By Jhon Sánchez

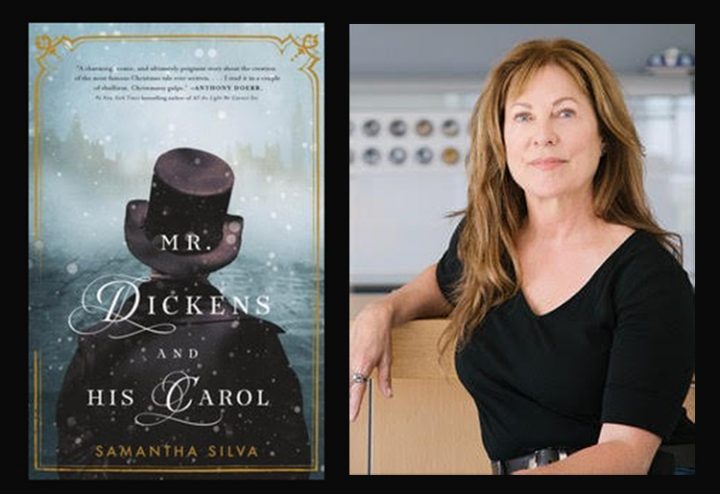

The last time I read “A Christmas Carol” was in April of this year. I assigned a graphic novel of the book to my students to study character arc. Like most children from my generation in Colombia—and the generations before, I grew up, reading, watching or listening to A Christmas Carol. I have seen so many adaptations of the story, and it has never ceased to fascinate me. Charles Dickens was for me a shadow someone probably like Scrooge but sometimes I pictured him as Tiny Tim; I had a blurry vision of Dickens’ life, his struggles to write but once I read “Mr. Dickens and his Carol” by Samantha Silva, I heard Charles Dickens whispering to me: Merry Christmas.

Samantha, thank you for this gift, this Christmas gift to all of us, to all of us who had read ‘A Christmas Carol’ and who love Charles Dickens.

- I said that I heard Charles Dickens whispering to me because it’s true. It happens to all books I love, but I should have said that it was you, Samantha, who was whispering to me and only to me. One of your characters while talking about Charles Dickens’s stories says, “[I] found from the very first page of the very first book the strangest sensation that I did know you, and that you know me…” Tell me about your encounter with Charles Dickens and how it inspired you to write this novel.

Thank you, Jhon. I’m glad to know that Dickens whispered to you through the novel. He’s been whispering to me for years, since a friend suggested we write a ghost story anthology movie when she’d heard that’s how Dickens birthed the Carol. But the more I read about its true origins, the better I liked the story – or at least the story possibilities it suggested. I started to read Dickens seriously, and read about Dickens seriously. He got under my skin. During the first few drafts (of what began as a screenplay), it almost felt like he was in the room with me, telling me his secrets, urging me on. I say the book is a fan letter – a love letter – to Dickens, that makes clear how I see him: as a deeply flawed man with a heart as big as the world, who lived with a lot of darkness, inside and out, but leaned, urgently and frantically, always toward the light.

- Charles Dickens says in your book, “The book has rewritten me”. How has your book rewritten you?

That’s a good question, because it’s a hard question. I think writers are always trying to work out some unresolved problem, whether it’s deeply personal or a view of the world. We ache to be resolved. But often we don’t know what that thing is until we put it to paper. The writing of any story has its own arc, a story that’s told back to you, the writer. And because this screenplay-turned-novel has occupied such a long span of my life, I have some narrative distance from my own arc. I think, at the start, I was writing about my own attraction to complicated, intelligent, charismatic men – the love and approval I’ve sought from them. It was almost a wishful fantasy. By the end, I was writing about forgiveness, and compassion. And about my own flaws, and desires.

- Do you believe that, in a way, we writers become the characters we describe, that Charles became Scrooge while he was writing his novel?

If characters are working in the story, doing what they’re supposed to do – propelling the story forward – then I think they will not leave you alone. I’m such a Jungian in that way. If we are all the characters in our own dreams, we must also be all the characters in our stories. Dickens was known to say that his “bad” characters were some exaggerated representation of his own flaws, and that his “good” characters represented the person he aspired to be. And Mr. Dickens turns on the very idea that he could become Scrooge – that put under enough pressure, Dickens might tire of his commitments and responsibilities, and become miserly and heartless himself. But it’s a part of him that’s been there all along. And again, aches to be resolved.

- Besides, Charles Dickens, my favorite character is Eleanor Lovejoy, her demeanor, her sentences, all the mystery that it’s behind her, even the color of her cloak, purple. What was the origin of this character?

Dickens believed in a muse. He thought his first love, Maria Beadnell – who scorned him mercilessly – had been his original muse, and that in some ways her rejection propelled him into his writing life just so he could prove her wrong. But I’ve also been a muse in my life. It’s great work if you can get it, but it also allows an artist to use you as a projection (Jung again), as opposed to seeing your own totality as a person. So, Eleanor begins as a muse, but ends as something else, I hope, something more whole, and more real. As for “Eleanor,” I carry a tiny photo in my wallet of my grandmother with Eleanor Roosevelt. She’s a hero of mine, and I think it one of the noblest names. And “Lovejoy” gets right to the heart of what the book is about.

- I started to read the book and found Charles Dickens like any other writer trying to write a story, struggling to find his muse while under financial pressure. But at the same time I bared in my mind that he was going to succeed. I had different expectations about the plot, but you managed to twist of all them. Were you aware that we would expect something from the plot but you purposely withdrew the carrot? Or did the story naturally evolve in a way that emphasized mystery?

I wish I could say that I’d plotted this out ingeniously, but the story came to me, almost in a fever dream. I woke up one morning, bolted upright in bed, and just knew what it was: beginning, middle, end. There were some delightful discoveries along the way, and I mined all of them as far as I could, but the twists and turns came so naturally, it was almost like following a map. It’s like being in the right place at the right time: if you have the right crisis at the right moment in your character’s life, drama (and comedy) unfold before your very eyes.

- I think anyone can read your story, children of any age, teenagers, adults, retirees. I’m a second language speaker and have found a spice in the language in combination with the images that allowed me to be in London during the year of 1843 or so. How did you study that? Did you use your skills as a screenwriter to bring that flavor? Any advice for us aspiring writers on that point? How do we know we have enough ‘spice’ to be just right?

As a long-time screenwriter, I’m a structuralist, and a minimalist, but because I’d optioned the film rights four times, I knew the bones of the story worked. Adapting it as a novel, and becoming a novelist along the way, was like using the bones to hang some muscle, flesh, and juicy bits of fat. At first I didn’t know how to gauge how much detail, or interior life of the character, was too much, or not enough. But after the first or second draft, I felt it as a kind of freedom, even permission to go down some rabbit holes. I could spend an entire afternoon reading about the lace on the undersleeve of a Victorian dress, or the damask on a chaise. But in the end, you have to pick the best details – be spare with what’s rich – and illuminate a character’s inner landscape with the soft light of a single bulb (or gas lamp).

- You write referring to a magic trick, “Dickens knew the deception well, but he smiled nonetheless, not for the brilliance of its execution—it was on the sloppy end of magic tricks—but for the truth at the bottom of every illusion, every fiction, every lie: our own great desire to believe.” Is this why fiction or art works in us?

Yes, it’s exactly why. It’s that ‘suspension of disbelief’ that happens every time we open a book, walk into a theater, or when the lights go down in a movie house. We want to be taken outside of ourselves, sometimes just for sheer distraction and entertainment, but often so that we have some narrative distance from our own lives, so we can look back at ourselves – our desires, needs, realities, hardships, and blessings, reflected back to us. It’s almost an aspiration: The more I can get you to be swept away by Dickens’ life, the more you’ll be enthralled by your own. But it’s a big responsibility for a writer, it must be earned. I hope I have.

- Another quote, “A made up name could hold a truth, even if [Dickens] didn’t know what truth it yet was.” Is that they way we build characters?

Dickens was a master of making up names – an onomastic genius. No one can touch him. Eleanor Lovejoy is a small nod to his brilliance, but I do think, if we don’t possess that special genius, there’s still a way of attaching names to characters, and people we’ve known or met to characters we’re creating (which is exactly what Dickens did), to aid us along the way. Having someone in mind, I think, makes the mind sharper. But I confess I keep an ongoing list of names I love that must someday find their way into my writing; to wit, I once passed a highway sign for an exit that led to two towns: Zillah Toppenish. Doesn’t a name like that demand a whole novel, if not a trilogy?

- This is a work of fiction. Were you tempted to write something more autobiographical or struggle between the two possibilities until the fiction took over.

Around the dinner table, when my kids were young, we created a game where, if anyone told a story, you got to shout out whether it was a short story, a novel, a movie or play. And you were basically calling ‘dibs’ on it. I go through my life like that. I see the fictional possibilities in almost every good, true story. But I hate to be constrained by the facts. Fiction lets you explore the outer reaches of the human experience. But when it’s grounded in real things, all the better.

- Let’s imagine for a moment that in two hundred years someone is writing about you, Samantha Silva. They’ve read your biography, the things you have written, your personal diary, they have looked at your pictures, they may have a tuft of your hair. What part of your daily routine would you like to be included in that book? Any personal Christmas stories?

I would like them not to mention that sometimes I play word games on my phone to distract me from the work at hand. And that I hate the commercialism of Christmas. But they could say that I love the gathering around the hearth. It took my siblings and I years to convince our mother that we should all stop spending money on things people didn’t need, which is when she came up, in retaliation, with the idea of ‘the Christmas letter’ that all five of us kids (and various parents and step-parents), were to write, to be read aloud on Christmas morning, saying anything we wanted about the year behind us. We all complained about it for weeks before the deadline, and usually wrote our letters the night before Christmas, thick with bourbon or spirits of one’s choice. But I have to say, it’s some of the best writing I’ve ever heard. (Thank you, mom.)

Samantha, did you hear that? Or is my imagination? Jingle bells, jingle bells, jingle all the way.

I do hear it. Thank you, Jhon, for hearing it, too.

Samantha Silva is an author and screenwriter. Mr. Dickens and His Carol is her debut novel.

Jhon Sánchez: A native of Colombia, Mr. Sánchez immigrated to the United States seeking political asylum. Currently, a New York attorney, he’s a JD/MFA graduate. His work has been nominated for The Best of the Net 2016 and for a Pushcart Prize in 2015 and 2016. He was also awarded the Newnan Art Rez Program for summer of 2017. More of Mr. Sanchez’s work can be found at Breakwater Review, Newfound, Gemini Magazine, 34thParallel, Foliate Oak Literary Journal, Swamp Ape Review, Sand Hill Review, Midway Journal and more recently in Midway Journal Volume 11 Issue 4