off chalked messages about ICE overreach, ICE canceled all immigration hearings in the building that were scheduled for June 25.

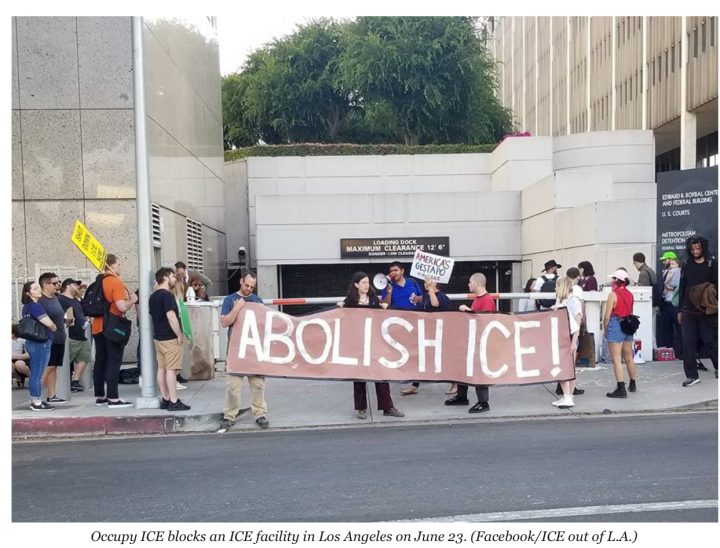

The ICE Out of L.A. coalition, along with groups like L.A. Against ICE and Ground Game L.A., started with a protest action at the Metropolitan Detention Center, which is used by the LAPD, federal authorities, and ICE for detention of undocumented people. As the protest swelled, organizers wanted something that was more than just symbolic and could actually interfere with the basic functioning of ICE in the Los Angeles area.

“We can cause an actual disruption to the injustice of the system,” said John Motter, an organizer who helped start the encampment with Ground Game L.A. “We want to maintain this as a vigil and a show of solidarity for people incarcerated in the building behind us and around the country.”

“We can cause an actual disruption to the injustice of the system,” said John Motter, an organizer who helped start the encampment with Ground Game L.A. “We want to maintain this as a vigil and a show of solidarity for people incarcerated in the building behind us and around the country.”

The protest continued through the weekend, bringing out dozens to maintain watch and keep the protest going on a continuous basis. Those incarcerated in the building have been flashing their cell lights to communicate with protesters on the outside, building a bond between those facing incarceration and the movement of solidarity on the sidewalk.

“It is bigger than just reuniting families, but fixing the problems with, or abolishing, ICE,” said Motter.

Just down the road, and closer to the Mexico border, Occupy ICE San Diego formed out of a massive coalition of groups, from Redneck Revolts to the Democratic Socialists of America, attempting to disrupt ICE operations in a city known for its border militarization. Using a multi-front approach, organizers hit both the Chula Vista Border Patrol and the Otay ICE location on Saturday, shutting it down for 14 hours before state police came in and started making arrests.

“We are a group of organizations, groups, and regular folks who are committed to standing up for the migrant members of our communities. The violence and trauma that Trump’s ‘zero tolerance’ policy has inflicted on migrant families must stop,” said Yesenia Padilla at the encampment.

Viewed from the White House

As the occupations grew, the Attorney General’s Office doubled down on its “no tolerance” policy while opposition from inside the political ranks mounted. Donald Trump finally announced that he would end the policy of separating families through a temporary executive order rather than a concrete policy.

“Trump’s executive order is not even a bandage on this gaping wound, and continues to allow ICE to inflict violence upon our neighbors, family members and friends,” Padilla said, echoing the growing view that the entire system of immigration in the United States is untenable.

As the protests grew, it was not just the policy of family separation that was brought into focus, but ICE as an institution. Organizers keyed in on the goal of abolishing ICE wholesale, using the language of prison abolition of a way of linking up these movements.

“It is directly connected to our other causes, prison abolition, abolishing the police,” said Kim Kelly, an organizer with MACC in New York. “Every cage is still a cage, no matter what the jailer is wearing.”

In Detroit, occupiers came with a clear goal of shutting down the facility, disrupting the “business as usual” approach to incarceration of undocumented people. Groups had come together with the intention of blockading from the start, and they blocked all three entrances to the Detroit ICE facility for several hours on Monday morning until police swarmed the protesters with threats of pepper spray and zip ties. The group has reconvened and re-establishing the encampment on June 26.

“With 40 people we shut down operations at an ICE facility for six hours. Come out and let’s see what we can do with 400,” said Robert Jay, of Occupy ICE Detroit and the Metro Detroit Political Action Network.

Occupy ICE PDX

On Sunday, June 24, a rally with hundreds of people was held at the Portland City Hall with politicians and community leaders openly calling for the abolition of ICE. Chloe Eudaly, the Portland city councilor who rode into office with the support of tenant rights organizations, came out to the occupation to show her firm support. This has been echoed in some sectors of the Democratic Party, with Wisconsin Rep. Mark Pocan introducing a bill to eliminate ICE.

By mid-morning on June 25, law enforcement had put out an official notice to the Portland encampment indicating that occupiers could face criminal charges. In their public release, which they attempted to hand out to the encampment, they stated that the blocking of areas such as entrances, the creation of loud noise, or anything that “disrupts the performance of official duties by government employees” could be subject to criminal charges.

One organizer, who asked to remain anonymous, said that they were visited by a federal public defender who noted that the Federal Protective Service was planning to evict the camp and possibly seek prosecution of the occupiers on federal statutes.

“I don’t think we have weeks. I think we have days,” the organizer said.

That certainly seemed correct as the pressure mounted on June 25, with police making return visits and occupiers alleging tear gas being fired at them from inside the ICE facility. The Portland encampment is maintaining itself despite threats from law enforcement, including potentially serious federal charges.

“No one has any plans on leaving anytime soon,” said Jordan Sheldon, a member of the Occupy ICE PDX media team. “We will be making sure we keep everything in order to make sure we don’t get swept.”

With the encampment continuing, they are calling for the city to do what it takes to become a “true sanctuary city” and to disallow ICE operations. This is part of the larger push to dismantle the system of mass immigrant incarceration that Trump and Jeff Sessions are expanding, and to see abolition and community as the answer to this policy. If the occupations are able to multiply, grow and withstand state intervention, the large scale demands of abolition — rather than the incremental reforms offered by politicians — will continue to gain traction.